Carl Zimmer in The New York Times:

When Dr. Wilson began his career in evolutionary biology in the 1950s, the study of animals and plants seemed to many scientists like a quaint, obsolete hobby. Molecular biologists were getting their first glimpses of DNA, proteins and other invisible foundations of life. Dr. Wilson made it his life’s work to put evolution on an equal footing. “How could our seemingly old-fashioned subjects achieve new intellectual rigor and originality compared to molecular biology?” he recalled in 2009. He answered his own question by pioneering new fields of research. As an expert on insects, Dr. Wilson studied the evolution of behavior, exploring how natural selection and other forces could produce something as extraordinarily complex as an ant colony. He then championed this kind of research as a way of making sense of all behavior — including our own. As part of his campaign, Dr. Wilson wrote a string of books that influenced his fellow scientists while also gaining a broad public audience. “On Human Nature” won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction in 1979; “The Ants,” which Dr. Wilson wrote with his longtime colleague Bert Hölldobler, won him his second Pulitzer, in 1991.

When Dr. Wilson began his career in evolutionary biology in the 1950s, the study of animals and plants seemed to many scientists like a quaint, obsolete hobby. Molecular biologists were getting their first glimpses of DNA, proteins and other invisible foundations of life. Dr. Wilson made it his life’s work to put evolution on an equal footing. “How could our seemingly old-fashioned subjects achieve new intellectual rigor and originality compared to molecular biology?” he recalled in 2009. He answered his own question by pioneering new fields of research. As an expert on insects, Dr. Wilson studied the evolution of behavior, exploring how natural selection and other forces could produce something as extraordinarily complex as an ant colony. He then championed this kind of research as a way of making sense of all behavior — including our own. As part of his campaign, Dr. Wilson wrote a string of books that influenced his fellow scientists while also gaining a broad public audience. “On Human Nature” won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction in 1979; “The Ants,” which Dr. Wilson wrote with his longtime colleague Bert Hölldobler, won him his second Pulitzer, in 1991.

Dr. Wilson also became a pioneer in the study of biological diversity, developing a mathematical approach to questions about why different places have different numbers of species. Later in his career, he became one of the world’s leading voices for the protection of endangered wildlife.

Dr. Wilson, a professor for 46 years at Harvard, was famous for his shy demeanor and gentle Southern charm, but they hid a fierce determination. By his own admission, he was “roused by the amphetamine of ambition.” His ambitions earned him many critics as well. Some condemned what they considered simplistic accounts of human nature. Other evolutionary biologists attacked him for reversing his views on natural selection late in his career.

More here.

On the afternoon of Christmas Day 1956, in a snow-covered field on the outskirts of the small Swiss town of Herisau, some children and their dog discovered the body of a dead man, hand clutched tight to his stilled heart. It was the writer Robert Walser, who had died that day, aged seventy-eight, while out walking far from the mental institution where he had dwelled for the previous two decades. A photograph taken by the local medical examiner Kurt Giezendanner shows the body at rest, left arm thrown out as in the style of a sleeper midway through a restless night, while two shadowy figures at the margins look on. The sorrow of the scene is rather gently assuaged by the odd fact that Walser’s hat, perhaps moved by a breeze, lies at a modest distance from his body, as if it has leapt off his head to cartoonishly express surprise at its owner’s death. A few distant trees squeeze into the top of the frame like awkward mourners paying their respects. The snow, even on the ground but for a few shaggy lumps close to his boots, appears at first to be nothing more than a dazzling absence, as if the dead Walser were floating on a white winter sky.

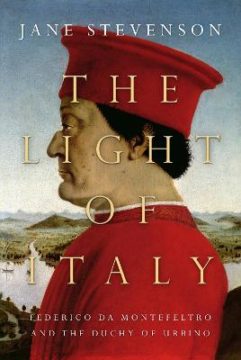

On the afternoon of Christmas Day 1956, in a snow-covered field on the outskirts of the small Swiss town of Herisau, some children and their dog discovered the body of a dead man, hand clutched tight to his stilled heart. It was the writer Robert Walser, who had died that day, aged seventy-eight, while out walking far from the mental institution where he had dwelled for the previous two decades. A photograph taken by the local medical examiner Kurt Giezendanner shows the body at rest, left arm thrown out as in the style of a sleeper midway through a restless night, while two shadowy figures at the margins look on. The sorrow of the scene is rather gently assuaged by the odd fact that Walser’s hat, perhaps moved by a breeze, lies at a modest distance from his body, as if it has leapt off his head to cartoonishly express surprise at its owner’s death. A few distant trees squeeze into the top of the frame like awkward mourners paying their respects. The snow, even on the ground but for a few shaggy lumps close to his boots, appears at first to be nothing more than a dazzling absence, as if the dead Walser were floating on a white winter sky. Federico is a figure well worthy of attention. Born on the wrongish side of the blanket in 1420s (it was a crowded part of the bed at that time in Italy), he became ruler of Urbino in his early twenties after the assassination of his unpopular half-brother. While there is no evidence that he was involved in the plot, he was hovering conveniently nearby when it happened. The citizens who approached him to take over presented him with a list of unnegotiable demands, the most stringent of which was to abolish a set of recently introduced taxes and promise not to impose new ones. In itself, this was an impressive demand in a country filled with minor despots. Even more impressively, Federico kept his word.

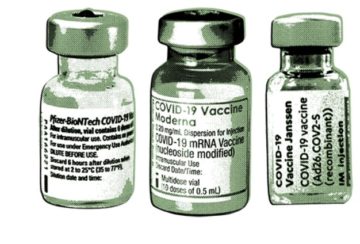

Federico is a figure well worthy of attention. Born on the wrongish side of the blanket in 1420s (it was a crowded part of the bed at that time in Italy), he became ruler of Urbino in his early twenties after the assassination of his unpopular half-brother. While there is no evidence that he was involved in the plot, he was hovering conveniently nearby when it happened. The citizens who approached him to take over presented him with a list of unnegotiable demands, the most stringent of which was to abolish a set of recently introduced taxes and promise not to impose new ones. In itself, this was an impressive demand in a country filled with minor despots. Even more impressively, Federico kept his word. This year, mercifully, saw quite a few notable improvements

This year, mercifully, saw quite a few notable improvements  Matthew Mehan

Matthew Mehan Cities are bastions of opportunity. They are filled with vast numbers of people meeting friends and family, visiting restaurants, museums, concert halls and sporting events, and travelling to and from jobs. Yet many of us who live in cities have occasionally been overwhelmed by the activity. At other times, we might feel ‘alone in the crowd’. For decades, the conflicting experiences of city living have led urbanites and scholars to ask: are cities bad for mental health?

Cities are bastions of opportunity. They are filled with vast numbers of people meeting friends and family, visiting restaurants, museums, concert halls and sporting events, and travelling to and from jobs. Yet many of us who live in cities have occasionally been overwhelmed by the activity. At other times, we might feel ‘alone in the crowd’. For decades, the conflicting experiences of city living have led urbanites and scholars to ask: are cities bad for mental health? NASA just got a $10 billion space telescope for Christmas.

NASA just got a $10 billion space telescope for Christmas.

If there’s one thing we’ve learned

If there’s one thing we’ve learned  Joe Bucciero in The Nation:

Joe Bucciero in The Nation: Lisa Herzog in The Raven:

Lisa Herzog in The Raven: Massimo Pigliucci in Aeon:

Massimo Pigliucci in Aeon: In 2019, the year Keegan Fong opened

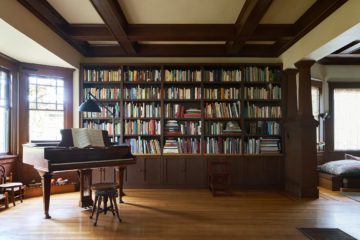

In 2019, the year Keegan Fong opened  At the turn of the millennium, Reid Byers, a computer systems architect, set out to build a private library at his home in Princeton, N.J. Finding few books on library architecture that were not centuries old and in a dead or mildewed language, he took the advice of a neighbor across the street, the novelist Toni Morrison. Ms. Morrison “once famously said if there is a book you want to read and it doesn’t exist, then you must write it,” recalled Mr. Byers, 74, in a video chat from his current home, in Portland, Maine. The project stretched over a generation and culminated this year in a profusely illustrated, detail-crammed, Latin-strewn and yet remarkably unstuffy book called “

At the turn of the millennium, Reid Byers, a computer systems architect, set out to build a private library at his home in Princeton, N.J. Finding few books on library architecture that were not centuries old and in a dead or mildewed language, he took the advice of a neighbor across the street, the novelist Toni Morrison. Ms. Morrison “once famously said if there is a book you want to read and it doesn’t exist, then you must write it,” recalled Mr. Byers, 74, in a video chat from his current home, in Portland, Maine. The project stretched over a generation and culminated this year in a profusely illustrated, detail-crammed, Latin-strewn and yet remarkably unstuffy book called “ Joan Didion is not a nice person. I would almost put her in the category of Michel Houellebecq and Witold Gombrowicz. But not quite. I’m not sure what quality it is that holds her just at the cusp of “evil writer” without her falling in. Perhaps it is that she believes, though she would never put it this way, in the redemptive capacity of the act of writing.

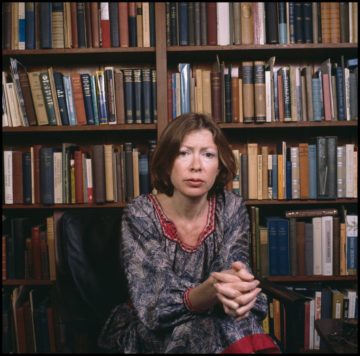

Joan Didion is not a nice person. I would almost put her in the category of Michel Houellebecq and Witold Gombrowicz. But not quite. I’m not sure what quality it is that holds her just at the cusp of “evil writer” without her falling in. Perhaps it is that she believes, though she would never put it this way, in the redemptive capacity of the act of writing. Joan Didion was 5 years old when she wrote her first story, upon the instruction of her mother, who had told her to stop whining and to write down her thoughts. She amused herself by describing a woman who imagines she is about to freeze to death, only to die burning instead.

Joan Didion was 5 years old when she wrote her first story, upon the instruction of her mother, who had told her to stop whining and to write down her thoughts. She amused herself by describing a woman who imagines she is about to freeze to death, only to die burning instead.