Category: Recommended Reading

On Lice

AK Blakemore at Granta:

With all due respect, lice and fleas have changed the world more than you ever have, or will, reader. They are part of the unwitting ensemble cast of human history, like Alexander the Great’s Bucephalus, or Karl Lagerfeld’s Choupette. This is because they are now understood to be ‘vectors of disease’, making other bodies’ business your own. But even before this was properly understood, their reputation wasn’t great.

With all due respect, lice and fleas have changed the world more than you ever have, or will, reader. They are part of the unwitting ensemble cast of human history, like Alexander the Great’s Bucephalus, or Karl Lagerfeld’s Choupette. This is because they are now understood to be ‘vectors of disease’, making other bodies’ business your own. But even before this was properly understood, their reputation wasn’t great.

Galileo was probably the first person to see into a flea’s face. While modifying the compound telescope that would situate humanity in a universe that frankly didn’t care for it very much, he fucked around and invented a compound microscope as well. ‘I have observed many tiny animals with great admiration’, he wrote, ‘among which the flea is quite horrible’.

more here.

Webb telescope blasts off successfully — launching a new era in astronomy

Alexandra Witze in Nature:

The James Webb Space Telescope — humanity’s biggest gamble yet in its quest to probe the Universe — soared into space on 25 December, marking the culmination of decades of work by astronomers around the world. But for Webb to begin a new era in astronomy, as many scientists hope it will, hundreds of complex engineering steps will have to go off without a hitch in the coming days and weeks. “Now the hard part starts,” says John Grunsfeld, an astrophysicist and former astronaut and head of science for NASA.

The James Webb Space Telescope — humanity’s biggest gamble yet in its quest to probe the Universe — soared into space on 25 December, marking the culmination of decades of work by astronomers around the world. But for Webb to begin a new era in astronomy, as many scientists hope it will, hundreds of complex engineering steps will have to go off without a hitch in the coming days and weeks. “Now the hard part starts,” says John Grunsfeld, an astrophysicist and former astronaut and head of science for NASA.

The US$10-billion Webb is the most complicated and expensive space observatory in history, and the successor to NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, which has studied the Universe since 1990. Following its launch, Webb will now embark on the riskiest part of its mission — deploying all the parts required for its enormous mirror to peer deep into the cosmos, back towards the dawn of time.

Not until all the equipment works and the first scientific observations have been made, likely in July, will astronomers be able to relax. Until then, “there’s going to be a lot of nervousness”, says Heidi Hammel, an interdisciplinary scientist for Webb and vice-president for science at the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy in Washington DC. The NASA-built Webb launched at 9:20 a.m. local time from the Kourou spaceport in French Guiana, on an Ariane 5 rocket provided by the European Space Agency (ESA). The project’s third international partner is the Canadian Space Agency.

More here.

It’s Time for Some Game Theory

Caroline Wazer in Lapham’s Quarterly:

In March 2021 the American Historical Review included three video games in its review section, a first for the self-proclaimed “journal of record for the historical profession in the United States.” All three games selected for review are installments of the Assassin’s Creed franchise, which takes as its central conceit a centuries-long struggle between two shadowy organizations: the Templars, who seek to control and manipulate humanity for their own ends, and the Assassins, who champion human freedom and creativity and are usually (though not always) cast as morally superior. Throughout the franchise players are tapped by one or both factions to hunt for powerful artifacts called Pieces of Eden, each of which was hidden or lost long ago. Finding these artifacts requires accessing the past by means of a fictional technology called the Animus, which generates lifelike, interactive virtual-reality worlds from ancient DNA samples taken from the remains of long-dead witnesses to the Pieces of Eden’s fates.

In March 2021 the American Historical Review included three video games in its review section, a first for the self-proclaimed “journal of record for the historical profession in the United States.” All three games selected for review are installments of the Assassin’s Creed franchise, which takes as its central conceit a centuries-long struggle between two shadowy organizations: the Templars, who seek to control and manipulate humanity for their own ends, and the Assassins, who champion human freedom and creativity and are usually (though not always) cast as morally superior. Throughout the franchise players are tapped by one or both factions to hunt for powerful artifacts called Pieces of Eden, each of which was hidden or lost long ago. Finding these artifacts requires accessing the past by means of a fictional technology called the Animus, which generates lifelike, interactive virtual-reality worlds from ancient DNA samples taken from the remains of long-dead witnesses to the Pieces of Eden’s fates.

Despite the fantastic silliness of the in-game time-travel logistics, the promise of historical accuracy has been a major selling point of Assassin’s Creed since the eponymous first installment in 2007; since then Ubisoft, its publisher, reports having sold more than 155 million units of the franchise, which has grown to include a total of twelve main games (the most recent being 2020’s Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla, which takes place mostly in Viking-age England). “Assassin’s Creed is steeped in historical fact,” a video-game reviewer for IGN writes of the first game in the series, which is set primarily in the twelfth-century Holy Land. “Were it not for the ‘anomalies’ that flitter around characters”—part of the sci-fi wrapping—“you would have little reason to ever question that this is indeed what these cities and people looked like centuries ago.”

In the first of the AHR reviews, historian of early America Michael D. Hattem gives a positive assessment of Assassin’s Creed III (2012), praising the verisimilitude of its Revolutionary War–era colonial American setting as well as the way the game emphasizes social history. “The attention paid by the game developers and their historical consultants to details of both the actual and social geography of these urban settings,” he writes, “produced one of the most authentic depictions of eighteenth-century life in popular culture”—far more historically accurate, he adds, than Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Broadway musical Hamilton. Video games like this, Hattem concludes, are “ideally situated as a cultural form to tell the kind of complex story of the Revolution reflected in recent academic scholarship.”

More here.

Wednesday, December 29, 2021

Must we find our future in the past? Kwame Anthony Appiah on David Graeber and David Wengrow’s book “The Dawn of Everything”

Kwame Anthony Appiah in the New York Review of Books:

That the history of our species came in stages was an idea that came in stages. Aristotle saw the formation of political entities as a tripartite process: first we had families; next we had the villages into which they banded; and finally, in the coalescence of those villages, we got a governed society, the polis. Natural law theorists later offered fable-like notions of how politics arose from the state of nature, culminating in Thomas Hobbes’s mid-seventeenth-century account of how the sovereign rescued prepolitical man from a ceaseless war of all against all.

But it was Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a hundred years later, who popularized the idea that we could peer at our prehistory and discern developmental stages marked by shifts in technology and social arrangements.

More here.

Researchers uncover a single rule for how animals make spatial decisions while on the move

From the Max Planck Gesellschaft:

An international team led by researchers from the University of Konstanz and Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior in Germany have employed virtual reality to decode the algorithm that animals use when deciding where to go among many options. The study reveals that animals cope with environmental complexity by reducing the world into a series of sequential two-choice (binary) decisions — a strategy that results in highly effective decision-making no matter how many options there are. The study offers the first evidence yet of a common algorithm that governs decision-making across species and suggests that fundamental geometric principles can explain how, and why, animals move the way they do.

An international team led by researchers from the University of Konstanz and Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior in Germany have employed virtual reality to decode the algorithm that animals use when deciding where to go among many options. The study reveals that animals cope with environmental complexity by reducing the world into a series of sequential two-choice (binary) decisions — a strategy that results in highly effective decision-making no matter how many options there are. The study offers the first evidence yet of a common algorithm that governs decision-making across species and suggests that fundamental geometric principles can explain how, and why, animals move the way they do.

More here.

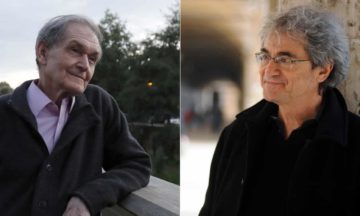

Nobel laureates call for 2% cut to military spending worldwide

Dan Sabbagh in The Guardian:

More than 50 Nobel laureates have signed an open letter calling for all countries to cut their military spending by 2% a year for the next five years, and put half the saved money in a UN fund to combat pandemics, the climate crisis, and extreme poverty.

More than 50 Nobel laureates have signed an open letter calling for all countries to cut their military spending by 2% a year for the next five years, and put half the saved money in a UN fund to combat pandemics, the climate crisis, and extreme poverty.

Coordinated by the Italian physicist Carlo Rovelli, the letter is supported by a large group of scientists and mathematicians including Sir Roger Penrose, and is published at a time when rising global tensions have led to a steady increase in arms budgets.

“Individual governments are under pressure to increase military spending because others do so,” the signatories say in support of the newly launched Peace Dividend campaign. “The feedback mechanism sustains a spiralling arms race – a colossal waste of resources that could be used far more wisely.”

More here.

Why You Should Want Driverless Cars On Roads Now

One Of The Great Whodunnits Of Art History

Martin Gayford at The Spectator:

On 25 October 1510 Isabella d’Este, the Marchioness of Mantua, wrote a letter to her agent in Venice inquiring after a certain highly collectable item. ‘We believe that in the effects and the estate of Zorzo da Castelfranco, the painter, there exists a painting of a night scene, very beautiful and unusual.’

On 25 October 1510 Isabella d’Este, the Marchioness of Mantua, wrote a letter to her agent in Venice inquiring after a certain highly collectable item. ‘We believe that in the effects and the estate of Zorzo da Castelfranco, the painter, there exists a painting of a night scene, very beautiful and unusual.’

She thus set off one of the great whodunnits of art history: a mystery hidden inside an enigma that caused a furious 20th-century quarrel between one of the greatest connoisseurs of Renaissance art and the most powerful dealer of the age — and which has never been definitively solved.

It concerns a beautiful picture, now in the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, and the artist who may or may not have painted it: Giorgione of Castelfranco — just George, ‘Zorzo’, to Isabella — who had died recently of the plague.

more here.

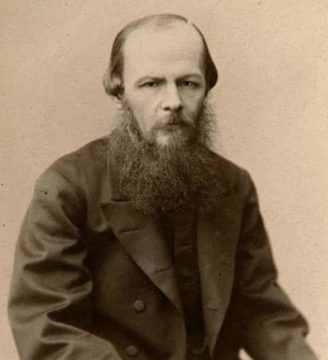

The Sinner and the Saint – a dazzling literary detective story

Alex Christofi in The Guardian:

Dostoevsky, it must be said, was no saint. He was famously cantankerous; he had at least one affair during his unhappy first marriage; he was also ruinously addicted to roulette. But he had a brilliant mind, at ease with contradiction, and was determined to use literature to pursue the moral consequences of the ideas that defined his era. To do so, Dostoevsky took inspiration from the real life story of Pierre-François Lacenaire, a charismatic gentleman murderer whose trial had been the talk of Parisian society in the 1830s, fashioning the bones of his life into one of literature’s most compelling sinners: Raskolnikov, the protagonist of Crime and Punishment, a handsome, clever and often kind university student who nonetheless murders two defenceless old women with an axe.

Dostoevsky, it must be said, was no saint. He was famously cantankerous; he had at least one affair during his unhappy first marriage; he was also ruinously addicted to roulette. But he had a brilliant mind, at ease with contradiction, and was determined to use literature to pursue the moral consequences of the ideas that defined his era. To do so, Dostoevsky took inspiration from the real life story of Pierre-François Lacenaire, a charismatic gentleman murderer whose trial had been the talk of Parisian society in the 1830s, fashioning the bones of his life into one of literature’s most compelling sinners: Raskolnikov, the protagonist of Crime and Punishment, a handsome, clever and often kind university student who nonetheless murders two defenceless old women with an axe.

The novel set Russian society ablaze on publication, with reviewers recognising it as a work of “unrivalled importance” written “with a truthfulness that shakes the soul”. (It was also prophetic: in late January 1866, just when the first chapters were being readied for publication, a law student named Danilov committed an almost identical crime.) But Crime and Punishment was no ordinary whodunnit. Instead, the book has been called a “whydunnit”, since the reader witnesses Raskolnikov’s crime in vivid detail almost immediately after the novel is under way. Throughout the story, there is a fatalistic sense that Raskolnikov cannot resist his guilt; if he is not caught, he will confess. The real question is: why? Even the murderer sometimes seems at a loss to explain his actions, and we sense that the final answer will expose the moral workings of his whole generation, who have fallen into the trap of utilitarianism, determined to found peaceful utopias by violent means.

More here.

This legendary 92-year-old biologist has some advice for saving Earth

Benji Jones in Vox:

E.O. Wilson died on December 26, according to his biodiversity foundation. The following interview was conducted with him on November 18. In the spring of 1955, E.O. Wilson, then a young entomologist at Harvard, traveled to northeastern Papua New Guinea to study ants. Hiking with local guides through dense rainforests, he climbed 13,000 feet to the summit ridge in the Saruwaged mountains — becoming, by his account, the first Western scientist to reach the peak. So much of what Wilson saw during that expedition was new to Western science, including a number of types of ants, he told Vox in a recent interview. “There were a lot of adventures like that,” said Wilson.

E.O. Wilson died on December 26, according to his biodiversity foundation. The following interview was conducted with him on November 18. In the spring of 1955, E.O. Wilson, then a young entomologist at Harvard, traveled to northeastern Papua New Guinea to study ants. Hiking with local guides through dense rainforests, he climbed 13,000 feet to the summit ridge in the Saruwaged mountains — becoming, by his account, the first Western scientist to reach the peak. So much of what Wilson saw during that expedition was new to Western science, including a number of types of ants, he told Vox in a recent interview. “There were a lot of adventures like that,” said Wilson.

Today, it may seem as though scientists have explored nearly every corner of the Earth, from the thick, humid jungles of Central Africa to the rust-red, arid outback of Australia. Walking into an ecosystem and stumbling upon species that have yet to be cataloged in academic journals now seems like something you can only read about in books that people like E.O. Wilson have written. (He’s written more than 30, and if you don’t have time to read them all, you can check out a new biography by Richard Rhodes out about him entitled Scientist: E.O. Wilson: A Life in Nature.) But that’s not how Wilson, a research professor emeritus at Harvard, sees it. In fact, much of the world’s biodiversity remains undiscovered, he told Vox. “A rough estimate suggests that there are upwards of 10 million species on the planet, and we know only a small fraction of them,” said Wilson, who popularized the term “biodiversity” in the 1980s. “The opportunities are endless.”

Sure, you might have to travel farther or study smaller organisms to find something new, he said, but there remains so much potential for discovery. And those discoveries are useful, he added, especially as we seek to conserve nature. While we already know plenty about the forces that harm ecosystems and wildlife, from habitat loss to oil spills, there’s tremendous value in knowing what we have to lose, in better understanding the planet that supports us.

I spoke with Wilson about scientific discovery for a recent episode of Vox Conversations (you can find a link below). We also chatted about how studying ants helped him understand human behavior and led to a big new conservation initiative called the Half-Earth Project. Inspired by Wilson’s book Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life, which he published in 2016, the initiative seeks to protect 50 percent of all land and ocean on the planet. The project backbone is a large dataset that shows where new protected areas would be most useful to protect biodiversity.

More here.

Cryptids “Shouldn’t” Exist, But They “Do” Anyway

Tara Isabella Burton at The Hedgehog Review:

Like its Enlightenment-era forebears, contemporary cryptozoology is rooted in that same hunger for strangeness, and for an enchanted world. It’s telling that the contemporary iteration of the phenomenon saw its first major resurgence during the wider postwar optimism of 1950s—when Belgian zoologist Bernard Heuvelmans, often lauded as one of the forefathers of the field, published On the Track of Unknown Animals in 1955. (Heuvelmans also coined the terms cryptozoology and cryptid.) Featuring entries dedicated to the abominable snowman and Nandi bears alongside examinations of platypuses and gorillas, Heuvelmans’s book celebrates the potential of a world teeming with creatures the scientific record has not yet ossified into fact.

Like its Enlightenment-era forebears, contemporary cryptozoology is rooted in that same hunger for strangeness, and for an enchanted world. It’s telling that the contemporary iteration of the phenomenon saw its first major resurgence during the wider postwar optimism of 1950s—when Belgian zoologist Bernard Heuvelmans, often lauded as one of the forefathers of the field, published On the Track of Unknown Animals in 1955. (Heuvelmans also coined the terms cryptozoology and cryptid.) Featuring entries dedicated to the abominable snowman and Nandi bears alongside examinations of platypuses and gorillas, Heuvelmans’s book celebrates the potential of a world teeming with creatures the scientific record has not yet ossified into fact.

“The world is by no means thoroughly explored,” Heuvelmans writes in his introduction. “It is true that we know almost all its geography, there are no more large islands or continents to be discovered.

more here.

Wednesday Poem

The Return

He doesn’t know it yet, but when my father

and I return there, it will be forever.

His antihypertensives thrown away,

his briefcase in the attic left to waste,

the football game turned off— he’s snoring now,

he doesn’t even dream it, but I know

I’ll carry him the way he carried me

when I was small: In 2023

my father’s shrunken, eighty-five years old,

weighs ninety pounds, a little dazed but thrilled

that Castro’s long been dead, his son impeached!

He doesn’t know it, dozing on the couch

across the family room from me, but this

is what I’ve dreamed of giving him, just this.

And as I carry him upon my shoulders,

triumphant strides across a beach so golden

I want to cry, that’s when he sees for sure,

he sees he’s needed me for all these years.

He doesn’t understand it yet, but when

I give him Cuba, he will love me then.

by Rafael Campo

from El Coro

University of Massachusetts Press, 1997

Tara Isabella Burton + Ross Douthat: Strange Rites

Tuesday, December 28, 2021

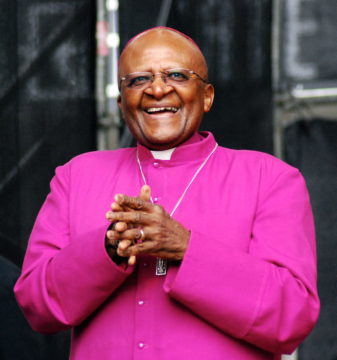

Desmond Tutu Opposed Capitalism, Israeli Apartheid and US/UK Imperialism, Too

David Rovics in Counterpunch:

This may sound either arrogant or forgetful, but I could not possibly remember the number of times I was in the same room or at the same protest as Desmond Tutu. And the main reason I know he was there is because I was there listening to him speak, often from a distance of not more than two meters or so. I say this not to associate myself with the great man — though I’ll forgive you for thinking I’m a terrible, narcissistic name-dropper — but just to be sure we all know this all really happened, because I saw and heard it.

This may sound either arrogant or forgetful, but I could not possibly remember the number of times I was in the same room or at the same protest as Desmond Tutu. And the main reason I know he was there is because I was there listening to him speak, often from a distance of not more than two meters or so. I say this not to associate myself with the great man — though I’ll forgive you for thinking I’m a terrible, narcissistic name-dropper — but just to be sure we all know this all really happened, because I saw and heard it.

It seems very important to mention, because of the way this man is already being remembered by the world’s pundits and politicians. As anyone could have predicted, Tutu is being remembered as the great opponent of apartheid in his native South Africa, who was one of the most recognized and most eloquent leaders of the anti-apartheid struggle there, for most of his adult life.

Being a leader in the movement to end apartheid in South Africa was probably the greatest achievement of the man’s life work, and it should come as a surprise to no one that this is the focus of his many obituaries, along with the Nobel he was awarded in 1984. After Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, he was remembered by the establishment in much the same way, as a leader of the movement against apartheid in the US. The fact that he had become one of the most well-known and well-loved voices of the antiwar movement in the United States and around the world at the time of his death has largely been written out of the history books, a very inconvenient truth.

But as with Martin Luther King, many of the same political leaders commemorating Tutu today would have been unlikely to mention him a day earlier, lest Tutu take the opportunity to speak his mind. This is certainly why he was not invited to commemorate his friend and comrade, Nelson Mandela, at Mandela’s funeral eight years ago.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen: Part II

….. “I saw Jesus in the Projects.”

…………………….. —Richard Pryor

Every street corner is Christmas Eve

in downtown Newark. The Magi walk

in black overcoats hugging a fifth

of methylated spirits, and hookers hook

nothing from the dark cribs of doorways.

A crazy king breaks a bottle in praise

of Welfare, ‘I’ll kill the motherfucker,’

and for black blocks without work

the sky is full of crystal splinters.

A bus breaks out of the mirage of water,

a hippo in wet streetlights, and grinds on

in smoke; every shadow seems to stagger

under the fiery acids of neon –

wavering like a piss, some l tt rs miss-

ing, extinguished – except for two white

nurses, their vocation made whiter

in darkness. It’s two days from elections.

Johannesburg is full of starlit shebeens.

It is anti-American to make such connections.

Think of Newark as Christmas Eve,

when all men are your brothers, even

these; bring peace to us in parcels,

let there be no more broken bottles in heaven

over Newark, let it not shine like spit

on a doorstep, think of the evergreen

apex with the gold star over it

on the Day-Glo bumper sticker a passing car sells.

Daughter of your own Son, Mother and Virgin,

great is the sparkle of the high-rise firmament

in acid puddles, the gold star in store windows,

and the yellow star on the night’s moth-eaten sleeve

like the black coat He wore through blade-thin elbows

out of the ghetto into the cattle train

from Warsaw; nowhere is His coming more immanent

than downtown Newark, where three lights believe

the starlit cradle, and the evergreen carols

to the sparrow-child: a black coat-flapping urchin

followed by a white star as a police car patrols.

by Derek Walcott

from Arkansas Testament

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, NY, 1987

“The Christmas Story” by Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Nabokov in the New York Review of Books:

Silence fell. Pitilessly illuminated by the lamplight, young and plump-faced, wearing a side-buttoned Russian blouse under his black jacket, his eyes tensely downcast, Anton Golïy began gathering the manuscript pages that he had discarded helter-skelter during his reading. His mentor, the critic from Red Reality, stared at the floor as he patted his pockets in search of some matches. The writer Novodvortsev was silent too, but his was a different, venerable, silence. Wearing a substantial pince-nez, exceptionally large of forehead, two strands of his sparse dark hair pulled across his bald pate, gray streaks on his close-cropped temples, he sat with closed eyes as if he were still listening, his heavy legs crossed and one hand compressed between a kneecap and a hamstring. This was not the first time he had been subjected to such glum, earnest rustic fictionists. And not the first time he had detected, in their immature narratives, echoes—not yet noted by the critics—of his own twenty-five years of writing; for Golïy’s story was a clumsy rehash of one of his subjects, that of The Verge, a novella he had excitedly and hopefully composed, whose publication the previous year had done nothing to enhance his secure but pallid reputation.

Silence fell. Pitilessly illuminated by the lamplight, young and plump-faced, wearing a side-buttoned Russian blouse under his black jacket, his eyes tensely downcast, Anton Golïy began gathering the manuscript pages that he had discarded helter-skelter during his reading. His mentor, the critic from Red Reality, stared at the floor as he patted his pockets in search of some matches. The writer Novodvortsev was silent too, but his was a different, venerable, silence. Wearing a substantial pince-nez, exceptionally large of forehead, two strands of his sparse dark hair pulled across his bald pate, gray streaks on his close-cropped temples, he sat with closed eyes as if he were still listening, his heavy legs crossed and one hand compressed between a kneecap and a hamstring. This was not the first time he had been subjected to such glum, earnest rustic fictionists. And not the first time he had detected, in their immature narratives, echoes—not yet noted by the critics—of his own twenty-five years of writing; for Golïy’s story was a clumsy rehash of one of his subjects, that of The Verge, a novella he had excitedly and hopefully composed, whose publication the previous year had done nothing to enhance his secure but pallid reputation.

More here.

One woman’s six-word mantra that has helped to calm millions

Judith Hoare in Psyche:

Imagine being in a pandemic, isolated and inert. Your life feels out of control, and you are stressed, not sleeping well. Then a raft of bewildering new symptoms arrive – perhaps your heart races unexpectedly, or you feel lightheaded. Maybe your stomach churns and parts of your body seem to have an alarming life of their own, all insisting something is badly wrong. You are less afraid of the pandemic than of the person you have now become.

Imagine being in a pandemic, isolated and inert. Your life feels out of control, and you are stressed, not sleeping well. Then a raft of bewildering new symptoms arrive – perhaps your heart races unexpectedly, or you feel lightheaded. Maybe your stomach churns and parts of your body seem to have an alarming life of their own, all insisting something is badly wrong. You are less afraid of the pandemic than of the person you have now become.

Most terrifying of all is the invasive flashes of fear in the absence of any specific threat.

Back in 1927, this was 24-year-old Claire Weekes. A brilliant young scholar on her way to becoming the first woman to attain a doctorate of science at the University of Sydney,

More here.

Breaking Down the Mostly Real Science Behind “Don’t Look Up”

Jeffrey Kluger in Time:

Want a good, solid, rollicking laugh? Contemplate the end of the world—the whole existential shebang: the annihilation of civilization, the extinction of all species, the death of the entire Earthly biomass. Funny, right? Actually, yes—and arch and ironic and dark and smart, at least in the hands of Adam McKay (The Big Short, Vice), whose new film Don’t Look Up was released in theaters on Dec. 10 and is set to begin streaming on Netflix Dec. 24.

Want a good, solid, rollicking laugh? Contemplate the end of the world—the whole existential shebang: the annihilation of civilization, the extinction of all species, the death of the entire Earthly biomass. Funny, right? Actually, yes—and arch and ironic and dark and smart, at least in the hands of Adam McKay (The Big Short, Vice), whose new film Don’t Look Up was released in theaters on Dec. 10 and is set to begin streaming on Netflix Dec. 24.

The premise of the film is equal parts broad, plausible and utterly terrifying. A comet measuring up to 9 km (5.6 mi.) across is discovered by Ph.D candidate Kate Dibiasky (Jennifer Lawrence), while she is conducting routine telescopic surveys searching for supernovae. Kudos and back-slaps from her colleagues follow—find a comet, after all, and you get to give it your name. But the good times stop when her adviser, Dr. Randall Mindy ((Leonardo DiCaprio), crunches the trajectory numbers and determines that Comet Dibiasky—which is about the same size as the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago—is on course to collide with Earth in a planet-killing crack-up exactly six months and 14 days later.

More here.