James Parker in The Atlantic:

“Pretty good nose you got there! You do much fighting with that nose?”

“Pretty good nose you got there! You do much fighting with that nose?”

New Orleans, 1989. I’m standing on a balcony south of the Garden District, and a man—a stranger—is hailing me from the street. He looks like Paul Newman, if Paul Newman were an alcoholic housepainter. I don’t, as it happens, do much fighting with this nose, but that’s not the point. The point is that something about me, the particular young-man way I’m jutting into the world—physically, attitudinally, beak first—is being recognized. The actual contour of me, or so I feel, is being saluted. For the first time.

America, this is personal. I came to you as a cramped and nervous Brit, an overwound piece of English clockwork, and you laid your cities before me. The alcoholic housepainter gave me a job, and it worked out pretty much as you might expect, given that I had never painted houses before and he was an alcoholic. Nonetheless, I was at large. I was in American space. I could feel it spreading away unsteadily on either side of me: raw innocence, potential harm, beckoning peaks, buzzing ions of possibility, and threading through it, in and out of range, fantastic, dry-bones laughter. No safety net anywhere, but rather—if I could only adjust myself to it, if I could be worthy of it—a crackling, sustaining buoyancy.

I blinked, and the baggage of history fell off me. Neurosis rolled down the hill. (It rolled back up later, but that’s another story.) America, it’s true what they say about you—all the good stuff. I’d be allowed to do something here. I’d be encouraged to do something here. It would be demanded of me, in the end, that I do something here.

Later that year I’m in San Francisco, ripping up the carpets in someone’s house. Sweaty work. Fun work, if you don’t have to do it all the time: I love the unzipping sound of a row of carpet tacks popping out of a hardwood floor.

More here.

In this book, she explores the history of intellectual discussions of pantheism, and raises questions about why so many Western philosophers and theologians have resisted this concept. Pantheism is combined of two Greek words, pan—which means ‘all’—and theism, which consists of belief in God. Here All is God, or God is All. In most of Western thought, pantheism functions as a limit concept. That is, if we want to think about or have faith in a divinity, it needs to be related to the world, the all or everything, but pantheism names the collapse of this God into everything else to the extent that there is nothing that is not God.

In this book, she explores the history of intellectual discussions of pantheism, and raises questions about why so many Western philosophers and theologians have resisted this concept. Pantheism is combined of two Greek words, pan—which means ‘all’—and theism, which consists of belief in God. Here All is God, or God is All. In most of Western thought, pantheism functions as a limit concept. That is, if we want to think about or have faith in a divinity, it needs to be related to the world, the all or everything, but pantheism names the collapse of this God into everything else to the extent that there is nothing that is not God.

If you’re wondering whether we’ll do anything about global warming before it destroys civilization, think about this ominous fact: It occupies barely any space in popular culture.

If you’re wondering whether we’ll do anything about global warming before it destroys civilization, think about this ominous fact: It occupies barely any space in popular culture. Researchers with the

Researchers with the  “P

“P The

The

Don Quixote is the Saturday Night Live of the Spanish Inquisition. Cervantes roasts everybody, including the Catholic Church and even the reader. This magnum opus—called by many the first Western novel—is really a book about reading: Carlos Fuentes famously said of Quixote: “Su lectura es su locura.” [“His reading is his madness.”] Quixote reads too much (if that’s possible) and wants to become the literary heroes of his books. But just who are those heroes?

Don Quixote is the Saturday Night Live of the Spanish Inquisition. Cervantes roasts everybody, including the Catholic Church and even the reader. This magnum opus—called by many the first Western novel—is really a book about reading: Carlos Fuentes famously said of Quixote: “Su lectura es su locura.” [“His reading is his madness.”] Quixote reads too much (if that’s possible) and wants to become the literary heroes of his books. But just who are those heroes? IN OSAKA, JAPAN,

IN OSAKA, JAPAN, In advanced economies, earnings for those with less education often stagnated despite gains in overall labor productivity. Since 1979, for example, US production workers’ compensation has risen by

In advanced economies, earnings for those with less education often stagnated despite gains in overall labor productivity. Since 1979, for example, US production workers’ compensation has risen by  There have been many English Baudelaires through the 150 years since his death, two dozen reasonably ample selected poems, and a dozen or so Les Fleurs du mal (a new one arrives next month, translated by

There have been many English Baudelaires through the 150 years since his death, two dozen reasonably ample selected poems, and a dozen or so Les Fleurs du mal (a new one arrives next month, translated by  Religion and sincerity go hand in hand, and neither one is particularly associated with Andy Warhol, whose name is synonymous with ironic, detached irreverence. But you don’t have to dig very deep in Warhol’s biography or catalog to find plenty of both. Warhol was Byzantine Catholic, a denomination combining aspects of both Western and Eastern rites. He went to church with his mother almost every Sunday until her death in 1974 and attended regularly in the years after. One of his last diary entries, two months before his death, records that he “went to the Church of Heavenly Rest to pass out Interviews and feed the poor.” It’s impossible to know for sure where the limit of irony lies with an artist like Warhol; maybe he went to Church as a bit. But his deep superstitions and his fear of dying, at least, seem to have been very real, even before he was nearly assassinated.

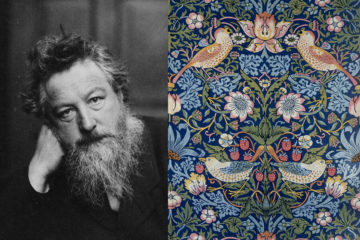

Religion and sincerity go hand in hand, and neither one is particularly associated with Andy Warhol, whose name is synonymous with ironic, detached irreverence. But you don’t have to dig very deep in Warhol’s biography or catalog to find plenty of both. Warhol was Byzantine Catholic, a denomination combining aspects of both Western and Eastern rites. He went to church with his mother almost every Sunday until her death in 1974 and attended regularly in the years after. One of his last diary entries, two months before his death, records that he “went to the Church of Heavenly Rest to pass out Interviews and feed the poor.” It’s impossible to know for sure where the limit of irony lies with an artist like Warhol; maybe he went to Church as a bit. But his deep superstitions and his fear of dying, at least, seem to have been very real, even before he was nearly assassinated. Behind the exquisite floral wallpaper lurks a social reformer. British designer William Morris (1834-96) is today best known for his lush, garden-inspired patterns for wall coverings, but his lifework encompassed far more than mere decoration. He sought nothing less than to overturn what he considered the deleterious effects of industrialization on Victorian society. And his artistic influence continues today, not only at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, an institution he helped shape, but also as inspiration to contemporary artists.

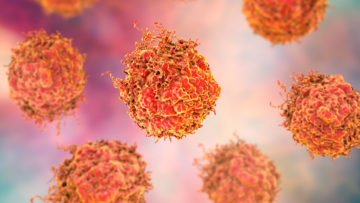

Behind the exquisite floral wallpaper lurks a social reformer. British designer William Morris (1834-96) is today best known for his lush, garden-inspired patterns for wall coverings, but his lifework encompassed far more than mere decoration. He sought nothing less than to overturn what he considered the deleterious effects of industrialization on Victorian society. And his artistic influence continues today, not only at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, an institution he helped shape, but also as inspiration to contemporary artists. Underground creepy crawly state. Bosom malignancy. Sun oriented force. These might sound like expressions from a work of fiction, but they are actually strange translations, pulled from the scholarly literature, of scientific terms — ant colony, breast cancer and solar energy, respectively. Guillaume Cabanac, a computer scientist at the University of Toulouse, France, spots such bizarre phrases in academic papers every day.

Underground creepy crawly state. Bosom malignancy. Sun oriented force. These might sound like expressions from a work of fiction, but they are actually strange translations, pulled from the scholarly literature, of scientific terms — ant colony, breast cancer and solar energy, respectively. Guillaume Cabanac, a computer scientist at the University of Toulouse, France, spots such bizarre phrases in academic papers every day. About 30 minutes into his new concert film Blackalachia,

About 30 minutes into his new concert film Blackalachia,