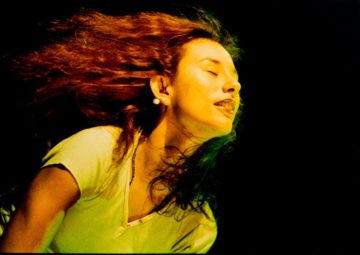

Claire Chambers in Dawn:

I’ve been reading Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb’s ambitious debut monograph, Epidemic Empire: Colonialism, Contagion and Terror 1817–2020. In it, the Pakistani-American scholar ranges over 200 years of history to argue that the West has long used the language of disease centrally in its methods of control.

I’ve been reading Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb’s ambitious debut monograph, Epidemic Empire: Colonialism, Contagion and Terror 1817–2020. In it, the Pakistani-American scholar ranges over 200 years of history to argue that the West has long used the language of disease centrally in its methods of control.

What inspires Kolb’s thesis is Susan Sontag’s argument from Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors about a pervasive and dangerous entanglement of war imagery and medical diction. According to the renowned American critic, similes and metaphors, signs and signifiers act as misleading bridges between wars and pandemics.

Kolb extends Sontag’s ideas to talk about the way in which terror and insurgency are widely positioned as a “viruslike” epidemic. Such imagery of contagion has, she submits, been the defining trope of Islamophobic discourse among imperialists from the 1857 Indian Rebellion onwards.

More here.

Her continued experimentation on paper notwithstanding, beginning in the late 1960s, Thomas seems to have concentrated on all-over paintings constructed with regular, rhythmic patches of color chained into vertical bands, concentric circles, or o

Her continued experimentation on paper notwithstanding, beginning in the late 1960s, Thomas seems to have concentrated on all-over paintings constructed with regular, rhythmic patches of color chained into vertical bands, concentric circles, or o “There’s always the lingering thought, left in the air, of whether this is goodbye,” said Christopher Hitchens as we sat in his Washington apartment one bright winter’s afternoon. And for us, I knew that it was. There was no question about it. Christopher had advanced cancer of the oesophagus—a peculiarly cruel fate for one known for, literally and metaphorically, his voice. “In whatever kind of a ‘race’ life may be,” he had written in Vanity Fair in 2010, “I have very abruptly become a finalist.” He departed life on 15th December 2011, aged 62, with much still left to say.

“There’s always the lingering thought, left in the air, of whether this is goodbye,” said Christopher Hitchens as we sat in his Washington apartment one bright winter’s afternoon. And for us, I knew that it was. There was no question about it. Christopher had advanced cancer of the oesophagus—a peculiarly cruel fate for one known for, literally and metaphorically, his voice. “In whatever kind of a ‘race’ life may be,” he had written in Vanity Fair in 2010, “I have very abruptly become a finalist.” He departed life on 15th December 2011, aged 62, with much still left to say. In 2012, the singer and songwriter John Mellencamp was given the John Steinbeck Award, presented annually to an artist, thinker, activist, or writer whose work exemplifies, among other virtues, Steinbeck’s “belief in the dignity of people who by circumstance are pushed to the fringes.” The grace of the marginalized is a long-standing theme of Mellencamp’s writing. The musician, who comes from Indiana and began releasing records in the late nineteen-seventies, is known as a populist soothsayer, an irascible and unpretentious spokesman for hardworking, rural-born folks. Yet Mellencamp has also bristled at this characterization, which is largely rooted in fantasy: men gazing wistfully out the windows of vintage pickup trucks, watching dust blow by, listening to some parched and distant radio station. The image of such “real,” non-coastal Americans has become a useful cudgel for conservatives looking to depict their opponents as élitist buffoons; Mellencamp finds this grotesque. “Let’s address the ‘voice of the heartland’ thing,” he told Paul Rees, whose satisfying biography, “Mellencamp,” came out last year. “Indiana is a red state. And you’re looking at the most liberal motherfucker you know. I am for the total overthrow of the capitalist system. Let’s get all those motherfuckers out of here.”

In 2012, the singer and songwriter John Mellencamp was given the John Steinbeck Award, presented annually to an artist, thinker, activist, or writer whose work exemplifies, among other virtues, Steinbeck’s “belief in the dignity of people who by circumstance are pushed to the fringes.” The grace of the marginalized is a long-standing theme of Mellencamp’s writing. The musician, who comes from Indiana and began releasing records in the late nineteen-seventies, is known as a populist soothsayer, an irascible and unpretentious spokesman for hardworking, rural-born folks. Yet Mellencamp has also bristled at this characterization, which is largely rooted in fantasy: men gazing wistfully out the windows of vintage pickup trucks, watching dust blow by, listening to some parched and distant radio station. The image of such “real,” non-coastal Americans has become a useful cudgel for conservatives looking to depict their opponents as élitist buffoons; Mellencamp finds this grotesque. “Let’s address the ‘voice of the heartland’ thing,” he told Paul Rees, whose satisfying biography, “Mellencamp,” came out last year. “Indiana is a red state. And you’re looking at the most liberal motherfucker you know. I am for the total overthrow of the capitalist system. Let’s get all those motherfuckers out of here.” It may seem hard to believe, but each one of us began as a single cell that proliferated into the trillions of cells that make up our bodies. Though each of our cells has the exact same genetic information, each also performs a specialized function: neurons govern our thoughts and behaviors, for example, while immune cells learn to recognize and fight off disease, skin cells protect us from the outside world, muscle cells enable movement, and so on.

It may seem hard to believe, but each one of us began as a single cell that proliferated into the trillions of cells that make up our bodies. Though each of our cells has the exact same genetic information, each also performs a specialized function: neurons govern our thoughts and behaviors, for example, while immune cells learn to recognize and fight off disease, skin cells protect us from the outside world, muscle cells enable movement, and so on. David Hume (1711–1776) is justly considered to be one of the greatest philosophers that Western civilization has produced. His legacy, however, is a strange one: The works for which he was most celebrated in his lifetime are now largely ignored, while those that had the smallest impact have fared better over time.

David Hume (1711–1776) is justly considered to be one of the greatest philosophers that Western civilization has produced. His legacy, however, is a strange one: The works for which he was most celebrated in his lifetime are now largely ignored, while those that had the smallest impact have fared better over time. Wind and solar power vary over the course of a day, so energy storage is essential to provide a continuous flow of electricity. But today’s batteries are typically quite small and store enough energy for only a few hours of electricity. To rely more on wind and solar power, the U.S. will need more overnight and longer-term storage as well.

Wind and solar power vary over the course of a day, so energy storage is essential to provide a continuous flow of electricity. But today’s batteries are typically quite small and store enough energy for only a few hours of electricity. To rely more on wind and solar power, the U.S. will need more overnight and longer-term storage as well. Years of litigation and reporting leave no doubt about Guantánamo’s function. The plans for the prison were formulated in the months following Congress’s 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force, which became law a week after the September 11 attacks and remains in effect today. In December that year, Department of Justice lawyers John Yoo and Patrick Philbin sent a

Years of litigation and reporting leave no doubt about Guantánamo’s function. The plans for the prison were formulated in the months following Congress’s 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force, which became law a week after the September 11 attacks and remains in effect today. In December that year, Department of Justice lawyers John Yoo and Patrick Philbin sent a  If you were to trace both “sides” of a Möbius strip, you would never have to lift your finger. A single-sided surface with no boundaries, the strip is an artist’s reverie and a mathematician’s feat. A typical thought experiment to demonstrate how the three-dimensional strip operates involves imagining an ant on an adventure. Picture the insect traversing the Möbius band. One apparent loop would land the ant not where it started but upside down, only halfway through a full circuit. After two loops, the ant would be back at the beginning—but dizzy.

If you were to trace both “sides” of a Möbius strip, you would never have to lift your finger. A single-sided surface with no boundaries, the strip is an artist’s reverie and a mathematician’s feat. A typical thought experiment to demonstrate how the three-dimensional strip operates involves imagining an ant on an adventure. Picture the insect traversing the Möbius band. One apparent loop would land the ant not where it started but upside down, only halfway through a full circuit. After two loops, the ant would be back at the beginning—but dizzy. Psychoanalysis might be the science of the soul, but it has never been the science of the disembodied soul. Freud was a medical researcher and clinician, and arrived at his method by attending to the bodies in the consulting room. He knew that voice and hearing were bodily affordances, and that technological aids and prostheses were part of daily life, not to be sneered at. In his 1913 essay “On Beginning the Treatment,” Freud describes how he arrived at his most important technological signature, the couch. Tired of his patients staring at him all day, he decided to have them recline, facing away from him. But he also noted that the arrangement in which a patient lies on a couch while the analyst sits behind them, out of sight, “has a historical basis; it is the remnant of the hypnotic method out of which psycho-analysis was evolved.” Freud went on: “I insist on this procedure . . . to isolate the transference and to allow it to come forward in due course sharply defined as a resistance.”

Psychoanalysis might be the science of the soul, but it has never been the science of the disembodied soul. Freud was a medical researcher and clinician, and arrived at his method by attending to the bodies in the consulting room. He knew that voice and hearing were bodily affordances, and that technological aids and prostheses were part of daily life, not to be sneered at. In his 1913 essay “On Beginning the Treatment,” Freud describes how he arrived at his most important technological signature, the couch. Tired of his patients staring at him all day, he decided to have them recline, facing away from him. But he also noted that the arrangement in which a patient lies on a couch while the analyst sits behind them, out of sight, “has a historical basis; it is the remnant of the hypnotic method out of which psycho-analysis was evolved.” Freud went on: “I insist on this procedure . . . to isolate the transference and to allow it to come forward in due course sharply defined as a resistance.” Lynch’s adoration of musicians has been a constant, and he’s often blurred the line between musical and on-screen performance. In Blue Velvet (a film named after a 1950 ballad), Frank Booth is almost driven mad by the beauty of Roy Orbison’s 1963 song “In Dreams,” as lip-synced by Dean Stockwell’s character. Composer Angelo Badalamenti has played an outsized emotional role in every Lynch project since Blue Velvet, where he also appears in-world as Dorothy’s pianist. Lynch loved “Mysteries of Love” singer Julee Cruise so much that, after making an entire album with her, he planted her among the residents of Twin Peaks as a performer at the Roadhouse. Twin Peaks’ James Hurley (James Marshall) is a would-be Chris Isaak, a sentimental singer with a guitar, a motorcycle, and a heart of gold. Lynch also frequently uses musicians as actors, as he did with Sting in Dune, Henry Rollins in Lost Highway, Chrysta Bell in Twin Peaks: The Return—and David Bowie, who appears alongside Isaak in Fire Walk with Me. “Musicians are very close to actors,” Lynch told me, simply. “They go in front of people on a stage, and they have really no problem being in public, just like being in front of a camera. And they perform.”

Lynch’s adoration of musicians has been a constant, and he’s often blurred the line between musical and on-screen performance. In Blue Velvet (a film named after a 1950 ballad), Frank Booth is almost driven mad by the beauty of Roy Orbison’s 1963 song “In Dreams,” as lip-synced by Dean Stockwell’s character. Composer Angelo Badalamenti has played an outsized emotional role in every Lynch project since Blue Velvet, where he also appears in-world as Dorothy’s pianist. Lynch loved “Mysteries of Love” singer Julee Cruise so much that, after making an entire album with her, he planted her among the residents of Twin Peaks as a performer at the Roadhouse. Twin Peaks’ James Hurley (James Marshall) is a would-be Chris Isaak, a sentimental singer with a guitar, a motorcycle, and a heart of gold. Lynch also frequently uses musicians as actors, as he did with Sting in Dune, Henry Rollins in Lost Highway, Chrysta Bell in Twin Peaks: The Return—and David Bowie, who appears alongside Isaak in Fire Walk with Me. “Musicians are very close to actors,” Lynch told me, simply. “They go in front of people on a stage, and they have really no problem being in public, just like being in front of a camera. And they perform.” Notwithstanding their sometimes tendentious selection of evidence, conservative critics are right about one thing: progressives do like to tell people what to call things. The well-rehearsed rhetorical drama over this kind of conceptual terminology is only one of the ways in which arguments over definitions and usage have risen to prominence and in some cases become almost synonymous with the desire for social change in recent years. On one hand, progressives push to substitute centuries-old terms with wide public currency like “hunger” and “homelessness” with recondite neologisms like “food insecurity” and “unhoused persons.” At the same time, they insist that familiar—if familiarly contested—terms like “racism,” “white supremacy” and “violence” be expanded to cover huge new swaths of attitudes, institutional arrangements and beliefs, including many (such as “freedom of speech,” or the prospect of a “color-blind” society) that the majority of Americans still think of as signaling positively virtuous commitments. That many of these efforts meet with mockery, resistance and recrimination only seems to reinforce confidence on all sides that the battle is a crucial one.

Notwithstanding their sometimes tendentious selection of evidence, conservative critics are right about one thing: progressives do like to tell people what to call things. The well-rehearsed rhetorical drama over this kind of conceptual terminology is only one of the ways in which arguments over definitions and usage have risen to prominence and in some cases become almost synonymous with the desire for social change in recent years. On one hand, progressives push to substitute centuries-old terms with wide public currency like “hunger” and “homelessness” with recondite neologisms like “food insecurity” and “unhoused persons.” At the same time, they insist that familiar—if familiarly contested—terms like “racism,” “white supremacy” and “violence” be expanded to cover huge new swaths of attitudes, institutional arrangements and beliefs, including many (such as “freedom of speech,” or the prospect of a “color-blind” society) that the majority of Americans still think of as signaling positively virtuous commitments. That many of these efforts meet with mockery, resistance and recrimination only seems to reinforce confidence on all sides that the battle is a crucial one. At the centre of her debut album, Little Earthquakes, released 30 years ago, is “Me and a Gun”, an a cappella song about a rape so brutal that were Amos emerging now, the experience would define her entire public identity. In a few of her earliest interviews, her rape is edited out, passed over as “a frightful event”, though she had clearly spent part of the interview talking about it. Who knows whether it scared the male-dominated music press of the 1990s; whether it contributed to the way Tori Amos was seen – as someone both away with the fairies and too raw and physical to be comfortable with. An NME review of Little Earthquakes described it as “a sprawling, confusing journey through the gunk of a woman’s soul”. Her brand of sexuality was a challenge for straight men, as she humped her piano, or suckled a pig in images for her third album, Boys For Pele. She was no Kate Bush after all. Asked once who would play her in a film, she replied: Tonya Harding.

At the centre of her debut album, Little Earthquakes, released 30 years ago, is “Me and a Gun”, an a cappella song about a rape so brutal that were Amos emerging now, the experience would define her entire public identity. In a few of her earliest interviews, her rape is edited out, passed over as “a frightful event”, though she had clearly spent part of the interview talking about it. Who knows whether it scared the male-dominated music press of the 1990s; whether it contributed to the way Tori Amos was seen – as someone both away with the fairies and too raw and physical to be comfortable with. An NME review of Little Earthquakes described it as “a sprawling, confusing journey through the gunk of a woman’s soul”. Her brand of sexuality was a challenge for straight men, as she humped her piano, or suckled a pig in images for her third album, Boys For Pele. She was no Kate Bush after all. Asked once who would play her in a film, she replied: Tonya Harding.