Benjamin Braun and Adrienne Buller also in Phenomenal World (image: Joëlle Tuerlinckx, ‘the biggest-surface-on-earth scale 1:1’ (‘la-plus-grande-surface-au-monde scale 1:1’), 2006)

Benjamin Braun and Adrienne Buller also in Phenomenal World (image: Joëlle Tuerlinckx, ‘the biggest-surface-on-earth scale 1:1’ (‘la-plus-grande-surface-au-monde scale 1:1’), 2006)

In mid October 2021, when BlackRock revealed its third quarter results, the asset management behemoth announced it was just shy of $10 trillion in assets under management. It’s a vast sum, “roughly equivalent to the entire global hedge fund, private equity and venture capital industries combined,” and a nearly ten-fold increase in only a handful of years for a firm that first broke the $1 trillion mark as recently as 2009. Since the 2008 Financial Crisis, we’ve witnessed in BlackRock the rise of an undisputed shareholder superpower, but the firm, while exceptional, is not alone. Alongside its closest rival Vanguard, these two firms control nearly $20 trillion in assets and a combined market share of more than 50 percent in the booming market for exchange-traded funds (ETFs). And they’re not just big—they’re “universal,” controlling major stakes in every firm, asset class, industry, and geography of the global economy. It’s an unprecedented conjuncture of concentration and distribution, one which has prompted fierce debate over what this new era of common, universal, and increasingly passively allocated ownership means. For some, the new regime contains the seeds of a socialist-utopian economic vision; for others, it’s an anticompetitive, “worse than Marxism” nightmare.

At the heart of the debate is the theory of universal ownership, which contends that because today’s asset management giants are universal owners with fully diversified portfolios, they should be structurally motivated to internalize the negative externalities that arise from the conduct of individual corporations or sectors. Whether social inequality or the climate crisis, proponents of universal ownership contend that the enormous externalities of corporate capitalism will, eventually, diminish shareholder returns, and therefore universal owners should and will act to minimize them. It’s an elegant theory, but is it true? Ultimately, the answer to this question hinges on how we understand ownership.

More here.

Ajay Singh Chaudhary in The Baffler (image

Ajay Singh Chaudhary in The Baffler (image  Herman Mark Schwartz in Phenomenal World:

Herman Mark Schwartz in Phenomenal World: Something unnatural

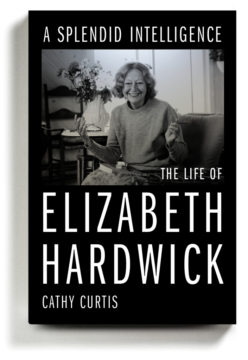

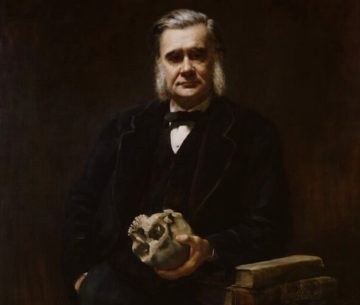

Something unnatural To be a literary biographer is to court the extravagant ridicule of the very people you write about. For all of the salutary services a writer’s biography can offer — the tracing of the life, the contextualizing of the work, the resuscitation of a reputation and the deliverance from neglect — the biographer has been derided as a “post-mortem exploiter” (Henry James) and a “professional burglar” (Janet Malcolm).

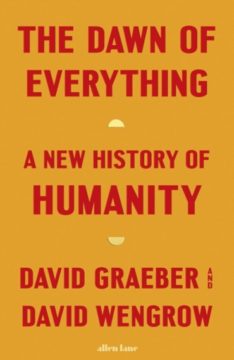

To be a literary biographer is to court the extravagant ridicule of the very people you write about. For all of the salutary services a writer’s biography can offer — the tracing of the life, the contextualizing of the work, the resuscitation of a reputation and the deliverance from neglect — the biographer has been derided as a “post-mortem exploiter” (Henry James) and a “professional burglar” (Janet Malcolm). The standard history of humanity goes something like this. Roughly 300,000 to 200,000 years ago, Homo sapiens first evolved somewhere on the African continent. Over the next 100,000 to 150,000 years, this sturdy, adaptable species moved into new regions, first on its home continent and then into other parts of the globe. These early humans shaped flint and other stones into cutting blades of increasing complexity and used their tools to hunt the mega-fauna of the Pleistocene era. Sometimes, they immortalized these hunts—carved on rock faces or painted in glorious murals across the walls and ceilings of caves in places like Sulawesi, Chauvet, and Lascaux.

The standard history of humanity goes something like this. Roughly 300,000 to 200,000 years ago, Homo sapiens first evolved somewhere on the African continent. Over the next 100,000 to 150,000 years, this sturdy, adaptable species moved into new regions, first on its home continent and then into other parts of the globe. These early humans shaped flint and other stones into cutting blades of increasing complexity and used their tools to hunt the mega-fauna of the Pleistocene era. Sometimes, they immortalized these hunts—carved on rock faces or painted in glorious murals across the walls and ceilings of caves in places like Sulawesi, Chauvet, and Lascaux. It’s easy to mock the Corporation Formerly Known As Facebook. Mark Zuckerberg’s announcement that Facebook would

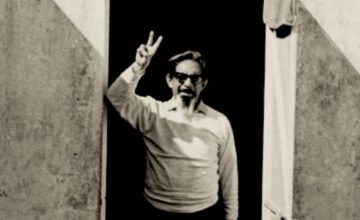

It’s easy to mock the Corporation Formerly Known As Facebook. Mark Zuckerberg’s announcement that Facebook would  A LITTLE OVER halfway through his 1943 novel El luto humano (Human Mourning), the Mexican writer José Revueltas inserts himself as a character so unobtrusively that it’s easy to miss. A government go-between, when hiring an assassin to kill the leader of an agricultural strike, complains, “First there was the agitation sown by José de Arcos, Revueltas, Salazar, García, and the other Communists. […] And now all over again…” It’s a sly wink at the fact that the novel’s scenario overlaps with the author’s life; it also foreshadows the way that Revueltas’s place in Mexican letters today is inextricably entwined with his dramatic biography.

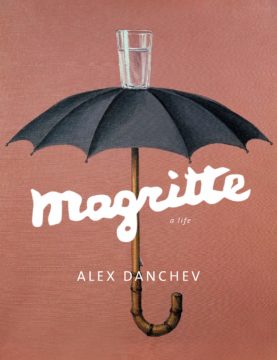

A LITTLE OVER halfway through his 1943 novel El luto humano (Human Mourning), the Mexican writer José Revueltas inserts himself as a character so unobtrusively that it’s easy to miss. A government go-between, when hiring an assassin to kill the leader of an agricultural strike, complains, “First there was the agitation sown by José de Arcos, Revueltas, Salazar, García, and the other Communists. […] And now all over again…” It’s a sly wink at the fact that the novel’s scenario overlaps with the author’s life; it also foreshadows the way that Revueltas’s place in Mexican letters today is inextricably entwined with his dramatic biography. The instant recognisability of Magritte’s work has its roots not in his training at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels from 1916 to 1918 but in his postwar work as a draughtsman in the city from 1922 to 1926. During this time he made artworks for advertising companies and designed wallpaper and posters. The skills garnered from the first two of these are immediately evident in Golconda, now in the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas. The bowler-hatted men, part Thomson and Thompson, part Gilbert and George, are as obviously Magritte’s logo as the part-eaten apple is that of a certain American computer giant. His eye for pattern was also acute. Golconda would make lovely wallpaper, and no doubt has.

The instant recognisability of Magritte’s work has its roots not in his training at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels from 1916 to 1918 but in his postwar work as a draughtsman in the city from 1922 to 1926. During this time he made artworks for advertising companies and designed wallpaper and posters. The skills garnered from the first two of these are immediately evident in Golconda, now in the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas. The bowler-hatted men, part Thomson and Thompson, part Gilbert and George, are as obviously Magritte’s logo as the part-eaten apple is that of a certain American computer giant. His eye for pattern was also acute. Golconda would make lovely wallpaper, and no doubt has. Depending on the outcome of social conflicts, ants of the species Harpegnathos saltator do something unusual: they can switch from a worker to a queen-like status known as gamergate. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Cell on November 4th have made the surprising discovery that a single protein, called Kr-h1 (Krüppel homolog 1), responds to socially regulated hormones to orchestrate this complex social transition.

Depending on the outcome of social conflicts, ants of the species Harpegnathos saltator do something unusual: they can switch from a worker to a queen-like status known as gamergate. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Cell on November 4th have made the surprising discovery that a single protein, called Kr-h1 (Krüppel homolog 1), responds to socially regulated hormones to orchestrate this complex social transition. “Ever since I have been at court,” exclaimed the vidame, “the queen has always treated me with much distinction and amiability, and I have reason to believe she has had a kindly feeling for me. Yet there was nothing marked about it, and I had never dreamed of other feelings toward me than those of respect. I was even much in love with Madame de Themines. The sight of her is enough to prove that a man can have a great deal of love for her when she loves him—and she loved me.

“Ever since I have been at court,” exclaimed the vidame, “the queen has always treated me with much distinction and amiability, and I have reason to believe she has had a kindly feeling for me. Yet there was nothing marked about it, and I had never dreamed of other feelings toward me than those of respect. I was even much in love with Madame de Themines. The sight of her is enough to prove that a man can have a great deal of love for her when she loves him—and she loved me. In 1966, I was a junior at St. Louis’s Kirkwood High. After the teachers let us monkeys out at 2:50, I lazed about, often trekking to a friend’s home to talk antiwar politics or Salinger stories. I was a serious kid, some days lying on one of the twin beds in Ken Klotz’s room (his unlucky brother off in Vietnam) where we were hypnotized by Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde and the literary dazzle of “Visions of Johanna”: “The ghost of electricity howls from the bones of her face.” But then some days I needed a break.

In 1966, I was a junior at St. Louis’s Kirkwood High. After the teachers let us monkeys out at 2:50, I lazed about, often trekking to a friend’s home to talk antiwar politics or Salinger stories. I was a serious kid, some days lying on one of the twin beds in Ken Klotz’s room (his unlucky brother off in Vietnam) where we were hypnotized by Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde and the literary dazzle of “Visions of Johanna”: “The ghost of electricity howls from the bones of her face.” But then some days I needed a break.