Lorraine Boissoneault in Smithsonian:

The pain struck suddenly in Venice.

The pain struck suddenly in Venice.

Writing to her doctor brother-in-law in 1839, famed British writer Harriet Martineau complained of the “inability to stand or walk, aching and weariness of the back, extending down the legs to the heels” and “tenderness and pain, on pressure, in the left groin, extending by the hip to the back.” She’d been traveling through Europe with a group of friends for several months, but now it seemed the completion of her adventures would have to be put on hold.

Within weeks, Martineau was back in England, where she was diagnosed with a retroverted uterus and polypus tumors: two vaguely defined conditions without a cure. (These ailments would likely be diagnosed differently today, but modern scholars often shy away from definitively diagnosing historical figures due to the difficulty of doing so with limited information.) As for treatments, the most Martineau could hope for was iodide of iron for “purifying the blood,” morphine for the pain and the general cure-all treatment of bloodletting. Resigning herself to an illness of unknown duration, Martineau moved to Tynemouth, a town on the northeastern coast of England, and hired nurses and servants to care for her in this new sickroom. She would remain there for the next five years, largely unable to leave due to the pain of walking.

More here.

One day in 2010, when oncologist Paul Muizelaar operated on a patient with glioblastoma—a brain tumor infamous for its deathly toll—he did something shocking. First, he cut the skull open and carved out as much of the tumor as he could. But before he replaced the piece of skull to close the wound, he soaked it in a solution containing Enterobacter aerogenes,1 bacteria found in feces. For the next month, the patient lay in a coma in an intensive care unit battling the bacteria he was infected with—and then one day a scan of his brain no longer showed the distinctive signature of glioblastoma. Instead, it showed an abscess, which, given the situation, Muizelaar deemed a positive development. “A brain abscess can be treated, a glioblastoma cannot,”

One day in 2010, when oncologist Paul Muizelaar operated on a patient with glioblastoma—a brain tumor infamous for its deathly toll—he did something shocking. First, he cut the skull open and carved out as much of the tumor as he could. But before he replaced the piece of skull to close the wound, he soaked it in a solution containing Enterobacter aerogenes,1 bacteria found in feces. For the next month, the patient lay in a coma in an intensive care unit battling the bacteria he was infected with—and then one day a scan of his brain no longer showed the distinctive signature of glioblastoma. Instead, it showed an abscess, which, given the situation, Muizelaar deemed a positive development. “A brain abscess can be treated, a glioblastoma cannot,”  “I’m a storyteller” is a common self-description for virtually everyone in the film industry these days, from directors and scenarists to publicists and marketers. The phrase is a quintessential humble-brag. It carries a sense of modesty: “I may have a profoundly intricate knowledge of my craft, but at heart I’m no different from the people spinning a good yarn for their kids.” But it also holds a whiff of epic continuity, placing the speaker in a line that reaches back to Homer, and beyond that to the nameless bards who first narrativized our species into civilization. All to say: the phrase has passed through ubiquity to become an increasingly mocked cliché. Which is why it was so refreshing to hear the French director Leos Carax say in a recent interview with the

“I’m a storyteller” is a common self-description for virtually everyone in the film industry these days, from directors and scenarists to publicists and marketers. The phrase is a quintessential humble-brag. It carries a sense of modesty: “I may have a profoundly intricate knowledge of my craft, but at heart I’m no different from the people spinning a good yarn for their kids.” But it also holds a whiff of epic continuity, placing the speaker in a line that reaches back to Homer, and beyond that to the nameless bards who first narrativized our species into civilization. All to say: the phrase has passed through ubiquity to become an increasingly mocked cliché. Which is why it was so refreshing to hear the French director Leos Carax say in a recent interview with the  However reductive it may be to call the painter Bob Thompson the Jean-Michel Basquiat of the 1960s, the comparison is inescapable.

However reductive it may be to call the painter Bob Thompson the Jean-Michel Basquiat of the 1960s, the comparison is inescapable. The characters of

The characters of  Otto Celera 500L, it’s one that catches the eye. It looks like no other plane out there, and for a good reason: unique aerodynamics.

Otto Celera 500L, it’s one that catches the eye. It looks like no other plane out there, and for a good reason: unique aerodynamics. Isaiah Berlin understood the parable of the fox and the hedgehog – ‘the fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing’ – to illustrate two styles of thinking. Hedgehogs relate everything to a single vision, a universally applicable organising principle for understanding the world. Foxes, on the other hand, embrace many values and approaches rather than trying to fit everything into an all-encompassing singular vision.

Isaiah Berlin understood the parable of the fox and the hedgehog – ‘the fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing’ – to illustrate two styles of thinking. Hedgehogs relate everything to a single vision, a universally applicable organising principle for understanding the world. Foxes, on the other hand, embrace many values and approaches rather than trying to fit everything into an all-encompassing singular vision. What is it about Poe that grips the popular imagination so, like the medieval Iron Shroud shrinking inward and threatening to crush the narrator of

What is it about Poe that grips the popular imagination so, like the medieval Iron Shroud shrinking inward and threatening to crush the narrator of  Standing in the middle of a room previously inhabited by a now-absent figure can conjure an eerily potent atmosphere, traceable through sensations rather than words. Perhaps it’s because so much of what shapes the edges of any individual’s persona resides within the colors they prefer, their cooking and cleaning smells, or the sounds they regularly hear emanating from the pipes in their walls or a creak in their floorboards. When a person’s body exits their habitat, all the things that previously swirled in and around their tangible body remain, suspended in the air in a thick, viscous hum. These remnants permeate the objects the person leaves behind, too, charged with energy, appearing as sentient creatures rather than a lifeless pile of stuff.

Standing in the middle of a room previously inhabited by a now-absent figure can conjure an eerily potent atmosphere, traceable through sensations rather than words. Perhaps it’s because so much of what shapes the edges of any individual’s persona resides within the colors they prefer, their cooking and cleaning smells, or the sounds they regularly hear emanating from the pipes in their walls or a creak in their floorboards. When a person’s body exits their habitat, all the things that previously swirled in and around their tangible body remain, suspended in the air in a thick, viscous hum. These remnants permeate the objects the person leaves behind, too, charged with energy, appearing as sentient creatures rather than a lifeless pile of stuff. Moments of sociopolitical tumult have a way of generating all-encompassing explanatory histories. These chronicles either indulge a sense of decline or applaud our advances. The appetite for such stories seems indiscriminate—tales of deterioration and tales of improvement are frequently consumed by the same people. Two of Bill Gates’s favorite soup-to-nuts books of the past decade, for example, are Steven Pinker’s “

Moments of sociopolitical tumult have a way of generating all-encompassing explanatory histories. These chronicles either indulge a sense of decline or applaud our advances. The appetite for such stories seems indiscriminate—tales of deterioration and tales of improvement are frequently consumed by the same people. Two of Bill Gates’s favorite soup-to-nuts books of the past decade, for example, are Steven Pinker’s “ T

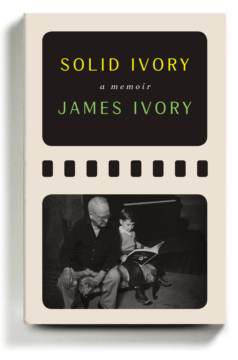

T Merchant and Ivory, normally working with the writer Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, were one of the most dominant cinematic forces of the late 20th century, rolling out luxuriously appointed adaptations of E.M. Forster and Henry James novels, with the occasional more contemporary anomaly like Tama Janowitz’s “Slaves of New York.” Merchant died in 2005; Jhabvala in 2013. After decades conjuring the Anglo-American aristocracy clinking cups in gardens and drawing rooms, Ivory, the survivor, is ready to spill the tea.

Merchant and Ivory, normally working with the writer Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, were one of the most dominant cinematic forces of the late 20th century, rolling out luxuriously appointed adaptations of E.M. Forster and Henry James novels, with the occasional more contemporary anomaly like Tama Janowitz’s “Slaves of New York.” Merchant died in 2005; Jhabvala in 2013. After decades conjuring the Anglo-American aristocracy clinking cups in gardens and drawing rooms, Ivory, the survivor, is ready to spill the tea.