Alun Salt in Botany One:

There’s more recognition that ecological restoration can be an essential tool in fighting climate change, and there are many projects aimed at restoring degraded forests to capture carbon. Still, the focus on forests ignores much of the land in the tropics that would not naturally be forested. A team of scientists is arguing that people need to become aware of other habitats and their value.

There’s more recognition that ecological restoration can be an essential tool in fighting climate change, and there are many projects aimed at restoring degraded forests to capture carbon. Still, the focus on forests ignores much of the land in the tropics that would not naturally be forested. A team of scientists is arguing that people need to become aware of other habitats and their value.

There’s increased understanding that not only do we need to cut carbon dioxide emissions, we also need to pull it from the atmosphere. Recently trees have come into fashion as the answer. This need has led to the Trillion Tree Campaign and a company in the UK planting giant redwoods to offset a lifetime’s carbon on the basis that “planting native trees to combat climate change is a little like bringing a water pistol to a gun fight.” Ecologists working outside forests could feel a little neglected. Research recently published in the Journal of Applied Ecology by Fernando A. O. Silveira and colleagues showed that they’d be right. And it’s not just the public that is fixating on trees. The study shows that scientists and policymakers are focussing disproportionately on trees too. This problem, which they label Biome Awareness Disparity or BAD, could have consequences for conservation in the future.

More here.

The pandemic has unveiled the reality behind what’s been vexing the academic humanities for decades. Classes went online, as business demanded. Classes returned to in-person, as business demanded. Since humanities enrollments have been declining, naturally higher education has been hiring more administrators to hire consultants to figure out how to attract what we’ve grown used to calling its customer base—or, if that doesn’t pan out, to provide a rationale for cutting its programs. When students and administrators aren’t teaming up against professors for not delivering what the customer wants, all parties seem to have made a non-aggression pact for reasons that have almost nothing to do with liberal education.

The pandemic has unveiled the reality behind what’s been vexing the academic humanities for decades. Classes went online, as business demanded. Classes returned to in-person, as business demanded. Since humanities enrollments have been declining, naturally higher education has been hiring more administrators to hire consultants to figure out how to attract what we’ve grown used to calling its customer base—or, if that doesn’t pan out, to provide a rationale for cutting its programs. When students and administrators aren’t teaming up against professors for not delivering what the customer wants, all parties seem to have made a non-aggression pact for reasons that have almost nothing to do with liberal education. Feynman: There was a sister. There was a brother that came after approximately three years. Or maybe I was five, four, six, three, I don’t remember. But that brother died, after a relatively short time, like a month or so. I can still remember that, so I can’t have been too young, because I can remember especially that the brother had a finger bleeding all the time. That’s what happened — it was some kind of disease that didn’t heal. And also, asking the nurse how they knew whether it was a boy or a girl, and being taught: it’s by the shape of the ear — and thinking that that’s rather strange. There’s so much difference in the world between men and women that they should bother to make any difference, a boy from a girl, with just the shape of the ear! It didn’t sound like a sensible thing. Now, I remember that I had another, a sister, when I was nine years old, so it’s possible that I’m remembering my question at the age of nine or ten, and not at the age of the other child, because it sounds incredible to me now that I would have had such a deep thought about society at the earlier age. I don’t know. I can’t tell you what age I was, but I remember that, because it was an interesting answer. I couldn’t understand it really. They make such a fuss — everybody dresses differently; they go to so much trouble, their hair different — just because the ear shape is different? What sort of an answer is that?

Feynman: There was a sister. There was a brother that came after approximately three years. Or maybe I was five, four, six, three, I don’t remember. But that brother died, after a relatively short time, like a month or so. I can still remember that, so I can’t have been too young, because I can remember especially that the brother had a finger bleeding all the time. That’s what happened — it was some kind of disease that didn’t heal. And also, asking the nurse how they knew whether it was a boy or a girl, and being taught: it’s by the shape of the ear — and thinking that that’s rather strange. There’s so much difference in the world between men and women that they should bother to make any difference, a boy from a girl, with just the shape of the ear! It didn’t sound like a sensible thing. Now, I remember that I had another, a sister, when I was nine years old, so it’s possible that I’m remembering my question at the age of nine or ten, and not at the age of the other child, because it sounds incredible to me now that I would have had such a deep thought about society at the earlier age. I don’t know. I can’t tell you what age I was, but I remember that, because it was an interesting answer. I couldn’t understand it really. They make such a fuss — everybody dresses differently; they go to so much trouble, their hair different — just because the ear shape is different? What sort of an answer is that? Many people have told me that they cannot cook to save their lives. I don’t believe them. A lot of them can build a dresser out of an IKEA box – despite the fact that the instructions read like they were written by a wall-eyed robot whose first language was Esperanto, while writing code in C++ or programming a television set to switch between the news and a soccer match. How could it be possible that they are not able to follow a simple set of instructions?

Many people have told me that they cannot cook to save their lives. I don’t believe them. A lot of them can build a dresser out of an IKEA box – despite the fact that the instructions read like they were written by a wall-eyed robot whose first language was Esperanto, while writing code in C++ or programming a television set to switch between the news and a soccer match. How could it be possible that they are not able to follow a simple set of instructions? Before she married her husband, Kiersten Little considered him ideal father material. “We were always under the mentality of, ‘Oh yeah, when you get married, you have kids,” she said. “It was this expected thing.” Expected, that is, until the couple took an eight-month road trip after Ms. Little got her master’s degree in public health at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, N.C. “When we were out west — California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho — we were driving through areas where the whole forest was dead, trees knocked over,” Ms. Little said. “We went through southern Louisiana, which was hit by two hurricanes last year, and whole towns were leveled, with massive trees pulled up by their roots.” Now 30 and two years into her marriage, Ms. Little feels “the burden of knowledge,” she said. The couple sees mounting disaster when reading the latest

Before she married her husband, Kiersten Little considered him ideal father material. “We were always under the mentality of, ‘Oh yeah, when you get married, you have kids,” she said. “It was this expected thing.” Expected, that is, until the couple took an eight-month road trip after Ms. Little got her master’s degree in public health at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, N.C. “When we were out west — California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho — we were driving through areas where the whole forest was dead, trees knocked over,” Ms. Little said. “We went through southern Louisiana, which was hit by two hurricanes last year, and whole towns were leveled, with massive trees pulled up by their roots.” Now 30 and two years into her marriage, Ms. Little feels “the burden of knowledge,” she said. The couple sees mounting disaster when reading the latest  Like many of the great perfumers, Jean Carles was a son of Grasse, a country town in the hills north of Cannes, on the French Riviera. Grasse, once a state unto itself, sits in a natural amphitheater of south-facing limestone cliffs, at the head of a valley of meadows sloping gently to the sea. The combined effect of this geography and the dulcet Mediterranean climate is a harvest of roses, jasmine, and bitter-orange blossoms that is exceptionally fragrant, and for hundreds of years the town has been known as the capital of the perfume trade. When Carles began his training, early in the twentieth century, a priesthood of Grassois perfumers presided over the industry. These so-called nez, or noses, were regarded with an awe of the sort that attaches, perhaps especially in France, to artistic genius. They were vessels of divine talent, their creations as wondrously perfect as the flowers of Grasse.

Like many of the great perfumers, Jean Carles was a son of Grasse, a country town in the hills north of Cannes, on the French Riviera. Grasse, once a state unto itself, sits in a natural amphitheater of south-facing limestone cliffs, at the head of a valley of meadows sloping gently to the sea. The combined effect of this geography and the dulcet Mediterranean climate is a harvest of roses, jasmine, and bitter-orange blossoms that is exceptionally fragrant, and for hundreds of years the town has been known as the capital of the perfume trade. When Carles began his training, early in the twentieth century, a priesthood of Grassois perfumers presided over the industry. These so-called nez, or noses, were regarded with an awe of the sort that attaches, perhaps especially in France, to artistic genius. They were vessels of divine talent, their creations as wondrously perfect as the flowers of Grasse. P

P “There was a period when he was turning out 7,000 words a day,” writes Tomalin. “He kept working at what seems an impossible rate, producing stories so varied one might easily think they came from a team of writers.” Few writers will equal his worldwide impact on letters. With Jules Verne and the publisher Hugo Gernsback, he invented the genre of science fiction. A crater on the moon’s far side is named after him. Nominated four times for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Wells, the futurist, foresaw the coming of aircraft, tanks, the sexual revolution, the atomic bomb, and created the classic templates for every story that has been written about alien invasion (his inspiration for “The War of the Worlds,” says Tomalin, was “Tasmania, and the disaster the arrival of the Europeans had been for its people, who were annihilated”) and time travel (he was the first to imagine such travel made possible by a machine).

“There was a period when he was turning out 7,000 words a day,” writes Tomalin. “He kept working at what seems an impossible rate, producing stories so varied one might easily think they came from a team of writers.” Few writers will equal his worldwide impact on letters. With Jules Verne and the publisher Hugo Gernsback, he invented the genre of science fiction. A crater on the moon’s far side is named after him. Nominated four times for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Wells, the futurist, foresaw the coming of aircraft, tanks, the sexual revolution, the atomic bomb, and created the classic templates for every story that has been written about alien invasion (his inspiration for “The War of the Worlds,” says Tomalin, was “Tasmania, and the disaster the arrival of the Europeans had been for its people, who were annihilated”) and time travel (he was the first to imagine such travel made possible by a machine). Willem deVries in Aeon:

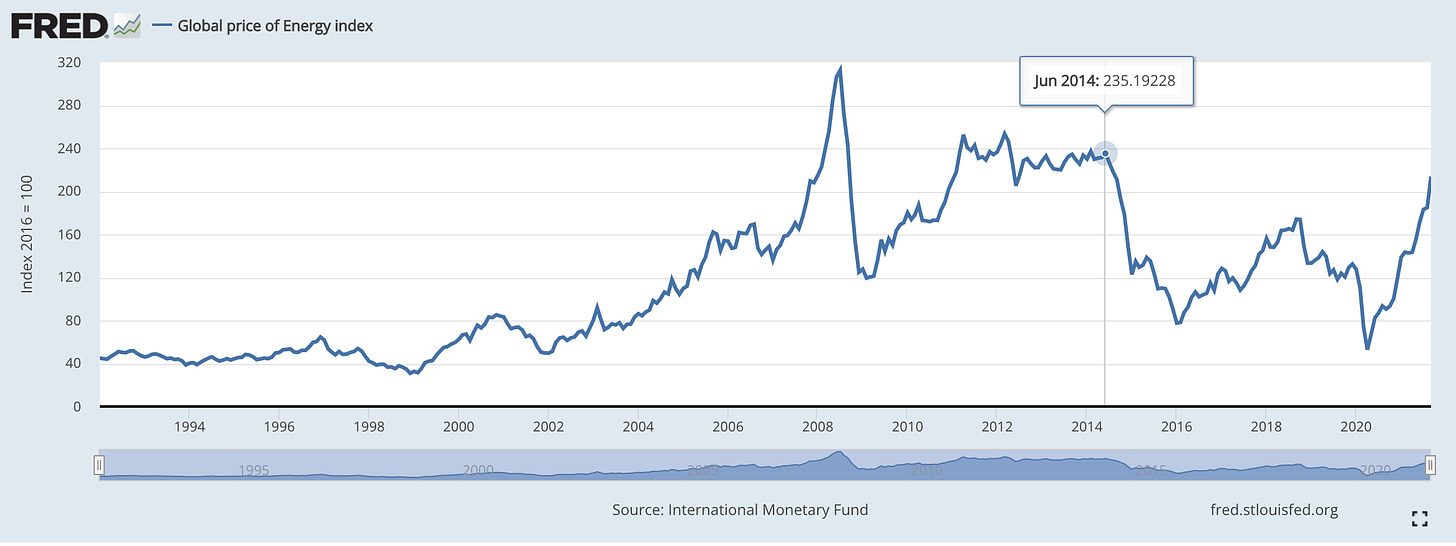

Willem deVries in Aeon: Cedric Durand and Adam Tooze debate if and how the current shortfall in energy supply is directly connected to climate policy. First,

Cedric Durand and Adam Tooze debate if and how the current shortfall in energy supply is directly connected to climate policy. First,