Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

The Pictures Of Rosalind Fox Solomon

Christopher Bonanos at Vulture:

Rosalind Fox Solomon has almost never worked on assignment. When she first started taking photographs with an idea of making art, no one would have expected her to turn that into a career; she was heading into her 40s with two children, a woman learning to communicate as she hadn’t been able to before. She started out shooting close to her home in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Even after she started gaining recognition and traveling farther afield, she didn’t exactly have a long-term plan: She would, she says, just decide to go somewhere — occasionally because of a disruptive event, like an earthquake or a flood, but usually just because, hiring a guide and a translator if she needed one. In India, Guatemala, Brazil, or Missouri, she’d move around and look at people, engaging them but not saying much, and come back with pictures. That’s it.

Rosalind Fox Solomon has almost never worked on assignment. When she first started taking photographs with an idea of making art, no one would have expected her to turn that into a career; she was heading into her 40s with two children, a woman learning to communicate as she hadn’t been able to before. She started out shooting close to her home in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Even after she started gaining recognition and traveling farther afield, she didn’t exactly have a long-term plan: She would, she says, just decide to go somewhere — occasionally because of a disruptive event, like an earthquake or a flood, but usually just because, hiring a guide and a translator if she needed one. In India, Guatemala, Brazil, or Missouri, she’d move around and look at people, engaging them but not saying much, and come back with pictures. That’s it.

Did she think about what collectors or publishers or editors might want, the way so many photographers do? “First of all, I’ve never been commercially viable,” Fox Solomon says now. “I never thought about that. Really, I just worked. Piled up my prints, year after year.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Fatal Genius of Shakespeare’s Greatest Rival, Christopher Marlowe

Will Tosh at Literary Review:

Christopher Marlowe is having a moment. In London’s West End, the Royal Shakespeare Company is staging Born with Teeth, a new play by Liz Duffy Adams that imagines the erotic tension crackling between Marlowe and Shakespeare as they collaborate on Henry VI. And right on cue comes the first major biography of Marlowe in two decades, written by the unquestioned eminence of Shakespearean new historicism. This is in some ways a counterpoint to Will in the World, Stephen Greenblatt’s gloriously rich evocation of the early modern culture that nourished Shakespeare’s creative genius. It was Greenblatt more than anyone else who taught us to understand the writer by examining the society in which he or she lived, but in Dark Renaissance the Greenblattian method is turned on its head. He shows us an Elizabethan England altogether too small, bigoted and fearful to account for the emergence of a shooting star like Marlowe.

Christopher Marlowe is having a moment. In London’s West End, the Royal Shakespeare Company is staging Born with Teeth, a new play by Liz Duffy Adams that imagines the erotic tension crackling between Marlowe and Shakespeare as they collaborate on Henry VI. And right on cue comes the first major biography of Marlowe in two decades, written by the unquestioned eminence of Shakespearean new historicism. This is in some ways a counterpoint to Will in the World, Stephen Greenblatt’s gloriously rich evocation of the early modern culture that nourished Shakespeare’s creative genius. It was Greenblatt more than anyone else who taught us to understand the writer by examining the society in which he or she lived, but in Dark Renaissance the Greenblattian method is turned on its head. He shows us an Elizabethan England altogether too small, bigoted and fearful to account for the emergence of a shooting star like Marlowe.

This being Greenblatt, the assertion of inexplicability is a stance. In its sweep, pace and scholarship, the book vividly contextualises Marlowe’s brilliance as a dissident thinker and a wildly innovative writer. Like his exact contemporary Shakespeare, Marlowe’s origins were scrappy. His father was a shoemaker in Canterbury, England’s spiritual capital but a city on its uppers since the eradication of Catholic pilgrimage sites during the early years of the Reformation.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Is Today’s Self-Help Teaching Everyone to Be a Jerk?

Emma Goldberg in The New York Times:

There’s a certain flavor of advice that is dominating the self-help best-seller list. These books have titles like “The Courage to Be Disliked” and “Set Boundaries, Find Peace.” They tell readers not to worry so much about letting people down, not to answer those calls from aggravating friends, not to be afraid of being the villain.

There’s a certain flavor of advice that is dominating the self-help best-seller list. These books have titles like “The Courage to Be Disliked” and “Set Boundaries, Find Peace.” They tell readers not to worry so much about letting people down, not to answer those calls from aggravating friends, not to be afraid of being the villain.

This all becomes more alarming when you think of the best-seller list as a mirror of the social moment, which some historians say it may be.

Take Dale Carnegie’s perma-popular “How to Win Friends and Influence People,” which came out in 1936, meeting readers haunted by memories of bread lines and the slow, dirge-like notes of “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime.” The unemployment rate was at 16.9 percent. Jobs were scarce and financial security was elusive; Mr. Carnegie’s rules for life fell into readers’ hands like manna. Mr. Carnegie promised that some of history’s great men, say Benjamin Franklin and Abraham Lincoln, had achieved success with a formula so simple that it was within anybody’s reach. Placate people. Dole out compliments. “Don’t feel like smiling?” wrote Mr. Carnegie, who had changed his last name’s spelling to match the steel magnate’s, to whom he had no relation. “Force yourself to smile. If you are alone, force yourself to whistle or hum a tune.” (Lincoln’s letters to some generals were apparently heavy on flattery.)

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday, August 31, 2025

The Weaponized World Economy

Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman in Foreign Affairs:

When Washington announced a “framework deal” with China in June, it marked a silent shifting of gears in the global political economy. This was not the beginning of U.S. President Donald Trump’s imagined epoch of “liberation” under unilateral American greatness or a return to the Biden administration’s dream of managed great-power rivalry. Instead, it was the true opening of the age of weaponized interdependence, in which the United States is discovering what it is like to have others do unto it as it has eagerly done unto others.

This new era will be shaped by weapons of economic and technological coercion—sanctions, supply chain attacks, and export measures—that repurpose the many points of control in the infrastructure that underpins the interdependent global economy. For over two decades, the United States has unilaterally weaponized these chokepoints in finance, information flows, and technology for strategic advantage. But market exchange has become hopelessly entangled with national security, and the United States must now defend its interests in a world in which other powers can leverage chokepoints of their own.

That is why the Trump administration had to make a deal with China. Administration officials now acknowledge that they made concessions on semiconductor export controls in return for China’s easing restrictions on rare-earth minerals that were crippling the United States’ auto industry. U.S. companies that provide chip design software, such as Synopsys and Cadence, can once again sell their technology in China. This concession will help the Chinese semiconductor industry wriggle out of the bind it found itself in when the Biden administration started limiting China’s ability to build advanced semiconductors. And the U.S. firm Nvidia can again sell H20 chips for training artificial intelligence to Chinese customers.

In a little-noticed speech in June, Secretary of State Marco Rubio hinted at the administration’s reasoning.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Trump’s Road to Riyadh: The Geopolitics of AI and Energy Infrastructure

Guy Laron in American Affairs:

Something big happened in the Persian Gulf in May 2025. Donald Trump, fresh off one of the most astonishing comebacks in recent political history, hopped from one Arab capital to the next. He was greeted not merely as a visiting head of state but as something like a returning emperor. The images were surreal: camel processions, sword dances, ululating crowds, gleaming skyscrapers, and desert megaprojects rising from the sand like mirages. Even more staggering were the numbers. By the end of his tour of Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, Trump announced that U.S. companies had signed deals worth an eye-watering $2 trillion. This was, by any measure, the sale of the century, crafted by a man who styles himself as the ultimate dealmaker. But what kind of world order was being built in the Gulf, and how did we get here?

To understand what was unfolding in the Gulf, we need to rewind. The deeper logic of this new order wasn’t born in a single summit; it emerged, barely noticed, through a series of seemingly disconnected events over the last two years. The subsequent outbreak of a brief but dramatic shooting war between Israel and Iran—and the U.S. intervention it induced—are not likely to change its overall trajectory and may ultimately function to solidify it.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Lev Menand on Trump’s Attempt to Fire the Fed’s Lisa Cook over at Odd Lots

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Coordinating Tamil Nadu

Mausam Kumar, Benjamin Bradlow, and Vishnu Venugopalan in Phenomenal World:

In a world of geopolitical realignments, Apple has been pursuing a “China plus one” strategy. As the company, like other global corporations, aims to shift its supplier-base away from China, India has emerged as an apparent beneficiary. Over the last few years, a sizable base of Apple suppliers has sprung up in India and a large share of these are based in Tamil Nadu. Apple is not alone in finding the southernmost state in India attractive.

While there remains a debate around the role of manufacturing versus services in India’s economic trajectory, a disaggregated state-level analysis shows signs of resilience and momentum in India’s manufacturing story, shedding light on its distinct subnational geography. Amid India’s grand ambitions for manufacturing growth in the twenty-first century, Tamil Nadu stands out as an outlier. Estimates show that the share of manufacturing in Tamil Nadu’s Gross State Value Addition (GSVA) stands at over 24 percent. Tamil Nadu’s manufacturing prowess is also evident in its share of factories in the country. The Annual Survey of Industries 2022–23 shows that the state is home to over 31,517 factories, accounting for around 16 percent of the national total. Tamil Nadu ranks first in the number of factories in the country, with Gujarat in second, and Maharashtra in third. Out of a total factory employment of 18.5 million, the state accounts for one out of every seven manufacturing jobs in the country.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A Rebel Writer’s First Revolt

Madeline Coleman in Vulture:

Arundhati Roy identifies as a vagrant. There was a moment in 1997, right after the Delhi-based writer became the first Indian citizen to win the Booker Prize, for her best-selling debut, The God of Small Things, when the president and the prime minister claimed the whole country was proud of her. She was 36 and suddenly rich; she could have coasted on the money and praise. Instead, she changed direction. Furiously and at length, she started writing essays for Indian magazines about everything her country’s elites were doing wrong. As nationalists celebrated Indian nuclear tests, she wrote, “The air is thick with ugliness and there’s the unmistakable stench of fascism on the breeze.” In another essay: “On the whole, in India, the prognosis is — to put it mildly — Not Good.” She wrote about Hindu-nationalist violence, military occupation in Kashmir, poverty, displacement, Islamophobia, and corporate crimes. Her anti-patriotic turn got her dragged in the press and then to court on charges that ranged from obscenity (for a cross-caste sex scene in The God of Small Things) to, most recently, terrorism. She began to define herself against the conflict. As Roy writes in Mother Mary Comes to Me, her new memoir, “The more I was hounded as an antinational, the surer I was that India was the place I loved, the place to which I belonged. Where else could I be the hooligan that I was becoming? Where else would I find co-hooligans I so admired?”

Arundhati Roy identifies as a vagrant. There was a moment in 1997, right after the Delhi-based writer became the first Indian citizen to win the Booker Prize, for her best-selling debut, The God of Small Things, when the president and the prime minister claimed the whole country was proud of her. She was 36 and suddenly rich; she could have coasted on the money and praise. Instead, she changed direction. Furiously and at length, she started writing essays for Indian magazines about everything her country’s elites were doing wrong. As nationalists celebrated Indian nuclear tests, she wrote, “The air is thick with ugliness and there’s the unmistakable stench of fascism on the breeze.” In another essay: “On the whole, in India, the prognosis is — to put it mildly — Not Good.” She wrote about Hindu-nationalist violence, military occupation in Kashmir, poverty, displacement, Islamophobia, and corporate crimes. Her anti-patriotic turn got her dragged in the press and then to court on charges that ranged from obscenity (for a cross-caste sex scene in The God of Small Things) to, most recently, terrorism. She began to define herself against the conflict. As Roy writes in Mother Mary Comes to Me, her new memoir, “The more I was hounded as an antinational, the surer I was that India was the place I loved, the place to which I belonged. Where else could I be the hooligan that I was becoming? Where else would I find co-hooligans I so admired?”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A.I. May Be Just Kind of Ordinary

David Wallace-Wells in The New York Times:

In 2023 — just as ChatGPT was hitting 100 million monthly users, with a large minority of them freaking out about living inside the movie “Her” — the artificial intelligence researcher Katja Grace published an intuitively disturbing industry survey that found that one-third to one-half of top A.I. researchers thought there was at least a 10 percent chance the technology could lead to human extinction or some equally bad outcome.

In 2023 — just as ChatGPT was hitting 100 million monthly users, with a large minority of them freaking out about living inside the movie “Her” — the artificial intelligence researcher Katja Grace published an intuitively disturbing industry survey that found that one-third to one-half of top A.I. researchers thought there was at least a 10 percent chance the technology could lead to human extinction or some equally bad outcome.

A couple of years later, the vibes are pretty different. Yes, there are those still predicting rapid intelligence takeoff, along both quasi-utopian and quasi-dystopian paths. But as A.I. has begun to settle like sediment into the corners of our lives, A.I. hype has evolved, too, passing out of its prophetic phase into something more quotidian — a pattern familiar from our experience with nuclear proliferation, climate change and pandemic risk, among other charismatic megatraumas.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday Poem

Now Here Yet

now

sun

scatters

the old gold

of late summer

about the garden.

how lovely

here seems

with all its busyness

and beauty

yet,

the ghost

of a moon hangs

in a blue sky

intense

solitary

aloof.

by Nils Peterson

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, August 29, 2025

AI has passed the aesthetic Turing Test − and it’s changing our relationship with art

Tamilla Triantoro in The Conversation:

Pick up an August 2025 issue of Vogue and you’ll come across an advertisement for the brand Guess featuring a stunning model. Yet tucked away in small print is a startling admission: She isn’t real. She was generated entirely by AI.

Pick up an August 2025 issue of Vogue and you’ll come across an advertisement for the brand Guess featuring a stunning model. Yet tucked away in small print is a startling admission: She isn’t real. She was generated entirely by AI.

For decades, fashion images have been retouched. But this isn’t airbrushing a real person; it’s a “person” created from scratch, a digital composite of data points, engineered to appear as a beautiful woman.

The backlash to the Guess ad was swift. Veteran model Felicity Hayward called the move “lazy and cheap,” warning that it undermines years of work to promote diversity. After all, why hire models of different sizes, ages and ethnicities when a machine can generate a narrow, market-tested ideal of beauty on demand?

I study human-AI collaboration, and my work focuses on how AI influences decision-making, trust and human agency, all of which came into play during the Vogue controversy.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The gene from Denisovan to Neanderthal to modern mucus

John Hawks at his own website:

On the long arm of chromosome 12 is a gene called MUC19. It’s one of a family of genes that encode proteins called mucins, which provide mucus and mucus membranes their slippery, gelatinous consistency.

On the long arm of chromosome 12 is a gene called MUC19. It’s one of a family of genes that encode proteins called mucins, which provide mucus and mucus membranes their slippery, gelatinous consistency.

Some people have a haplotype spanning part of this gene that came into present-day populations from archaic ancestors. Two of the known Neanderthal genomes, from Vindija and Chagyrskaya, each have copies of a very similar haplotype. So does the Denisova 3 genome.

The story of MUC19 has been uncovered by Fernando Villanea and coworkers, in a preprint that they released last year, and now published in Science. From the sequence of mutational and recombinational changes to the haplotype, they worked out that the gene started in Denisovans, introgressed into late Neanderthals, and from them into modern people.

It’s a game of genetic telephone.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Why the Historical Jesus Matters

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Genie 3: An infinite world model, with Shlomi Fruchter and Jack Parker-Holder

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Orgasm Expert Who Ended Up on Trial

Thessaly La Force at The New Yorker:

The idea for OneTaste took root in 1998, after Daedone met a sexuality coach named Erwan Davon at a party. In her retellings, Daedone has described Davon as a Buddhist monk. (Davon has said he’s spent time living in a Zen monastery.) That night, he offered to stroke her clitoris. He examined her vagina under a light, and began to narrate its colors and shape: coral, rose, pearl pink. Daedone wept. In a TEDxSF talk, from 2011, she describes what happened next: “And then, all of a sudden, the traffic jam that was my mind broke open, and it was like I was on the open road and there was not a thought in sight. And there was only pure feeling, and for the first time in my life I felt like I had access to that hunger that was underneath all of my other hungers, which is a fundamental hunger to connect with another human being.”

The practice, which was called “deliberate orgasm,” originated with Morehouse, a commune—founded in 1968 in Oakland, California—whose goal was to live pleasurably among friends. It was inspired by the life-style and teachings of Victor Baranco, who, in 1971, described himself in Rolling Stone as a former used-car salesman and a “peddler of phony jewelry.” Baranco once held a three-hour demonstration of a deliberate orgasm (including cigarette breaks) with a twenty-two-year-old Morehouse resident named Diana.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

America is run by lawyers, and China is run by engineers

Noah Smith at Noahpinion:

There was a time in 2016 when I walked around downtown San Francisco with Dan Wang and gave him life advice. He asked me if he should move to China and write about it. I told him that I thought this was a good idea — that the world suffered from a strange and troubling dearth of people who write informatively about China in English, and that our country would be better off if we could understand China a little more.

There was a time in 2016 when I walked around downtown San Francisco with Dan Wang and gave him life advice. He asked me if he should move to China and write about it. I told him that I thought this was a good idea — that the world suffered from a strange and troubling dearth of people who write informatively about China in English, and that our country would be better off if we could understand China a little more.

Dan took my advice, and I’m very glad he did. For seven years, Dan wrote some of the best posts about China anywhere on the English-speaking internet, mostly in the form of a series of annual letters. His unique writing style is both lush and subtle. Each word or phrase feels like it should be savored, like fine dining. But don’t let this distract you — there are a multitude of small but important points buried in every paragraph. Dan Wang’s writing cannot be skimmed.

I’ve been anticipating Dan’s first book for over a year now, and it didn’t disappoint. Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future brings the same style Dan used in his annual letters, and uses it to elucidate a grand thesis: America is run by lawyers, and China is run by engineers.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

William Goldman’s Magical Pessimism

Tom Bissell at VQR:

William Goldman wasn’t a great writer, at least not according to traditional standards. His prose, at its best, was like a milkshake: fast and tasty, with the occasional clog. At its worst, his prose could be both chatty and flat, which, like being interestingly dull, is hard to pull off. Goldman was famous for his writing speed, knocking out novels in just weeks. He was equally famous—or, rather, infamous—for his aversion to rewriting. But there has never been another writer quite like him.

William Goldman wasn’t a great writer, at least not according to traditional standards. His prose, at its best, was like a milkshake: fast and tasty, with the occasional clog. At its worst, his prose could be both chatty and flat, which, like being interestingly dull, is hard to pull off. Goldman was famous for his writing speed, knocking out novels in just weeks. He was equally famous—or, rather, infamous—for his aversion to rewriting. But there has never been another writer quite like him.

He began his career with a bildungsroman called The Temple of Gold, which, at twenty-four, he wrote with what he later described as “wild desperation” over three weeks in 1956. It was published the following year by Knopf, a firm looking to capitalize on the Salinger-spawned craze for young, disaffected (and, needless to say, exclusively male) voices. In other words, a more-or-less normal beginning to a mid-century literary career. Goldman did, in fact, write more literary novels—a book a year, for some stretches—including one, Boys and Girls Together, that sold a million copies in paperback. Later, in the 1970s, he began to publish a variety of high-concept thrillers, some stylish and gripping and others, well, dreadful.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Love’s Labour by – the truth about relationships

Sophie McBain in The Guardian:

A maths lecturer, convinced his wife is cheating, will not check the CCTV footage that might confirm his fears but instead keeps a private tally of the number of pubic hairs she sheds in her underwear. One hair is “OK, acceptable”, more is evidence that she has been “having it off”, he says, unaware that he uses these delusions of her infidelity to protect himself from the dangers of intimacy. A high-flying Fulbright scholar becomes a sex worker to avenge the father she hates. An ex-nun discovers that her decades of religious seclusion were driven by an unconscious fear of pregnancy. A troubled young woman, seeking redress for her psychological losses, steals large sums of money that she will never spend.

A maths lecturer, convinced his wife is cheating, will not check the CCTV footage that might confirm his fears but instead keeps a private tally of the number of pubic hairs she sheds in her underwear. One hair is “OK, acceptable”, more is evidence that she has been “having it off”, he says, unaware that he uses these delusions of her infidelity to protect himself from the dangers of intimacy. A high-flying Fulbright scholar becomes a sex worker to avenge the father she hates. An ex-nun discovers that her decades of religious seclusion were driven by an unconscious fear of pregnancy. A troubled young woman, seeking redress for her psychological losses, steals large sums of money that she will never spend.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

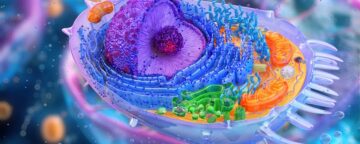

Protein Evolution in Mammalian Cells May Improve Therapeutics

Andrea Lius in The Scientist:

To develop better protein-based drugs, scientists can force these molecules to evolve in the lab within a much-shortened time scale. Due to technical limitations, this synthetic biology approach, collectively known as directed evolution, mostly relies on single-celled organisms, such as bacteria or yeast, even when the end-products are intended for humans.1 However, because the intracellular environments of mammalian cells are dramatically different from those of bacteria and yeast, this compromise often leads to the production of nonfunctional proteins, which defeats the very purpose of directed evolution.

To develop better protein-based drugs, scientists can force these molecules to evolve in the lab within a much-shortened time scale. Due to technical limitations, this synthetic biology approach, collectively known as directed evolution, mostly relies on single-celled organisms, such as bacteria or yeast, even when the end-products are intended for humans.1 However, because the intracellular environments of mammalian cells are dramatically different from those of bacteria and yeast, this compromise often leads to the production of nonfunctional proteins, which defeats the very purpose of directed evolution.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.