Category: Recommended Reading

Berlin Views

Marek Zagańczyk at New England Review:

But Berlin is also a city receptive to wanderers conversing with death, loners who find themselves at the end of the road. For the Polish reader, there is no more important description of Berlin, of its mood, people, and places—all of them passed by with equal haste—than the fragments, from 1963, of Witold Gombrowicz’s diary. These pages offer a valuable introduction to the city; reading them carefully sends shivers down the spine. It is necessary to treat them as a standard of free writing and of a literature always on the side of life, though also one that is drawn towards life’s final moments.

But Berlin is also a city receptive to wanderers conversing with death, loners who find themselves at the end of the road. For the Polish reader, there is no more important description of Berlin, of its mood, people, and places—all of them passed by with equal haste—than the fragments, from 1963, of Witold Gombrowicz’s diary. These pages offer a valuable introduction to the city; reading them carefully sends shivers down the spine. It is necessary to treat them as a standard of free writing and of a literature always on the side of life, though also one that is drawn towards life’s final moments.

It is impossible to forget his metaphor for death, which, lurking, “perches on the arm like a bird.” In these fragments, hands are presented as protagonists of the first order, as if their pantomimes embodied the spirit of the city. The hands of Berliners are always moving: they manufacture, produce, spin—avoiding inaction at all costs.

more here.

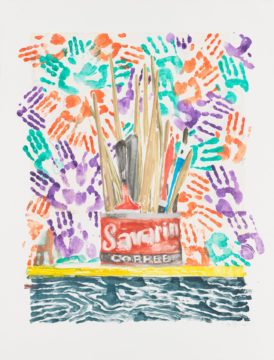

Jasper Johns Remains Contemporary Art’s Philosopher King

Peter Schjeldahl at The New Yorker:

His styles are legion—well organized in this show by the curators Scott Rothkopf, in New York, and Carlos Basualdo, in Philadelphia, with contrasts and echoes that forestall a possibility of feeling overwhelmed. Each place tells a complete story. Regarding early work, New York gets most of the Flags and Philadelphia most of the Numbers. Again, looking rules, as in the case of my favorite paintings of Johns’s mid-career phase, spectacular variations on color-field abstraction that present allover clusters of diagonal marks—that is, hatchings. These are often misleadingly termed “crosshatch,” even by Johns himself, but the marks never cross. Each bundle has a zone of the picture plane to itself, to keep his designs stretched flat, while they are supercharged by plays of touch and color and sometimes poeticized with piquant titles: “Corpse and Mirror,” for example, or “Scent.”

His styles are legion—well organized in this show by the curators Scott Rothkopf, in New York, and Carlos Basualdo, in Philadelphia, with contrasts and echoes that forestall a possibility of feeling overwhelmed. Each place tells a complete story. Regarding early work, New York gets most of the Flags and Philadelphia most of the Numbers. Again, looking rules, as in the case of my favorite paintings of Johns’s mid-career phase, spectacular variations on color-field abstraction that present allover clusters of diagonal marks—that is, hatchings. These are often misleadingly termed “crosshatch,” even by Johns himself, but the marks never cross. Each bundle has a zone of the picture plane to itself, to keep his designs stretched flat, while they are supercharged by plays of touch and color and sometimes poeticized with piquant titles: “Corpse and Mirror,” for example, or “Scent.”

more here.

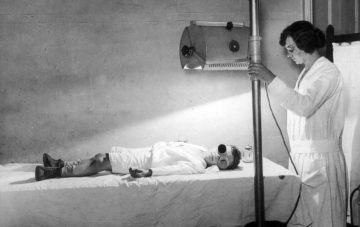

Energy, and How to Get It

Nick Paumgarten in The New Yorker:

For months, during the main pandemic stretch, I’d get inexplicably tired in the afternoon, as though vital organs and muscles had turned to Styrofoam. Just sitting in front of a computer screen, in sweatpants and socks, left me drained. It seemed ridiculous to be grumbling about fatigue when so many people were suffering through so much more. But we feel how we feel. Nuke a cup of cold coffee, take a walk around the block: the standard tactics usually did the trick. But one advantage, or disadvantage, of working from home is the proximity of a bed. Now and then, you surrender. These midafternoon doldrums weren’t entirely unfamiliar. Even back in the office years, with editors on the prowl, I learned to sneak the occasional catnap under my desk, alert as a zebra to the telltale footfall of a consequential approach. At home, though, you could power all the way down.

For months, during the main pandemic stretch, I’d get inexplicably tired in the afternoon, as though vital organs and muscles had turned to Styrofoam. Just sitting in front of a computer screen, in sweatpants and socks, left me drained. It seemed ridiculous to be grumbling about fatigue when so many people were suffering through so much more. But we feel how we feel. Nuke a cup of cold coffee, take a walk around the block: the standard tactics usually did the trick. But one advantage, or disadvantage, of working from home is the proximity of a bed. Now and then, you surrender. These midafternoon doldrums weren’t entirely unfamiliar. Even back in the office years, with editors on the prowl, I learned to sneak the occasional catnap under my desk, alert as a zebra to the telltale footfall of a consequential approach. At home, though, you could power all the way down.

Still, the ebb, lately, had become acute, and hard to account for. By the standards of my younger years, I was burning the candle at neither end. Could one attribute it to the wine the night before, the cookies, the fitful and abbreviated sleep, the boomerang effect of the morning’s caffeine and carbs, a sedentary profession, middle age? That will be a yes. And yet the mind roamed: covid? Lyme? Diabetes? Cancer? It’s no hipaa violation to reveal that, as various checkups determined, none of those pertained. So, embrace it. A recent headline in the Guardian: “Extravagant eye bags: How extreme exhaustion became this year’s hottest look.”

It was just a question of energy. The endurance athlete, running perilously low on fuel, is said to hit the wall, or bonk. Cyclists call this feeling “the man with the hammer.” Applying the parlance to the Sitzfleisch life, I told myself that I was bonking. At hour five in the desk chair, the document onscreen looked like a winding road toward a mountain pass. The man in the sweatpants had met the man with the mattress.

More here.

Paul McCartney knew he’d never top The Beatles — and that’s just fine with him

Terry Gross as heard on NPR:

It’s been more than 50 years since The Beatles disbanded, and Paul McCartney wants to set the record straight: “It’s always looked like I broke up The Beatles, and that wasn’t the case,” he says. McCartney traces the rumor to the 1970 documentary Let It Be, which followed the bandmates as they wrote, rehearsed and recorded the songs for their final album. The film and the subsequent press coverage created a narrative that pointed to Paul as the instigator of the breakup, and the story was so pervasive that McCartney even began to doubt himself. “I kind of bought into that a little bit,” he says. “And although I knew it wasn’t true, it affected me enough for me to just be unsure of myself.”

It’s been more than 50 years since The Beatles disbanded, and Paul McCartney wants to set the record straight: “It’s always looked like I broke up The Beatles, and that wasn’t the case,” he says. McCartney traces the rumor to the 1970 documentary Let It Be, which followed the bandmates as they wrote, rehearsed and recorded the songs for their final album. The film and the subsequent press coverage created a narrative that pointed to Paul as the instigator of the breakup, and the story was so pervasive that McCartney even began to doubt himself. “I kind of bought into that a little bit,” he says. “And although I knew it wasn’t true, it affected me enough for me to just be unsure of myself.”

…”We were just like most young guys. We just wanted to have a girlfriend and basically do as much as we could, was the idea. So as we got fans, that became our motivation, which was, we were trying to be attractive in any way you like — visually, physically, sexually. We didn’t mind, as long as we were attractive, because as kids, we were apparently not very attractive and we certainly weren’t the big kind of quarterback who attracted all the girls in town. It was kind of the opposite for us, so I suppose, as we got more and more popular and the girls started screaming, to tell you the truth, we just enjoyed it. It was the fulfillment of all our dreams. … It really was just we young guys trying to get laid, as Americans would say.”

On how the screaming of Beatlemania got old

“Later then, it got a bit worrying because now the first sort of flush of the excitement had been going for quite a few years and we were maturing and we were sort of out of that phase. It was like, OK, it would be quite nice to be able to hear the song we’re playing. And we couldn’t because it was just a million seagulls screaming.”

More here.

Wednesday, November 3, 2021

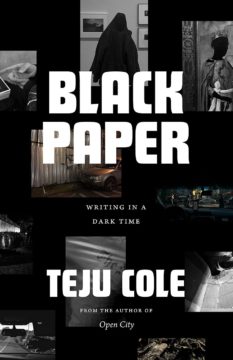

Teju Cole on the Wonder of Epiphanic Writing

Teju Cole in Literary Hub:

The idea of epiphany summons two thoughts, generally. One is religious: the sudden and overwhelming appearance of the Divine into everyday life, as experienced, for instance, by Julian of Norwich, Teresa of Avila, and many holy figures through the ages. The other is literary. Epiphany is now perhaps as strongly, or even more strongly, connected to a certain idea expressed in European modernism, and emphasized in its aftermath. The idea is especially prominent in Joyce’s two early prose works, Dubliners—which includes “The Dead”—and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Epiphany, as understood by Joyce, and practiced thereafter, has to do with heightened sensation and flashes of insight, often of the kind that helps a character solve a problem. This is the definition he gave the term, in an early version of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: “a sudden spiritual manifestation.”

The idea of epiphany summons two thoughts, generally. One is religious: the sudden and overwhelming appearance of the Divine into everyday life, as experienced, for instance, by Julian of Norwich, Teresa of Avila, and many holy figures through the ages. The other is literary. Epiphany is now perhaps as strongly, or even more strongly, connected to a certain idea expressed in European modernism, and emphasized in its aftermath. The idea is especially prominent in Joyce’s two early prose works, Dubliners—which includes “The Dead”—and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Epiphany, as understood by Joyce, and practiced thereafter, has to do with heightened sensation and flashes of insight, often of the kind that helps a character solve a problem. This is the definition he gave the term, in an early version of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: “a sudden spiritual manifestation.”

“The Dead” begins at an annual Christmas gathering for friends and family in Dublin early in the 20th century. After the party, we are with a couple, the Conroys, heading to their hotel. And then we are with just the troubled thoughts of Gabriel Conroy, who is ruminating on what his wife Gretta has just told him about something in her deep past: when she was a girl, she loved a boy and the boy loved her.

More here.

Justin E. H. Smith asks Sean Carroll “What is Matter?”

Andrew Sullivan speaks with Steven Pinker on rationality in our tribal times

Yanis Varoufakis: A Progressive Monetary Policy Is the Only Alternative

Yanis Varoufakis in Project Syndicate:

As the coronavirus pandemic recedes in the advanced economies, their central banks increasingly resemble the proverbial ass who, equally hungry and thirsty, succumbs to both hunger and thirst because it could not choose between hay and water. Torn between inflationary jitters and fear of deflation, policymakers are taking a potentially costly wait-and-see approach. Only a progressive rethink of their tools and aims can help them play a socially useful post-pandemic role.

As the coronavirus pandemic recedes in the advanced economies, their central banks increasingly resemble the proverbial ass who, equally hungry and thirsty, succumbs to both hunger and thirst because it could not choose between hay and water. Torn between inflationary jitters and fear of deflation, policymakers are taking a potentially costly wait-and-see approach. Only a progressive rethink of their tools and aims can help them play a socially useful post-pandemic role.

Central bankers once had a single policy lever: interest rates. Push down to revitalize a flagging economy; push up to rein in inflation (often at the expense of triggering a recession). Timing these moves, and deciding by how much to move the lever, was never easy, but at least there was only one move to make: push the lever up or down. Today, central bankers’ work is twice as complicated, because, since 2009, they have had two levers to manipulate.

Following the 2008 global financial crisis, a second lever became necessary, because the original one got jammed: Even though it had been pushed down as far as possible, driving interest rates to zero and often forcing them into negative territory, the economy continued to stagnate. Taking a page from the Bank of Japan, major central banks (led by the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England) created a second lever, known as quantitative easing (QE).

More here.

Teju Cole Interview: My Looking Became Sacred

On Edward Said’s Love Of Music And Late Beethoven

Teju Cole at Bookforum:

Edward Said loved music, and I loved his love of music as well as the musicality that characterized everything he did. Because of his writings on late style, I think of him in connection with Beethoven’s String Quartet no. 15, op. 132. This was Beethoven’s thirteenth quartet, but the fifteenth in order of publication. It’s the kind of work that tempts one to agree with the strange notion that there is such a thing as pure music, music better than any possible performance. This is a romantic idea, and it’s probably not true, since music exists in the hearing, not on the page. But listening to Beethoven’s Op. 132, you can see why people think so. Within the written tradition of Western classical music, as in all genres of music, there is music that exhausts superlatives. Late Beethoven emerges coherently out of mature Beethoven, and mature Beethoven is an extension and fulfillment of early Beethoven. These are major shifts and distinct modes of evolution, but they are not radical breaks.

Edward Said loved music, and I loved his love of music as well as the musicality that characterized everything he did. Because of his writings on late style, I think of him in connection with Beethoven’s String Quartet no. 15, op. 132. This was Beethoven’s thirteenth quartet, but the fifteenth in order of publication. It’s the kind of work that tempts one to agree with the strange notion that there is such a thing as pure music, music better than any possible performance. This is a romantic idea, and it’s probably not true, since music exists in the hearing, not on the page. But listening to Beethoven’s Op. 132, you can see why people think so. Within the written tradition of Western classical music, as in all genres of music, there is music that exhausts superlatives. Late Beethoven emerges coherently out of mature Beethoven, and mature Beethoven is an extension and fulfillment of early Beethoven. These are major shifts and distinct modes of evolution, but they are not radical breaks.

more here.

Can The Memoir Capture The Mysteries Of Childhood?

John Banville at The Nation:

Any account of childhood written by an adult might quickly become a work of adult art, presenting the child’s world, its highlights and its shadows, with a sensibility foreign to the experiences of being young. With his intensely concentrated gaze and voluptuous yet exact prose style, however, Wollheim offers us a work of vivid immediacy. Reading it, one experiences the kind of embarrassment that the critic Christopher Ricks identified in Keats’s poetry: Brought this close up to what it feels like to be a child, or for that matter an adult, Wollheim helps us see with awful clarity what an emotional and moral predicament it is to be alive.

Any account of childhood written by an adult might quickly become a work of adult art, presenting the child’s world, its highlights and its shadows, with a sensibility foreign to the experiences of being young. With his intensely concentrated gaze and voluptuous yet exact prose style, however, Wollheim offers us a work of vivid immediacy. Reading it, one experiences the kind of embarrassment that the critic Christopher Ricks identified in Keats’s poetry: Brought this close up to what it feels like to be a child, or for that matter an adult, Wollheim helps us see with awful clarity what an emotional and moral predicament it is to be alive.

Afitting epigraph to Germs could be Philip Larkin’s stark yet somehow comic line “Life is first boredom, then fear.”

more here.

AI Generates Hypotheses Human Scientists Have Not Thought Of

Robin Blades in Scientific American:

Electric vehicles have the potential to substantially reduce carbon emissions, but car companies are running out of materials to make batteries. One crucial component, nickel, is projected to cause supply shortages as early as the end of this year. Scientists recently discovered four new materials that could potentially help—and what may be even more intriguing is how they found these materials: the researchers relied on artificial intelligence to pick out useful chemicals from a list of more than 300 options. And they are not the only humans turning to A.I. for scientific inspiration.

Electric vehicles have the potential to substantially reduce carbon emissions, but car companies are running out of materials to make batteries. One crucial component, nickel, is projected to cause supply shortages as early as the end of this year. Scientists recently discovered four new materials that could potentially help—and what may be even more intriguing is how they found these materials: the researchers relied on artificial intelligence to pick out useful chemicals from a list of more than 300 options. And they are not the only humans turning to A.I. for scientific inspiration.

Creating hypotheses has long been a purely human domain. Now, though, scientists are beginning to ask machine learning to produce original insights. They are designing neural networks (a type of machine-learning setup with a structure inspired by the human brain) that suggest new hypotheses based on patterns the networks find in data instead of relying on human assumptions. Many fields may soon turn to the muse of machine learning in an attempt to speed up the scientific process and reduce human biases.

In the case of new battery materials, scientists pursuing such tasks have typically relied on database search tools, modeling and their own intuition about chemicals to pick out useful compounds. Instead a team at the University of Liverpool in England used machine learning to streamline the creative process. The researchers developed a neural network that ranked chemical combinations by how likely they were to result in a useful new material. Then the scientists used these rankings to guide their experiments in the laboratory. They identified four promising candidates for battery materials without having to test everything on their list, saving them months of trial and error.

More here.

The developing world has much bigger problems than climate change

From Spiked:

Heralding the start of the COP26 climate talks yesterday, UK prime minister Boris Johnson warned that the world is ‘one minute to midnight’ in its fight against climate change. The world leaders gathered in Glasgow say they are saving the planet from an existential threat. But does the fate of humanity really hang in the balance? And could climate alarmism do more harm than good?

Bjorn Lomborg is a climate economist and a self-described sceptical environmentalist. His latest book is False Alarm: How Climate Change Panic Costs Us Trillions, Hurts the Poor, and Fails to Fix the Planet. He joined Brendan O’Neill for the latest episode of his podcast, The Brendan O’Neill Show, to talk about where the world is going wrong on climate change. What follows is an edited extract from their conversation. Listen to the full episode here.

Brendan O’Neill: At COP26, there will be lots of discussion, lots of statements and lots of dashed hopes and ambitions. What do you make of global gatherings of this kind? Do they do any good in terms of tackling climate change or making the world a better place?

Bjorn Lomborg: They probably make the world a slightly better place. But the giveaway is in the number 26 – this is the 26th time that we have tried this. We have been trying since 1992, when we signed the Rio Convention. The entire rich world failed to follow through on it. Then we had the Kyoto Protocol and again most parties failed to live up to their promises. Then we had the Paris Agreement and now we have Glasgow. The Glasgow conference is supposed to go even further than Paris did.

More here.

Wednesday Poem

A Dispatch From Seattle or, Nervous in the Hot Zone

Yes, we’re scared but we also make

zombie apocalypse jokes

By texts. I don’t know when I’ll see

my friends in person again.

We don’t want to panic and overreact

but we don’t want

To underreact. Some of my friends

are still hosting parties.

Some of them are still planning

to take their previously

Scheduled trips overseas. Some are

the polite looters

Who are buying all the toilet paper

in Seattle.

“Good for you,” I text to one of them.

“You’ll be

The most hygienic and well-stocked

shitter in the city.”

Some of my fellow Native Americans

are performing

The highly sacred Indigenous shrug,

as in, “Dude,

They’re not giving us smallpox

blankets.”

But, hey, it’s the Trumps. Their

wicked incompetence

Tuesday, November 2, 2021

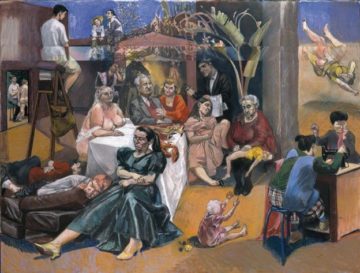

Paula Rego: Yes, With A Growl

Morgan Meis in The Easel:

There’s a painting entitled Celestina’s House (2000-1). I count at least twenty-two figures in the painting. That’s a rough count. A few of these figures are sitting around a table, presumably eating a meal, though the only food on the table is a lobster and crab, maybe still alive. In front of the table, several figures nap awkwardly on pillows while, nearby, a tiny old woman sits on the floor, reaching up like a baby. Elsewhere, two women work, disconsolate, at a sewing machine, another woman falls down backward through the air, and a young fellow sits on a ladder with his back to us, as if he’s being punished. There is so much going on it is impossible to understand exactly what is going on. It is a scene, perhaps, showing us what would happen if the entire contents of many nights’ dreaming were smashed onto one canvas. The style is more or less realist, but not fastidiously so. We seem to be firmly in the realm of fantasy, memory, fable, and dream.

There’s a painting entitled Celestina’s House (2000-1). I count at least twenty-two figures in the painting. That’s a rough count. A few of these figures are sitting around a table, presumably eating a meal, though the only food on the table is a lobster and crab, maybe still alive. In front of the table, several figures nap awkwardly on pillows while, nearby, a tiny old woman sits on the floor, reaching up like a baby. Elsewhere, two women work, disconsolate, at a sewing machine, another woman falls down backward through the air, and a young fellow sits on a ladder with his back to us, as if he’s being punished. There is so much going on it is impossible to understand exactly what is going on. It is a scene, perhaps, showing us what would happen if the entire contents of many nights’ dreaming were smashed onto one canvas. The style is more or less realist, but not fastidiously so. We seem to be firmly in the realm of fantasy, memory, fable, and dream.

The artist is Paula Rego. Rego is originally from Portugal (b. 1935) but has lived much of her life in England. Her work has been celebrated in England and to some degree in her native Portugal, but is not as well known elsewhere. She exhibited with the so-called London Group in the 1960s, a group that included David Hockney, Barbara Hepworth, and Frank Auerbach. Recently, The Tate has mounted an exhibit billed as “the UK’s largest and most comprehensive retrospective of Paula Rego’s work to date.” Critical response to the show has been rapturous and widespread. At eighty-six years of age, Rego seems finally to be getting the recognition she deserves.

More here.

UN Secretary-General: COP26 Must Keep 1.5 Degrees Celsius Goal Alive

António Guterres at COP26 World Leaders Summit:

Dear Prime Minister Boris Johnson, I want to thank you and COP President Alok Sharma for your hospitality, leadership, and tireless efforts in the preparation of this COP.

Dear Prime Minister Boris Johnson, I want to thank you and COP President Alok Sharma for your hospitality, leadership, and tireless efforts in the preparation of this COP.

Your Royal Highnesses, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen,

The six years since the Paris Climate Agreement have been the six hottest years on record.

Our addiction to fossil fuels is pushing humanity to the brink.

We face a stark choice: Either we stop it — or it stops us.

It’s time to say: enough.

Enough of brutalizing biodiversity.

Enough of killing ourselves with carbon.

Enough of treating nature like a toilet.

Enough of burning and drilling and mining our way deeper.

We are digging our own graves.

More here.

How Hidden Technology Transformed Bowling

The JFK Cover-Up Strikes Again

James K. Galbraith in Project Syndicate:

Brood with me on the latest delay of the full release of the records pertaining to the murder of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas on November 22, 1963. That was 58 years ago. More time has passed since October 26, 1992, when Congress mandated the full and immediate release of almost all the JFK assassination records, than had elapsed between the killing and the passage of that law.

Brood with me on the latest delay of the full release of the records pertaining to the murder of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas on November 22, 1963. That was 58 years ago. More time has passed since October 26, 1992, when Congress mandated the full and immediate release of almost all the JFK assassination records, than had elapsed between the killing and the passage of that law.

The late Senator John Glenn of Ohio – an astronaut-hero of the Kennedy era – wrote the 1992 law. It stipulates that “all Government records concerning the assassination … should carry a presumption of immediate disclosure, and all records should be eventually disclosed.” The law states that “only in the rarest cases is there any legitimate need for continued protection of such records.”

Congress was precise in specifying where such a need might exist. Protecting the identity of an intelligence agent who “currently requires protection” was one case. Likewise, any intelligence source or method “currently utilized” deserved protection. In some cases, privacy concerns might be paramount. Finally, there was language exempting any other matter relating to “defense, intelligence operations, or the conduct of foreign relations, the disclosure of which would demonstrably impair the national security of the United States.”

More here.

Technofeudalism: Varoufakis and Zizek