Philip Ball at Marginalia Review:

Just how experimentally constrained scientific theories are is a matter that has long been debated (and still is) by philosophers of science. And it’s surely no coincidence that they, like historians, are another scholarly group regularly dismissed and belittled by some practicing scientists as being irrelevant to the daily business of science. But in any event, many scientists seem determined to regard science and the knowledge it produces in Platonic terms: as rising rapidly above the histories, personalities, and social milieu that generate it.

Just how experimentally constrained scientific theories are is a matter that has long been debated (and still is) by philosophers of science. And it’s surely no coincidence that they, like historians, are another scholarly group regularly dismissed and belittled by some practicing scientists as being irrelevant to the daily business of science. But in any event, many scientists seem determined to regard science and the knowledge it produces in Platonic terms: as rising rapidly above the histories, personalities, and social milieu that generate it.

Sure, they might say, Darwinism was misused in its early days, when it was still poorly understood, to support racism, eugenics and a host of other prejudices of the times. But now we really know what it means! And this notwithstanding the fact that still today leading scientists will argue about whether natural selection makes eugenics meaningfully possible in principle (while new biomedical technologies resurrect its spectre), or whether there are genetic distinctions that give rise to different characteristics between racial groups. The idea that all dubious sociopolitical considerations have long since been sifted out of such scientific theories is ludicrous and ahistorical special pleading.

more here.

GIDDY FROM SIPPING FLUTES of the de Young Museum’s prosecco, my friend Karen and I quickly realized that from the VIP section, the view of Judy Chicago’s smoke sculpture,

GIDDY FROM SIPPING FLUTES of the de Young Museum’s prosecco, my friend Karen and I quickly realized that from the VIP section, the view of Judy Chicago’s smoke sculpture,  Fifty years ago, at a harp recital in Gloucestershire, a retired British military officer with a clipped aristo accent came across a brown-skinned teenager. “I say, old chap, do you speak English?” the officer said. As a story in Yale’s New Journal recounted, the young man—Kwame Anthony Akroma-Ampim Kusi Appiah—replied, “Why don’t you ask my grandmother?”

Fifty years ago, at a harp recital in Gloucestershire, a retired British military officer with a clipped aristo accent came across a brown-skinned teenager. “I say, old chap, do you speak English?” the officer said. As a story in Yale’s New Journal recounted, the young man—Kwame Anthony Akroma-Ampim Kusi Appiah—replied, “Why don’t you ask my grandmother?” Vaccine

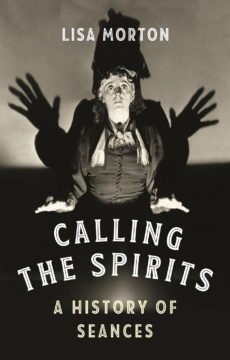

Vaccine  As Lisa Morton notes in Calling the Spirits: A History of Seances, there is not a shred of scientific evidence that proves the existence of spirits or any ability on our part or theirs, if they did exist, that we can communicate with them. (298) Despite this, there is hardly a culture or people on earth that has not or does not believe in a spiritual life of some sort after death and that does not have some sort of ritual conducted by a “specialist” to communicate with the dead. Human beings are convinced, and have been throughout history, that there is an afterlife, that death is not the end but simply a gateway to more life, and that this afterlife has some profound effect upon those still living this life. What this pervasive belief shows is:

As Lisa Morton notes in Calling the Spirits: A History of Seances, there is not a shred of scientific evidence that proves the existence of spirits or any ability on our part or theirs, if they did exist, that we can communicate with them. (298) Despite this, there is hardly a culture or people on earth that has not or does not believe in a spiritual life of some sort after death and that does not have some sort of ritual conducted by a “specialist” to communicate with the dead. Human beings are convinced, and have been throughout history, that there is an afterlife, that death is not the end but simply a gateway to more life, and that this afterlife has some profound effect upon those still living this life. What this pervasive belief shows is: If my father occasionally enjoyed falsifying his ancestry for a bit of role-playing fun on the French Riviera (I don’t believe it ever went very far, though he may once have gained admission with this ruse to a party at the vacation home of Sally Jessy Raphael), I have tended to adopt the opposite evolutionary strategy as I move through rather different social circles than those I may once have been expected to end up in. When an animal is threatened, it can puff itself up to appear even more threatening than its adversary, as a cat does; or it can lie prostrate like an opossum, even generating from within its living body the stench of death itself. While I have never been so desperate as to slip into thanatosis, I have often gone out of my way to imply, in rarefied social settings, that my own origins “stink”, that I come from the pure stock of Dustbowl migrants, from a sort of topsy-turvy farce of aristocracy in which you convince others that you are somebody precisely by establishing that you are descended from absolutely nobody.

If my father occasionally enjoyed falsifying his ancestry for a bit of role-playing fun on the French Riviera (I don’t believe it ever went very far, though he may once have gained admission with this ruse to a party at the vacation home of Sally Jessy Raphael), I have tended to adopt the opposite evolutionary strategy as I move through rather different social circles than those I may once have been expected to end up in. When an animal is threatened, it can puff itself up to appear even more threatening than its adversary, as a cat does; or it can lie prostrate like an opossum, even generating from within its living body the stench of death itself. While I have never been so desperate as to slip into thanatosis, I have often gone out of my way to imply, in rarefied social settings, that my own origins “stink”, that I come from the pure stock of Dustbowl migrants, from a sort of topsy-turvy farce of aristocracy in which you convince others that you are somebody precisely by establishing that you are descended from absolutely nobody. Many writers and researchers suggested that the presence of a high-containment laboratory in Wuhan, the Wuhan Institute of Virology, could point to a laboratory origin for the pandemic: a bioweapons experiment; or

Many writers and researchers suggested that the presence of a high-containment laboratory in Wuhan, the Wuhan Institute of Virology, could point to a laboratory origin for the pandemic: a bioweapons experiment; or  When journalist

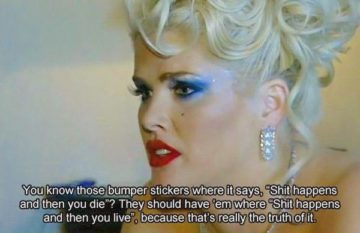

When journalist  Here was a woman who had modelled her life so closely on Marilyn Monroe’s that doing so eventually helped drive her to her death – the blonde waves and the fake breasts; the pill addictions and the airheaded pronouncements about men and sex and diamonds; the years spent tumbling down the rabbit-hole in search of somebody with cash willing to play at being Daddy; the PLAYBOY cover and centrefold, and the unwise sexual exhibitionism, and the occasional moments of bleak honesty that nodded at some formative abuse – and yet still she achieved twice the thing that Monroe never did: for four days, from 7 September 2006 to 10 September 2006, Anna Nicole Smith was a mother to two children. As it had for Monroe, who confessed in her last year that she had wanted children ‘more than anything’, motherhood held as much significance for Smith as big-time fame did, her desire to be the world’s hottest chick only commensurate with her certainty that she should procreate. ‘I’m either going to be a very good, very famous movie star and model,’ Smith told ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY at the height of her success, in 1994, ‘or I’m going to have a bunch of kids. I would miss having a career, but I’ve done my acting, and I’ve done my modelling. I’ve done everything I wanted to do.’ She did not become a great actor, even if for a short time she was one of the biggest models on earth. She did not make it to 40, even though she outlived Monroe by 3 sad, medicated years, dying at the Hard Rock Hotel in Florida at just 39 years old, in 2007.

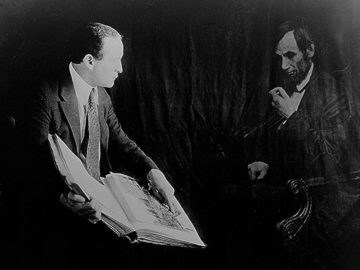

Here was a woman who had modelled her life so closely on Marilyn Monroe’s that doing so eventually helped drive her to her death – the blonde waves and the fake breasts; the pill addictions and the airheaded pronouncements about men and sex and diamonds; the years spent tumbling down the rabbit-hole in search of somebody with cash willing to play at being Daddy; the PLAYBOY cover and centrefold, and the unwise sexual exhibitionism, and the occasional moments of bleak honesty that nodded at some formative abuse – and yet still she achieved twice the thing that Monroe never did: for four days, from 7 September 2006 to 10 September 2006, Anna Nicole Smith was a mother to two children. As it had for Monroe, who confessed in her last year that she had wanted children ‘more than anything’, motherhood held as much significance for Smith as big-time fame did, her desire to be the world’s hottest chick only commensurate with her certainty that she should procreate. ‘I’m either going to be a very good, very famous movie star and model,’ Smith told ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY at the height of her success, in 1994, ‘or I’m going to have a bunch of kids. I would miss having a career, but I’ve done my acting, and I’ve done my modelling. I’ve done everything I wanted to do.’ She did not become a great actor, even if for a short time she was one of the biggest models on earth. She did not make it to 40, even though she outlived Monroe by 3 sad, medicated years, dying at the Hard Rock Hotel in Florida at just 39 years old, in 2007. Harry Houdini was just 52 when he

Harry Houdini was just 52 when he  Cora Currier in The New Republic:

Cora Currier in The New Republic: Aziz Z. Huq in Boston Review:

Aziz Z. Huq in Boston Review:

A

A  “You’re just a pawn in the game, you know,” a public security officer summarily informs Ai Weiwei, China’s most controversial — and to the Chinese Communist Party, its most dangerous — artist. It is 2011 and Ai, suspected of “inciting the subversion of state power,” has recently been held captive for 81 days; soon after his release, he is slapped with a tax bill equivalent to $2.4 million. According to the officer, Ai’s high profile has made him an expedient tool for Westerners to attack China, but “pawns sooner or later all get sacrificed.” Of course, it’s obvious that Ai also regards the officer as a pawn, one who, in serving an oppressive regime, has sacrificed his freedom to speak for himself.

“You’re just a pawn in the game, you know,” a public security officer summarily informs Ai Weiwei, China’s most controversial — and to the Chinese Communist Party, its most dangerous — artist. It is 2011 and Ai, suspected of “inciting the subversion of state power,” has recently been held captive for 81 days; soon after his release, he is slapped with a tax bill equivalent to $2.4 million. According to the officer, Ai’s high profile has made him an expedient tool for Westerners to attack China, but “pawns sooner or later all get sacrificed.” Of course, it’s obvious that Ai also regards the officer as a pawn, one who, in serving an oppressive regime, has sacrificed his freedom to speak for himself.