Hal Foster at Artforum:

The wager made by Atkins is that if reality can be derealized by such technologies, it might also be rediscovered there, and this might occur in a few ways. First, he believes that, once outmoded, technology passes over to the side of “base materiality”; its very clunkiness becomes a reality effect. Atkins adapts the term corpsing—the moment when an actor breaks character and so dispels the illusion of the performance—“to describe a kind of structural revelation more generally”; his examples are when a vinyl record jumps or a streaming movie buffers. To corpse a medium is to expose its materiality, even to underscore its mortality, and in this moment the real might poke through. Second, punctuated by the gestural tics of the Atkins avatar, The Worm is also rife with manufactured glitches—sudden blurs, flares, beeps, and crackles—and these apparent cracks in the artifice might provide another opening to the real. Although these reality effects are artificial, “they baffle the signs of reality by parodying them, engendering a new kind of realism.”7 Third, if the real might be felt when an illusion fails, so too might it be sensed when that illusion is “glazed with effects to italicize the artifice,” that is, when illusionism is pushed to a hyperreal point.

The wager made by Atkins is that if reality can be derealized by such technologies, it might also be rediscovered there, and this might occur in a few ways. First, he believes that, once outmoded, technology passes over to the side of “base materiality”; its very clunkiness becomes a reality effect. Atkins adapts the term corpsing—the moment when an actor breaks character and so dispels the illusion of the performance—“to describe a kind of structural revelation more generally”; his examples are when a vinyl record jumps or a streaming movie buffers. To corpse a medium is to expose its materiality, even to underscore its mortality, and in this moment the real might poke through. Second, punctuated by the gestural tics of the Atkins avatar, The Worm is also rife with manufactured glitches—sudden blurs, flares, beeps, and crackles—and these apparent cracks in the artifice might provide another opening to the real. Although these reality effects are artificial, “they baffle the signs of reality by parodying them, engendering a new kind of realism.”7 Third, if the real might be felt when an illusion fails, so too might it be sensed when that illusion is “glazed with effects to italicize the artifice,” that is, when illusionism is pushed to a hyperreal point.

more here.

In a laboratory in Israel, an incubator drum spins on a bench. The two glass bottles attached to the drum contain mouse embryos, each the size of a grain of rice, with translucent, pulsing hearts.

In a laboratory in Israel, an incubator drum spins on a bench. The two glass bottles attached to the drum contain mouse embryos, each the size of a grain of rice, with translucent, pulsing hearts. It can happen here. The “it” ought to be obvious by now: an authoritarian or even fascist regime in the United States. That was a big reason why Harvard professor Steven Levitsky, along with his colleague Daniel Ziblatt, published the 2018 book “

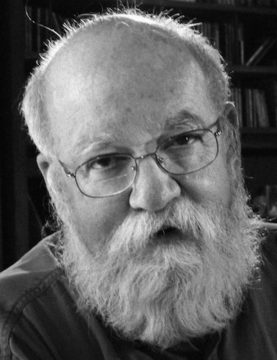

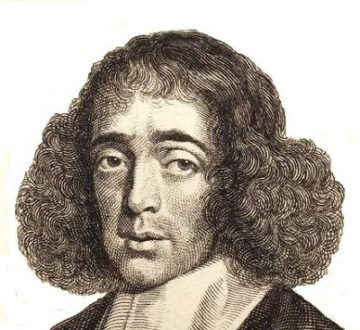

It can happen here. The “it” ought to be obvious by now: an authoritarian or even fascist regime in the United States. That was a big reason why Harvard professor Steven Levitsky, along with his colleague Daniel Ziblatt, published the 2018 book “ Genevieve Lloyd has done much to promote serious engagement with Baruch Spinoza and has demonstrated many ways in which Spinoza can inform and challenge current debates in the philosophical mainstream. In her article in this issue, Lloyd invites us to challenge the simplistic caricature of Spinoza as a paradigm ‘rationalist’, thus providing us with rich insights into the subtleties of Spinoza’s naturalist view on minds, knowledge, and reason. This more accurate picture, however, offers a striking similarity to the work of Daniel Dennett. Indeed, Spinoza and Dennett are alike in sharing their fervent opposition to Descartes’ conception of mind and body.

Genevieve Lloyd has done much to promote serious engagement with Baruch Spinoza and has demonstrated many ways in which Spinoza can inform and challenge current debates in the philosophical mainstream. In her article in this issue, Lloyd invites us to challenge the simplistic caricature of Spinoza as a paradigm ‘rationalist’, thus providing us with rich insights into the subtleties of Spinoza’s naturalist view on minds, knowledge, and reason. This more accurate picture, however, offers a striking similarity to the work of Daniel Dennett. Indeed, Spinoza and Dennett are alike in sharing their fervent opposition to Descartes’ conception of mind and body. Lloyd [2021] herself alludes to Dennett when she suggests that a serious engagement with Spinoza might allow us to provide an alternative framing of the problem of consciousness—one that replaces the current metaphors with what Dennett [1991: 455] would describe as novel ‘tools of thought’. While Lloyd [2017] has addressed the connection between Spinoza and the problem of consciousness in a previous publication, little has been made of the connection between these two Anti-Cartesian conceptions of the mind.

Lloyd [2021] herself alludes to Dennett when she suggests that a serious engagement with Spinoza might allow us to provide an alternative framing of the problem of consciousness—one that replaces the current metaphors with what Dennett [1991: 455] would describe as novel ‘tools of thought’. While Lloyd [2017] has addressed the connection between Spinoza and the problem of consciousness in a previous publication, little has been made of the connection between these two Anti-Cartesian conceptions of the mind. Testimony by former Facebook employee Frances Haugen, who holds a degree from Harvard Business School, and a series in the Wall Street Journal have left many, including

Testimony by former Facebook employee Frances Haugen, who holds a degree from Harvard Business School, and a series in the Wall Street Journal have left many, including  If you are concerned about the well-being of the United States and interested in what the country could do to help itself, stop what you are doing and read historian Geoffrey Kabaservice’s superb 2012 book,

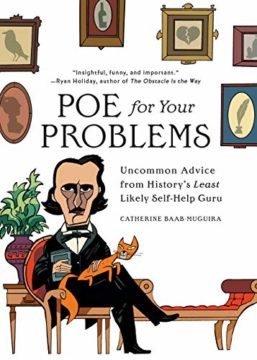

If you are concerned about the well-being of the United States and interested in what the country could do to help itself, stop what you are doing and read historian Geoffrey Kabaservice’s superb 2012 book,  “Live your best life.” It’s one of the most common, yet worthless, aphorisms offered today. Chipper, insipid, and surprisingly relativistic (it fits arsonists as well as anybody), this meaningless maxim is the Tic-Tac of modern aspiration, boasting all the nuance and depth of Target word-art or pastel Instagram posts. Fed up with such drivel, and equally skeptical of the therapy-industrial complex, writer Catherine Baab-Muguira urges us in her debut book of nonfiction to take the exact opposite tack: to live our worst life instead.

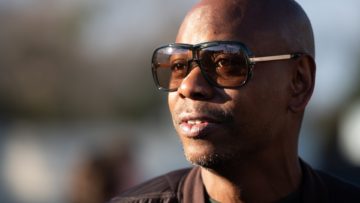

“Live your best life.” It’s one of the most common, yet worthless, aphorisms offered today. Chipper, insipid, and surprisingly relativistic (it fits arsonists as well as anybody), this meaningless maxim is the Tic-Tac of modern aspiration, boasting all the nuance and depth of Target word-art or pastel Instagram posts. Fed up with such drivel, and equally skeptical of the therapy-industrial complex, writer Catherine Baab-Muguira urges us in her debut book of nonfiction to take the exact opposite tack: to live our worst life instead. Towards what seemed like the halfway point of his show in London last night, Dave Chappelle announced to the crowd he was going to tell us something he was refusing to tell the media. He wanted us to know, he said while looking sadly at the floor, that his quarrel was not with the gay or the trans communities . No, no. Looking up and raising an index finger, he explained: ‘I’m fighting a corporate agenda that needs to be addressed.’ Thinking we still had another hour of the show to go, we cheered. ‘You fight those corporate vampires, Dave!’ we thought. He then let us know, whenever it was possible, that we should be kind to one another. Very shortly after that he raised his thumbs aloft and walked off stage: 45 minutes. Friday night tickets are £160. You show those corporate vamp… oh.

Towards what seemed like the halfway point of his show in London last night, Dave Chappelle announced to the crowd he was going to tell us something he was refusing to tell the media. He wanted us to know, he said while looking sadly at the floor, that his quarrel was not with the gay or the trans communities . No, no. Looking up and raising an index finger, he explained: ‘I’m fighting a corporate agenda that needs to be addressed.’ Thinking we still had another hour of the show to go, we cheered. ‘You fight those corporate vampires, Dave!’ we thought. He then let us know, whenever it was possible, that we should be kind to one another. Very shortly after that he raised his thumbs aloft and walked off stage: 45 minutes. Friday night tickets are £160. You show those corporate vamp… oh. C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh in Boston Review ( Image: James Robertson/Jubilee Debt Campaign):

C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh in Boston Review ( Image: James Robertson/Jubilee Debt Campaign): David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele over at CNN:

David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele over at CNN: Sophie Elmhirst in The Guardian (Illustration by Pete Reynolds):

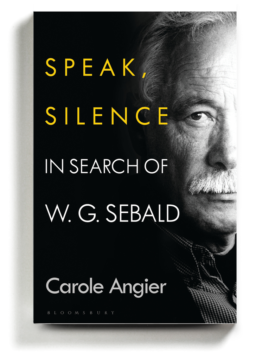

Sophie Elmhirst in The Guardian (Illustration by Pete Reynolds): W.G. Sebald is probably the most revered German writer of the second half of the 20th century. His best-known books — “The Emigrants,” “The Rings of Saturn,” “Austerlitz,” published here between 1997 and 2001 — are famously difficult to categorize.

W.G. Sebald is probably the most revered German writer of the second half of the 20th century. His best-known books — “The Emigrants,” “The Rings of Saturn,” “Austerlitz,” published here between 1997 and 2001 — are famously difficult to categorize. Eliot’s humanism tends to inspire awe in her readers. “She seems to care for people, indiscriminately and in their entirety, as it was once said God did,” wrote Zadie Smith in a 2008 essay on Middlemarch. As it was once said God did. My first thought is of Middlemarch’s omniscient narrator: sage, a little sarcastic, a little judgemental as she tunes into the thoughts of each character, catching them in the act of realising something about themselves.

Eliot’s humanism tends to inspire awe in her readers. “She seems to care for people, indiscriminately and in their entirety, as it was once said God did,” wrote Zadie Smith in a 2008 essay on Middlemarch. As it was once said God did. My first thought is of Middlemarch’s omniscient narrator: sage, a little sarcastic, a little judgemental as she tunes into the thoughts of each character, catching them in the act of realising something about themselves.