Dan Williams at Asterisk:

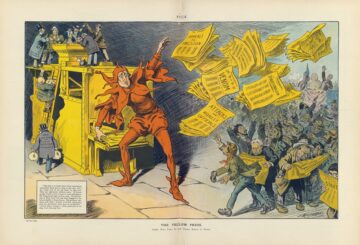

Many people sense that the United States is undergoing an epistemic crisis, a breakdown in the country’s collective capacity to agree on basic facts, distinguish truth from falsehood, and adhere to norms of rational debate.

Many people sense that the United States is undergoing an epistemic crisis, a breakdown in the country’s collective capacity to agree on basic facts, distinguish truth from falsehood, and adhere to norms of rational debate.

This crisis encompasses many things: rampant political lies; misinformation; and conspiracy theories; widespread beliefs in demonstrable falsehoods (“misperceptions”); intense polarization in preferred information sources; and collapsing trust in institutions meant to uphold basic standards of truth and evidence (such as science, universities, professional journalism, and public health agencies).

According to survey data, over 60% of Republicans believe Joe Biden’s presidency was illegitimate. 20% of Americans think vaccines are more dangerous than the diseases they prevent, and 36% think the specific risks of COVID-19 vaccines outweigh their benefits. Only 31% of Americans have at least a “fair amount” of confidence in mainstream media, while a record-high 36% have no trust at all.

What is driving these problems?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Where did Europe’s distinct Uralic family of languages — which includes Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian — come from? New research puts their origins a lot farther east than many thought.

Where did Europe’s distinct Uralic family of languages — which includes Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian — come from? New research puts their origins a lot farther east than many thought. My colleague Joseph Lowndes and I have been

My colleague Joseph Lowndes and I have been  Put a bagel in a toaster oven and push a button. In a few seconds, heating elements inside the oven glow red and heat the bagel. The action seems simple — after all, ten-year-olds routinely toast bagels without adult supervision. Matters look different if you inquire into what must happen to make the oven work. Pushing the button engages the mechanism of an incomprehensibly vast multinational network: the North American electrical grid.

Put a bagel in a toaster oven and push a button. In a few seconds, heating elements inside the oven glow red and heat the bagel. The action seems simple — after all, ten-year-olds routinely toast bagels without adult supervision. Matters look different if you inquire into what must happen to make the oven work. Pushing the button engages the mechanism of an incomprehensibly vast multinational network: the North American electrical grid. Less than two hours after sunrise, with the shadows still blue and slanting hard in a dense growth of balsam firs and spruces, the baby bird blundered into a fine black net strung along the ridgeline of Mount Mansfield, at 4,393 feet Vermont’s tallest mountain.

Less than two hours after sunrise, with the shadows still blue and slanting hard in a dense growth of balsam firs and spruces, the baby bird blundered into a fine black net strung along the ridgeline of Mount Mansfield, at 4,393 feet Vermont’s tallest mountain.  A human female is born with all the egg cells she will ever have. The possibility for the development of new oocytes is zero. Given this constraint, it is crucial that these gametes remain healthy and viable for decades until they are needed to form an embryo. Irrespective of the ‘age’ of the fertilized oocyte, the resulting embryo has the characteristics of a freshly born cell, indicating the existence of mechanisms that counteract accrued cellular damage and keep the egg fresh. What are these processes that drive the prolonged life of human egg cells?

A human female is born with all the egg cells she will ever have. The possibility for the development of new oocytes is zero. Given this constraint, it is crucial that these gametes remain healthy and viable for decades until they are needed to form an embryo. Irrespective of the ‘age’ of the fertilized oocyte, the resulting embryo has the characteristics of a freshly born cell, indicating the existence of mechanisms that counteract accrued cellular damage and keep the egg fresh. What are these processes that drive the prolonged life of human egg cells? I begin this chapter with three outrageous facts:

I begin this chapter with three outrageous facts: Here’s an old paradox. The scientist declares that science is the only way to truth and that philosophy is bunk. “Over here in my department,” he proclaims, “we really learn things about reality. We poke and prod the universe and see what happens. We formulate hypotheses, design and conduct experiments to test them, analyze the data, and form justified conclusions about the way the world works on that basis. Over in the philosophy department, they don’t do any of that. They make shit up. What I’m doing is REAL and IMPORTANT and GENERATES KNOWLEDGE. Philosophers do none of those things!” And the philosopher, hearing this rant, has a ready reply: “What experiments did you do to establish the truth of that little speech? None at all! (And if you did run an experiment, I’d love to hear about the setup!) Turns out that you’re endorsing a bunch of philosophical claims. So you yourself have a philosophy all your own! Philosophy is inescapable for both of us. The only difference is that I’m honest about it.”

Here’s an old paradox. The scientist declares that science is the only way to truth and that philosophy is bunk. “Over here in my department,” he proclaims, “we really learn things about reality. We poke and prod the universe and see what happens. We formulate hypotheses, design and conduct experiments to test them, analyze the data, and form justified conclusions about the way the world works on that basis. Over in the philosophy department, they don’t do any of that. They make shit up. What I’m doing is REAL and IMPORTANT and GENERATES KNOWLEDGE. Philosophers do none of those things!” And the philosopher, hearing this rant, has a ready reply: “What experiments did you do to establish the truth of that little speech? None at all! (And if you did run an experiment, I’d love to hear about the setup!) Turns out that you’re endorsing a bunch of philosophical claims. So you yourself have a philosophy all your own! Philosophy is inescapable for both of us. The only difference is that I’m honest about it.” Put a bagel in a toaster oven and push a button. In a few seconds, heating elements inside the oven glow red and heat the bagel. The action seems simple — after all, ten-year-olds routinely toast bagels without adult supervision. Matters look different if you inquire into what must happen to make the oven work. Pushing the button engages the mechanism of an incomprehensibly vast multinational network: the North American electrical grid.

Put a bagel in a toaster oven and push a button. In a few seconds, heating elements inside the oven glow red and heat the bagel. The action seems simple — after all, ten-year-olds routinely toast bagels without adult supervision. Matters look different if you inquire into what must happen to make the oven work. Pushing the button engages the mechanism of an incomprehensibly vast multinational network: the North American electrical grid. Zohran Mamdani’s triumph in New York City’s Democratic primary for mayor has forced, among many Jews, a reckoning with how far they have drifted from one another. Mamdani does not use the slogan “globalize the intifada,” but he does not condemn those who do. He has said that if he were mayor, Benjamin Netanyahu, the prime minister of Israel, would face arrest on war crimes charges if he set foot in New York City. Israel has a right to exist, he says, but “as a state with equal rights.”

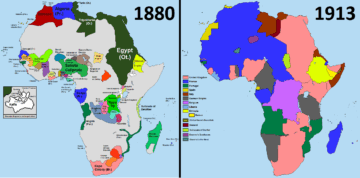

Zohran Mamdani’s triumph in New York City’s Democratic primary for mayor has forced, among many Jews, a reckoning with how far they have drifted from one another. Mamdani does not use the slogan “globalize the intifada,” but he does not condemn those who do. He has said that if he were mayor, Benjamin Netanyahu, the prime minister of Israel, would face arrest on war crimes charges if he set foot in New York City. Israel has a right to exist, he says, but “as a state with equal rights.” The great surprise of the first quarter of the 21st century has been the endurance of Africa’s colonial borders. The durability of Africa’s multiethnic states, most of which project power unevenly over vast territories and possess relatively small militaries, has everything to do with their tradition of multilateralism, a tradition born out of the social networks of anticolonial struggle and the Pan-African Congresses of the first half of the 20th century. Rather than a

The great surprise of the first quarter of the 21st century has been the endurance of Africa’s colonial borders. The durability of Africa’s multiethnic states, most of which project power unevenly over vast territories and possess relatively small militaries, has everything to do with their tradition of multilateralism, a tradition born out of the social networks of anticolonial struggle and the Pan-African Congresses of the first half of the 20th century. Rather than a  Robert Conquest is a man of contradictions: He has been called “a comic poet of genius” and “a love poet of considerable force” – but he made his mark as one of the first to expose the horrors of Stalinist communism.

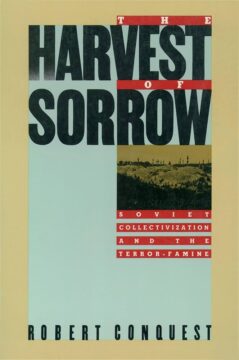

Robert Conquest is a man of contradictions: He has been called “a comic poet of genius” and “a love poet of considerable force” – but he made his mark as one of the first to expose the horrors of Stalinist communism. An antibody treatment developed at Stanford Medicine successfully prepared patients for stem cell transplants without toxic busulfan chemotherapy or radiation, a Phase I clinical trial has shown.

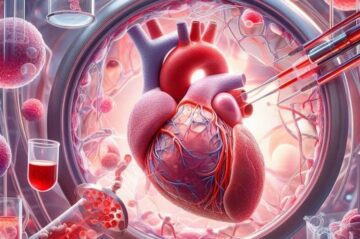

An antibody treatment developed at Stanford Medicine successfully prepared patients for stem cell transplants without toxic busulfan chemotherapy or radiation, a Phase I clinical trial has shown.