Nathan Heller in The New Yorker:

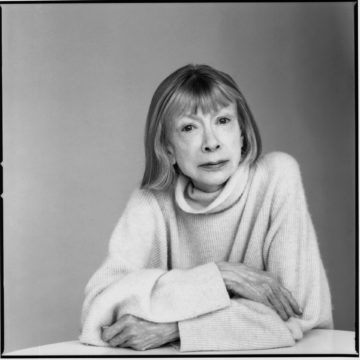

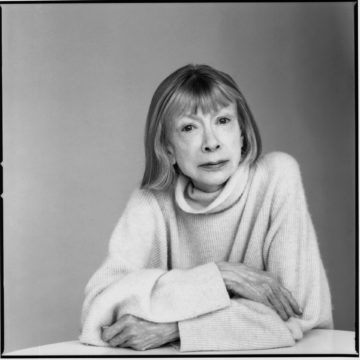

When Joan Didion died, on Thursday, at eighty-seven, she left behind sixteen books, seven films, one play, and an impulse to make sense of what remained. It was tempting to note that, like her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne, whose passing shaped “The Year of Magical Thinking” (2005), she died during the Christmas holiday. It was easy to see, as she did in her daughter’s lethal illness that same season, larger gears at work. Didion was a pattern-seeker—a writer with an uncanny ability to scan a text, a folder of clippings, or an entire society and, like a genius eying figures, find the markers pointing out how the whole worked. Through her efforts, the craft of journalism changed. She helped expand the landscape of what matters on the page.

When Joan Didion died, on Thursday, at eighty-seven, she left behind sixteen books, seven films, one play, and an impulse to make sense of what remained. It was tempting to note that, like her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne, whose passing shaped “The Year of Magical Thinking” (2005), she died during the Christmas holiday. It was easy to see, as she did in her daughter’s lethal illness that same season, larger gears at work. Didion was a pattern-seeker—a writer with an uncanny ability to scan a text, a folder of clippings, or an entire society and, like a genius eying figures, find the markers pointing out how the whole worked. Through her efforts, the craft of journalism changed. She helped expand the landscape of what matters on the page.

Though Didion spent half her life in New York (first as a junior editor at Vogue, then, in a later stint, as a short-statured lioness of letters), much of her best-known work was done in California, where she’d grown up in mid-century Sacramento. Her ominous, valley-flat style channelled the Pacific terrain, with its beauty and severity and restless turns. “This is the country in which a belief in the literal interpretation of Genesis has slipped imperceptibly into a belief in the literal interpretation of Double Indemnity, the country of the teased hair and the Capris and the girls for whom all life’s promise comes down to a waltz-length white wedding dress and the birth of a Kimberly or a Sherry or a Debbi and a Tijuana divorce and a return to hairdressers’ school,” she wrote in “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream,” the essay that opened her first collection, “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” (1968). That book announced her subject—the long, crazed shadow of the frontier mentality—and her style, which carried across five novels and several screenplays, not least “A Star Is Born” (1976), which she co-wrote with Dunne. Today, readers know what’s meant by “Didionesque.”

Like most strong stylists, though, Didion worked up her craft as a sensitive reader of other masters. She had been an English student, at Berkeley, in the nineteen-fifties, a high point for the New Criticism and its close reading, and the approach became part of her lifelong methodology, applied equally to language she encountered as a reporter and to literary work. In a New Yorker essay about Hemingway, her early influence, she performed an unmatched reading of the beginning of “A Farewell to Arms,” noting how the sudden, pattern-breaking absence of a “the” before the third appearance of “leaves” casts “exactly what it was meant to cast, a chill, a premonition.” It was characteristic of Didion to work this way, in the danger zone between sensibility and objectivity: to be receptive to a passing feeling, a change in cast, and then to bear down, with unsparing rigor, in the work of understanding why.

More here.

If the authentic test for a great novel is rereading, and the joys of yet further rereadings, then Pride and Prejudice can rival any novel ever written. Though Jane Austen, unlike Shakespeare, practices an art of rigorous exclusion, she seems to me finally the most Shakespearean novelist in the language. When Shakespeare wishes to, he can make all his personages, major and minor, speak in voices entirely their own, self-consistent and utterly different from one another. Austen, with the similar illusion of ease, does the same. Since voice in both writers is an image of personality and also of character, the reader of Austen encounters an astonishing variety of selves in her socially confined world. Though that world is essentially a secularized culture, the moral vision dominating it remains that of the Protestant sensibility.

If the authentic test for a great novel is rereading, and the joys of yet further rereadings, then Pride and Prejudice can rival any novel ever written. Though Jane Austen, unlike Shakespeare, practices an art of rigorous exclusion, she seems to me finally the most Shakespearean novelist in the language. When Shakespeare wishes to, he can make all his personages, major and minor, speak in voices entirely their own, self-consistent and utterly different from one another. Austen, with the similar illusion of ease, does the same. Since voice in both writers is an image of personality and also of character, the reader of Austen encounters an astonishing variety of selves in her socially confined world. Though that world is essentially a secularized culture, the moral vision dominating it remains that of the Protestant sensibility.

When Joan Didion died, on Thursday, at eighty-seven, she left behind sixteen books, seven films, one play, and an impulse to make sense of what remained. It was tempting to note that, like her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne, whose passing shaped “

When Joan Didion died, on Thursday, at eighty-seven, she left behind sixteen books, seven films, one play, and an impulse to make sense of what remained. It was tempting to note that, like her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne, whose passing shaped “ Joan Didion, whose mordant dispatches on California culture and the chaos of the 1960s established her as a leading exponent of the New Journalism, and whose novels “Play It as It Lays” and “A Book of Common Prayer” proclaimed the arrival of a tough, terse, distinctive voice in American fiction, died on Thursday at her home in Manhattan. She was 87.

Joan Didion, whose mordant dispatches on California culture and the chaos of the 1960s established her as a leading exponent of the New Journalism, and whose novels “Play It as It Lays” and “A Book of Common Prayer” proclaimed the arrival of a tough, terse, distinctive voice in American fiction, died on Thursday at her home in Manhattan. She was 87. In my previous

In my previous  The discovery of a Standard Model-like Higgs boson was a great triumph for renormalisable field theory, and really for simplicity. By the time the LHC was operating, attempts to make the Standard Model (SM) work without an elementary Higgs field – using a dynamical mechanism instead – had become rather convoluted. It turned out that, as far as one can judge from what we have learned so far, the original idea of an elementary Higgs particle was correct. This also means that nature takes advantage of all the possible building blocks of renormalisable field theory – fields of spin 0, 1/2 and 1 – and the flexibility that that allows.

The discovery of a Standard Model-like Higgs boson was a great triumph for renormalisable field theory, and really for simplicity. By the time the LHC was operating, attempts to make the Standard Model (SM) work without an elementary Higgs field – using a dynamical mechanism instead – had become rather convoluted. It turned out that, as far as one can judge from what we have learned so far, the original idea of an elementary Higgs particle was correct. This also means that nature takes advantage of all the possible building blocks of renormalisable field theory – fields of spin 0, 1/2 and 1 – and the flexibility that that allows. The popular narrative goes that history is governed by evolutionary forces. While there are exceptions to every rule, its broad sweep pushes in a general direction that is predictable and obvious. Before the rise of agriculture, humans lived in small egalitarian bands. It’s been downhill ever since, as our species trends increasingly toward domination and arbitrary hierarchy.

The popular narrative goes that history is governed by evolutionary forces. While there are exceptions to every rule, its broad sweep pushes in a general direction that is predictable and obvious. Before the rise of agriculture, humans lived in small egalitarian bands. It’s been downhill ever since, as our species trends increasingly toward domination and arbitrary hierarchy. It’s Christmas in Paris and Les Champs-Elysees is appropriately adorned. We are, after all, in the so-called Elysian Fields, paradise, heaven on earth. Red illuminated trees line both side of France’s most famous avenue, stars fill the sky and the red carpet is laid out in front of the prestigious Gaumont cinema. The welcome is fit for royalty. And, on cue, Jesus turns up.

It’s Christmas in Paris and Les Champs-Elysees is appropriately adorned. We are, after all, in the so-called Elysian Fields, paradise, heaven on earth. Red illuminated trees line both side of France’s most famous avenue, stars fill the sky and the red carpet is laid out in front of the prestigious Gaumont cinema. The welcome is fit for royalty. And, on cue, Jesus turns up. I’ve begun to fear that requiring my existentialism students to bring real books to class is . . . well, absurd. Absurd not just in the everyday sense of ridiculous, but absurd in the Camusian sense as well. Is it just as unreasonable to demand that students use an ancient technology as it is to demand that an indifferent universe offers us meaning? It might be the case that my traditional expectations of students are unreasonable. More than a few students, rather than bringing paperbacks of the assigned works, bring printouts. At best, this means they haven’t the means to buy the book; at worst, it means they find unmeaningful the very possession of the book. They have no more intention to keep a printout—to reread or reflect upon it—than I have the intention to keep yesterday’s newspaper.

I’ve begun to fear that requiring my existentialism students to bring real books to class is . . . well, absurd. Absurd not just in the everyday sense of ridiculous, but absurd in the Camusian sense as well. Is it just as unreasonable to demand that students use an ancient technology as it is to demand that an indifferent universe offers us meaning? It might be the case that my traditional expectations of students are unreasonable. More than a few students, rather than bringing paperbacks of the assigned works, bring printouts. At best, this means they haven’t the means to buy the book; at worst, it means they find unmeaningful the very possession of the book. They have no more intention to keep a printout—to reread or reflect upon it—than I have the intention to keep yesterday’s newspaper. Although the jungles of southern Mexico seem like an ideal spot for fieldwork, the region’s sulfur springs are far from a tropical getaway. In addition to the area’s stifling heat, the pools reek of rotten eggs. Their milky, turquoise water is even more inhospitable: it is laced with toxic levels of hydrogen sulfide and contains very little oxygen.

Although the jungles of southern Mexico seem like an ideal spot for fieldwork, the region’s sulfur springs are far from a tropical getaway. In addition to the area’s stifling heat, the pools reek of rotten eggs. Their milky, turquoise water is even more inhospitable: it is laced with toxic levels of hydrogen sulfide and contains very little oxygen. B

B George Steiner was called many things across his lengthy writing career—sage, pedant, philosopher, snob, the last great European intellectual, a “mimic” staging a decades-long “impression of the world’s most learned man”—but the title he always claimed for himself was simply critic. As we reflect on the meaning of Steiner’s work in the wake of his death in February 2020, that self-characterization cannot be forgotten. Steiner was in many ways a formidable scholar, and his commentaries on core texts (Antigone, The Brothers Karamazov, the poetry of Paul Celan) and enduring themes (tragedy, translation, the inhuman) will surely be cited for many years to come. Yet from the beginning of his career in the late fifties to his last notable works at the turn of the century, he was explicitly engaged in the practice of criticism—the goal of which was to reach the wider republic of readers (not just academicians) with his urgent dispatches on the state of the arts and culture. It was as a critic that he asked to be judged.

George Steiner was called many things across his lengthy writing career—sage, pedant, philosopher, snob, the last great European intellectual, a “mimic” staging a decades-long “impression of the world’s most learned man”—but the title he always claimed for himself was simply critic. As we reflect on the meaning of Steiner’s work in the wake of his death in February 2020, that self-characterization cannot be forgotten. Steiner was in many ways a formidable scholar, and his commentaries on core texts (Antigone, The Brothers Karamazov, the poetry of Paul Celan) and enduring themes (tragedy, translation, the inhuman) will surely be cited for many years to come. Yet from the beginning of his career in the late fifties to his last notable works at the turn of the century, he was explicitly engaged in the practice of criticism—the goal of which was to reach the wider republic of readers (not just academicians) with his urgent dispatches on the state of the arts and culture. It was as a critic that he asked to be judged. IN DRESDEN, a city renowned for the picture-perfect restoration by which it looks the same and yet entirely strange, an old tale of love and deception is playing out.

IN DRESDEN, a city renowned for the picture-perfect restoration by which it looks the same and yet entirely strange, an old tale of love and deception is playing out.

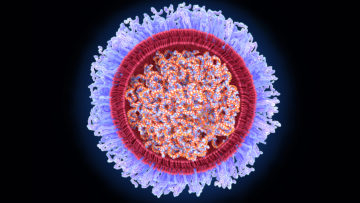

Tiny molecules came up big in 2021. By year’s end, COVID-19 vaccines based on snippets of mRNA, or messenger RNA, proved to be safe and incredibly effective at preventing the worst outcomes of the disease.

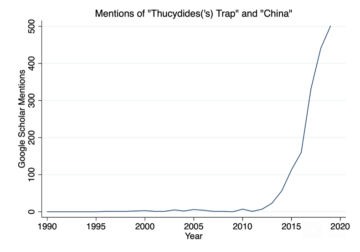

Tiny molecules came up big in 2021. By year’s end, COVID-19 vaccines based on snippets of mRNA, or messenger RNA, proved to be safe and incredibly effective at preventing the worst outcomes of the disease. When I discuss the US-China relationship with people, I’ve found that they often turn to the concept of the “Thucydides Trap.” It seems as if few international relations books in the last decade have had as much influence as

When I discuss the US-China relationship with people, I’ve found that they often turn to the concept of the “Thucydides Trap.” It seems as if few international relations books in the last decade have had as much influence as  William Hasselberger,

William Hasselberger,