Emily Stewart in Vox:

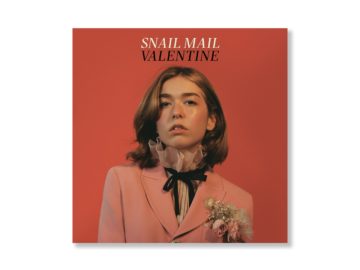

The supply chain comes for everyone, including Adele. Or maybe it’s Adele who’s coming for the supply chain — specifically, the vinyl supply chain.

The supply chain comes for everyone, including Adele. Or maybe it’s Adele who’s coming for the supply chain — specifically, the vinyl supply chain.

The British songstress released her latest album, 30, on Friday to much global fanfare, and she’s expected to do major worldwide sales (at a moment when physical music sales are rare). There’s been speculation that Adele’s big splash may also have implications for the music business, and not necessarily all good ones. Sony Music reportedly ordered some 500,000 copies of vinyl records for the album’s release, potentially putting a squeeze on an already tight supply chain. With Adele pressing all those records, there has been speculation that she’s crowding out some space for others. At the very least, the issue is drawing some attention to a real crunch in the music industry. “All of these bigger artists are selling more records on vinyl, and all of them together are clogging up the plants, whereas a few years ago, vinyl was probably second-tier for these artists or even third-tier,” said Mike Quinn, head of sales at ATO Records, an independent record label based in New York City. But he’s not worried too much. “We’ve not had any plant turn us down saying, ‘Oh, we have too many Adele records.’”

Vinyl has seen a renaissance over the past decade or so, with demand surging even more during the pandemic. According to the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), vinyl sales grew by 28.7 percent in value from 2019 to 2020 to $626 million. Last year also marked the first year vinyl exceeded CDs in total revenue since the 1980s. Manufacturers have struggled to keep up. “Vinyl’s been surging, or resurging, from the dark ages since probably 2007, 2008. It just did so under the radar,” said Brandon Seavers, co-founder and CEO of Memphis Records, a vinyl manufacturer. “The pandemic hit, and everything exploded.” Adele isn’t at fault for the vinyl supply chain’s problems. She, like all artists, wants to sell a lot of records, and even without her, the industry has been facing delays and setbacks and struggling to keep up with skyrocketing demand for quite some time. As Shamir, one Philadelphia musician, put it in an interview with NPR, “Adele is not the culprit” but also “is not helping.”

More here.

What an innocent I am. Until I read Isobel Williams’s reinventions of Catullus as Shibari Carmina I would have guessed that ‘shibari’ was an exotic seasoning, or perhaps a rare type of plant. Having now looked it up online and averted my gaze from the pictures (what ads will I get served in future? Will my IT department shop me?), I learn it’s a form of Japanese bondage, which involves consenting adults and carefully calibrated widths and strengths of jute rope. I’m sure the jute makes all the difference, and that nylon would be quite horrid. Or maybe just more horrid. The person doing the tying up in shibari is regarded as the servant of the person being trussed, and the loops of jute are defined in a series of elegant moves as though the whole thing were a martial art, so the activity inverts expectations about power relations even while seeming to make them pretty darn obvious.

What an innocent I am. Until I read Isobel Williams’s reinventions of Catullus as Shibari Carmina I would have guessed that ‘shibari’ was an exotic seasoning, or perhaps a rare type of plant. Having now looked it up online and averted my gaze from the pictures (what ads will I get served in future? Will my IT department shop me?), I learn it’s a form of Japanese bondage, which involves consenting adults and carefully calibrated widths and strengths of jute rope. I’m sure the jute makes all the difference, and that nylon would be quite horrid. Or maybe just more horrid. The person doing the tying up in shibari is regarded as the servant of the person being trussed, and the loops of jute are defined in a series of elegant moves as though the whole thing were a martial art, so the activity inverts expectations about power relations even while seeming to make them pretty darn obvious.

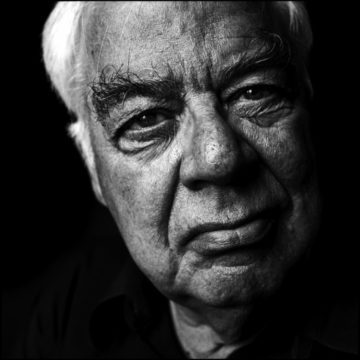

Stephen Sondheim, one of Broadway history’s songwriting titans, whose music and lyrics raised and reset the artistic standard for the American stage musical, died early Friday at his home in Roxbury, Conn. He was 91. His lawyer and friend, F. Richard Pappas, announced the death. He said he did not know the cause but added that Mr. Sondheim had not been known to be ill and that the death was sudden. The day before, Mr. Sondheim had celebrated Thanksgiving with a dinner with friends in Roxbury, Mr. Pappas said.

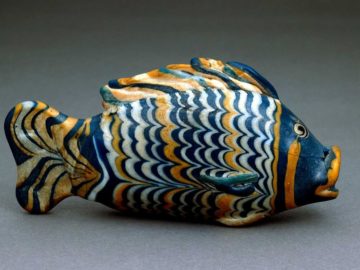

Stephen Sondheim, one of Broadway history’s songwriting titans, whose music and lyrics raised and reset the artistic standard for the American stage musical, died early Friday at his home in Roxbury, Conn. He was 91. His lawyer and friend, F. Richard Pappas, announced the death. He said he did not know the cause but added that Mr. Sondheim had not been known to be ill and that the death was sudden. The day before, Mr. Sondheim had celebrated Thanksgiving with a dinner with friends in Roxbury, Mr. Pappas said. Today, glass is ordinary, on-the-kitchen-shelf stuff. But early in its history, glass was bling for kings. Thousands of years ago, the pharaohs of ancient Egypt surrounded themselves with the stuff, even in death, leaving stunning specimens for archaeologists to uncover. King Tutankhamen’s tomb housed a

Today, glass is ordinary, on-the-kitchen-shelf stuff. But early in its history, glass was bling for kings. Thousands of years ago, the pharaohs of ancient Egypt surrounded themselves with the stuff, even in death, leaving stunning specimens for archaeologists to uncover. King Tutankhamen’s tomb housed a

Fraud in biomedical research, though relatively uncommon, damages the scientific community by diminishing the integrity of the ecosystem and sending other scientists down fruitless paths. When exposed and publicized, fraud also reduces public respect for the research enterprise, which is required for its success. Although the human frailties that contribute to fraud are as old as our species, the response of the research community to allegations of fraud has dramatically changed. This is well illustrated by three prominent cases known to the author over 40 years. In the first, I participated as auditor in an ad hoc process that, lacking institutional definition and oversight, was open to abuse, though it eventually produced an appropriate result. In the second, I was a faculty colleague of a key participant whose case helped shape guidelines for management of future cases. The third transpired during my time overseeing the well-developed if sometimes overly bureaucratized investigatory process for research misconduct at Harvard Medical School, designed in accordance with prevailing regulations. These cases illustrate many of the factors contributing to fraudulent biomedical research in the modern era and the changing institutional responses to it, which should further evolve to be more efficient and transparent.

Fraud in biomedical research, though relatively uncommon, damages the scientific community by diminishing the integrity of the ecosystem and sending other scientists down fruitless paths. When exposed and publicized, fraud also reduces public respect for the research enterprise, which is required for its success. Although the human frailties that contribute to fraud are as old as our species, the response of the research community to allegations of fraud has dramatically changed. This is well illustrated by three prominent cases known to the author over 40 years. In the first, I participated as auditor in an ad hoc process that, lacking institutional definition and oversight, was open to abuse, though it eventually produced an appropriate result. In the second, I was a faculty colleague of a key participant whose case helped shape guidelines for management of future cases. The third transpired during my time overseeing the well-developed if sometimes overly bureaucratized investigatory process for research misconduct at Harvard Medical School, designed in accordance with prevailing regulations. These cases illustrate many of the factors contributing to fraudulent biomedical research in the modern era and the changing institutional responses to it, which should further evolve to be more efficient and transparent. In March 2020, Boris Johnson, pale and exhausted, self-isolating in his flat on Downing Street, released a video of himself – that he had taken himself – reassuring Britons that they would get through the pandemic, together. “One thing I think the coronavirus crisis has already proved is that there really is such a thing as society,” the prime minister

In March 2020, Boris Johnson, pale and exhausted, self-isolating in his flat on Downing Street, released a video of himself – that he had taken himself – reassuring Britons that they would get through the pandemic, together. “One thing I think the coronavirus crisis has already proved is that there really is such a thing as society,” the prime minister  I thought often about something the saxophonist Pharoah Sanders said, after

I thought often about something the saxophonist Pharoah Sanders said, after  Why have I come so far on a literary pilgrimage? I want to be unafraid to move in the world again. But what do I expect from a visit to the three-quarters-Canadian, one-quarter-American poet Elizabeth Bishop’s childhood home? “Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?” Bishop asks in her marvelous poem “Questions of Travel.” Am I, like her, dreaming my dream and having it too? Is it a lack of imagination that brings me to Great Village? “Shouldn’t you have stayed at home and thought of here?” I can hear her asking. I wish my friend Rachel were here as planned. She would know the answers to these questions. She is receiving a new treatment and isn’t herself. In 1979, on the weekend that Bishop died, Rachel knocked on her door at 437 Lewis Wharf—Rachel still lives upstairs—because she knew Bishop wasn’t feeling well, and offered to bring her some milk and eggs from the local market, but Bishop demurred. A couple of days later, Bishop’s friend and companion Alice Methfessel phoned to say that Elizabeth had died and that she didn’t want Rachel to be shocked to read about it in the newspaper.

Why have I come so far on a literary pilgrimage? I want to be unafraid to move in the world again. But what do I expect from a visit to the three-quarters-Canadian, one-quarter-American poet Elizabeth Bishop’s childhood home? “Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?” Bishop asks in her marvelous poem “Questions of Travel.” Am I, like her, dreaming my dream and having it too? Is it a lack of imagination that brings me to Great Village? “Shouldn’t you have stayed at home and thought of here?” I can hear her asking. I wish my friend Rachel were here as planned. She would know the answers to these questions. She is receiving a new treatment and isn’t herself. In 1979, on the weekend that Bishop died, Rachel knocked on her door at 437 Lewis Wharf—Rachel still lives upstairs—because she knew Bishop wasn’t feeling well, and offered to bring her some milk and eggs from the local market, but Bishop demurred. A couple of days later, Bishop’s friend and companion Alice Methfessel phoned to say that Elizabeth had died and that she didn’t want Rachel to be shocked to read about it in the newspaper. Richard Rorty (1931–2007) was the philosopher’s anti-philosopher. His professional credentials were impeccable: an influential anthology (The Linguistic Turn, 1967); a game-changing book (Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, 1979); another, only slightly less original book (Consequences of Pragmatism, 1982); a best-selling (for a philosopher) collection of literary/philosophical/political lectures and essays (Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, 1989); four volumes of Collected Papers from the venerable Cambridge University Press; president of the Eastern Division of the American Philosophical Association (1979). He seemed to be speaking at every humanities conference in the 1980s and 1990s, about postmodernism, critical theory, deconstruction, and the past, present, and future (if any) of philosophy.

Richard Rorty (1931–2007) was the philosopher’s anti-philosopher. His professional credentials were impeccable: an influential anthology (The Linguistic Turn, 1967); a game-changing book (Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, 1979); another, only slightly less original book (Consequences of Pragmatism, 1982); a best-selling (for a philosopher) collection of literary/philosophical/political lectures and essays (Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, 1989); four volumes of Collected Papers from the venerable Cambridge University Press; president of the Eastern Division of the American Philosophical Association (1979). He seemed to be speaking at every humanities conference in the 1980s and 1990s, about postmodernism, critical theory, deconstruction, and the past, present, and future (if any) of philosophy. Tiny is pregnant, but not as we know it: she is expecting an “owl-baby”, the result of a secret tryst with a female “owl-lover”. “This baby will never learn to speak, or love, or look after itself”, Tiny knows. Her husband, an intellectual property lawyer, thinks her panic is just pregnancy jitters, and that she’s carrying his child. Even when he finds a disembowelled possum on the path and his “well fed” wife sitting in the dark (“It didn’t feel dark to me. I see everything”), he doesn’t believe. Then the baby is born.

Tiny is pregnant, but not as we know it: she is expecting an “owl-baby”, the result of a secret tryst with a female “owl-lover”. “This baby will never learn to speak, or love, or look after itself”, Tiny knows. Her husband, an intellectual property lawyer, thinks her panic is just pregnancy jitters, and that she’s carrying his child. Even when he finds a disembowelled possum on the path and his “well fed” wife sitting in the dark (“It didn’t feel dark to me. I see everything”), he doesn’t believe. Then the baby is born. In her preface to the 2021 paperback edition of Thanksgiving, marking the 400th anniversary of the American Thanksgiving, Melanie Kirkpatrick expresses her concern for the continued celebration of the venerable holiday. “Given recent attacks on Washington, Lincoln, and other heroes of American history, it was only a matter of time before cancel culture came for Thanksgiving.” (x) Her use of the word “heroes” clearly places her on a particular side in this installment of the culture wars, but her worry is legitimate. Thanksgiving could fall, condemned as a symbol, a relic of White supremacy, simultaneously celebrating and masking genocide, colonialism, and racism, just as Columbus Day has died an ignoble (and for many a deserved) death across a good swath of the United States. The fact that Kirkpatrick does not touch upon this at all in the introduction to the 2016 edition of her book shows just how decisive (Kirkpatrick would probably say destructive) a force cancel culture has become in a mere five years.

In her preface to the 2021 paperback edition of Thanksgiving, marking the 400th anniversary of the American Thanksgiving, Melanie Kirkpatrick expresses her concern for the continued celebration of the venerable holiday. “Given recent attacks on Washington, Lincoln, and other heroes of American history, it was only a matter of time before cancel culture came for Thanksgiving.” (x) Her use of the word “heroes” clearly places her on a particular side in this installment of the culture wars, but her worry is legitimate. Thanksgiving could fall, condemned as a symbol, a relic of White supremacy, simultaneously celebrating and masking genocide, colonialism, and racism, just as Columbus Day has died an ignoble (and for many a deserved) death across a good swath of the United States. The fact that Kirkpatrick does not touch upon this at all in the introduction to the 2016 edition of her book shows just how decisive (Kirkpatrick would probably say destructive) a force cancel culture has become in a mere five years. Today the reduction procedure, known as the Laporta algorithm, has become the main tool for generating precise predictions about particle behavior. “It’s ubiquitous,” said

Today the reduction procedure, known as the Laporta algorithm, has become the main tool for generating precise predictions about particle behavior. “It’s ubiquitous,” said  The United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP26) fell far short of what is needed for a safe planet, owing mainly to the same lack of trust that has burdened global climate negotiations for almost three decades. Developing countries regard climate change as a crisis caused largely by the rich countries, which they also view as shirking their historical and ongoing responsibility for the crisis. Worried that they will be left paying the bills, many key developing countries, such as India, don’t much care to negotiate or strategize.

The United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP26) fell far short of what is needed for a safe planet, owing mainly to the same lack of trust that has burdened global climate negotiations for almost three decades. Developing countries regard climate change as a crisis caused largely by the rich countries, which they also view as shirking their historical and ongoing responsibility for the crisis. Worried that they will be left paying the bills, many key developing countries, such as India, don’t much care to negotiate or strategize. My last pandemic Thanksgiving dinner began in a jet black convertible-turned-restaurant booth where I watched as a teenaged pizzamaker took a break from scattering toppings on my 18-inch Supreme pie to take a hit and turn up “Heartbreakin’ Man” by My Morning Jacket. Spinelli’s Pizzeria in Louisville’s Highland neighborhood possesses a kind of curated grime. It’s covered in graffiti-style art (which is unsurprising because its staff is often a rotation of local taggers) and is packed with muscle car and pop culture ephemera, including a

My last pandemic Thanksgiving dinner began in a jet black convertible-turned-restaurant booth where I watched as a teenaged pizzamaker took a break from scattering toppings on my 18-inch Supreme pie to take a hit and turn up “Heartbreakin’ Man” by My Morning Jacket. Spinelli’s Pizzeria in Louisville’s Highland neighborhood possesses a kind of curated grime. It’s covered in graffiti-style art (which is unsurprising because its staff is often a rotation of local taggers) and is packed with muscle car and pop culture ephemera, including a  The

The