Atlantic City, June 23, 1957 (AP) — President Eisenhower’s pastor said tonight that Americans are living in a period of “unprecedented religious activity” caused partially by paid vacations, the eight-hour day, and modern conveniences.

“These fruits of material progress,” said the Reverend … of the National Presbyterian Church, Washington, “have provided the leisure, the energy, and the means for a level of human and spiritual values never before reached.”

… Sees boom in religion to.

Boom

Here at the Vespasian-Carlton, it’s just one

religious activity after another; the sky

is constantly being crossed by cruciform

airplanes, in which nobody disbelieves

for a second, and the tide, the tide

of spiritual progress and prosperity

miraculously keeps rising to a level

never before obtained. The churches are full,

the beaches are full, God’s great ocean is full

of paid vacationers praying an eight-hour day

to the human and spiritual values, the fruits,

the leisure, the energy, and the means, Lord,

the means for the level, the unprecedented level,

and the modern conveniences, which also are full.

Never before, O Lord, have the prayers and praises

from belfry, from phonebooth, from ballpark and barbecue

and sacrifices, so endlessly ascended.

It was not thus when Job in Palestine

sat in the dust and cried, cried bitterly;

when Damien kissed the lepers on their wounds

it was not thus; it was not thus

when Francis worked a fourteen-hour day

strictly for the birds; when Dante took

a week’s vacation without pay when it rained

part of the time, O Lord, it was not thus.

But now the gears mesh and the tires burn

and the ice chatters in the shaker and the priest

in the pulpit, and Thy Name, O Lord,

is kept before the public, while the fruits

ripen and religion booms and the level rises

and every modern convenience runneth over,

that it may never be with us as it hath been

with Athens and Karnak and Nagasaki,

nor Thy sun for one instant refrain from shining

on the rainbow Buick by the breezeway

or the Chris Craft with the uplift life raft;

that we may continue to be the just folk we are,

plain people with ordinary superliners, people of the stop’n’shop

‘n’ pray as you go, of hotel, motel, boatel,

the humble pilgrims of no deposit no return

and please adjust thy clothing, who will give to Thee,

if Thee will keep us going, our annual

Miss Universe, for Thy Name’s Sake, Amen.

by Howard Nemerov

from The American Experience: Poetry

Macmillen Company, 1968

It is hard to imagine humans spending their lives in virtual reality when the experience amounts to waving your arms about in the middle of the lounge with a device the size of a house brick strapped to your face.

It is hard to imagine humans spending their lives in virtual reality when the experience amounts to waving your arms about in the middle of the lounge with a device the size of a house brick strapped to your face. Gravity might be an early subject in introductory physics classes, but that doesn’t mean scientists aren’t still trying to measure it with ever-increasing precision. Now, a group of physicists has done it using the effects of

Gravity might be an early subject in introductory physics classes, but that doesn’t mean scientists aren’t still trying to measure it with ever-increasing precision. Now, a group of physicists has done it using the effects of  If debt ensures stability and solvency for some, the economic growth it propels fuels dependency and inequality for others, not only between creditor and debtor but also further down the line, as the borrower passes on the costs of debt to those with less power to control the terms of the deal. This devil’s bargain is particularly true when it comes to municipal debt, argues the Stanford University historian Destin Jenkins in The Bonds of Inequality, his new book on the power the bond market has leveraged over San Francisco and other US cities. The debt-financed spending that cities have long used to spur growth, Jenkins contends, has also underwritten the racial and income inequality of the post–World War II metropolis, while funneling profits to bankers and reinforcing city dependency on finance capitalism.

If debt ensures stability and solvency for some, the economic growth it propels fuels dependency and inequality for others, not only between creditor and debtor but also further down the line, as the borrower passes on the costs of debt to those with less power to control the terms of the deal. This devil’s bargain is particularly true when it comes to municipal debt, argues the Stanford University historian Destin Jenkins in The Bonds of Inequality, his new book on the power the bond market has leveraged over San Francisco and other US cities. The debt-financed spending that cities have long used to spur growth, Jenkins contends, has also underwritten the racial and income inequality of the post–World War II metropolis, while funneling profits to bankers and reinforcing city dependency on finance capitalism. In the late 19th century, a Sunday school leader in New York, Charles C. Overton, called for the

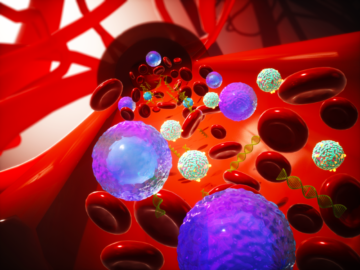

In the late 19th century, a Sunday school leader in New York, Charles C. Overton, called for the  A connection between the human herpesvirus Epstein-Barr and multiple sclerosis (MS) has long been suspected but has been difficult to prove. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is the primary cause of mononucleosis and is so common that 95 percent of adults carry it. Unlike Epstein-Barr, MS, a devastating demyelinating disease of the central nervous system, is relatively rare. It affects 2.8 million people worldwide. But people who contract infectious mononucleosis are at slightly increased risk of developing MS. In the disease, inflammation damages the myelin sheath that insulates nerve cells, ultimately disrupting signals to and from the brain and causing a variety of symptoms, from numbness and pain to paralysis.

A connection between the human herpesvirus Epstein-Barr and multiple sclerosis (MS) has long been suspected but has been difficult to prove. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is the primary cause of mononucleosis and is so common that 95 percent of adults carry it. Unlike Epstein-Barr, MS, a devastating demyelinating disease of the central nervous system, is relatively rare. It affects 2.8 million people worldwide. But people who contract infectious mononucleosis are at slightly increased risk of developing MS. In the disease, inflammation damages the myelin sheath that insulates nerve cells, ultimately disrupting signals to and from the brain and causing a variety of symptoms, from numbness and pain to paralysis. Nobody wants to hear anyone else’s dreams, and nobody wants to see anyone else’s photo albums. A rare few good souls might express interest at first, but will almost certainly find their attention flagging long before the sharer is finished.

Nobody wants to hear anyone else’s dreams, and nobody wants to see anyone else’s photo albums. A rare few good souls might express interest at first, but will almost certainly find their attention flagging long before the sharer is finished. After the Omicron wave, we’ll be in a world where most people will have some sort of immunity, either through natural infections, vaccines, or both. We now know how to get vaccines fast (we should approve them faster for new variants), and we have treatments too. The value of time for learning has dropped: we know most of what we need to know about it. So the benefits of social measures to stop COVID are much lower.

After the Omicron wave, we’ll be in a world where most people will have some sort of immunity, either through natural infections, vaccines, or both. We now know how to get vaccines fast (we should approve them faster for new variants), and we have treatments too. The value of time for learning has dropped: we know most of what we need to know about it. So the benefits of social measures to stop COVID are much lower.

I

I With apologies to Tolstoy, all perfect rhymes are alike, each imperfect rhyme imperfect in its own way. Perfect rhyme tells us about a relationship between words that never changes; that scoring with boring is a rhyme you can find in a dictionary is useful but also, not to put too fine a point on it, boring. But rhyming family with body—that’s interesting. How does she do it? Why does she do it? Imperfect rhyme—slant rhyme, off-rhyme, near-rhyme, half-rhyme, lazy rhyme, deferred rhyme, overzealous compound rhyme, corrugated rhyme, what have you—illuminates something about the person creating it, about their ear and their mind and what they’re willing to bend for the sake of sound. It tells us what they believe they can get away with through sheer force of will, like how Fabolous rhymes Beamer Benz or Bentley with team be spending centuries and penis evidently just because he knows he can.

With apologies to Tolstoy, all perfect rhymes are alike, each imperfect rhyme imperfect in its own way. Perfect rhyme tells us about a relationship between words that never changes; that scoring with boring is a rhyme you can find in a dictionary is useful but also, not to put too fine a point on it, boring. But rhyming family with body—that’s interesting. How does she do it? Why does she do it? Imperfect rhyme—slant rhyme, off-rhyme, near-rhyme, half-rhyme, lazy rhyme, deferred rhyme, overzealous compound rhyme, corrugated rhyme, what have you—illuminates something about the person creating it, about their ear and their mind and what they’re willing to bend for the sake of sound. It tells us what they believe they can get away with through sheer force of will, like how Fabolous rhymes Beamer Benz or Bentley with team be spending centuries and penis evidently just because he knows he can. Israel is often seen as a place of intractable divisions. But author Ethan Michaeli, the son of Israelis who moved to the United States, grew weary of hearing the same old narratives. So he set out on a journey to paint a more nuanced portrait. In “Twelve Tribes: Promise and Peril in the New Israel,” he brings readers along for the ride, introducing them to the complexities – and humanity – of life in modern Israel. A deeper understanding won’t fix everything, he says, but it may help uplift the debate. He spoke recently with the Monitor.

Israel is often seen as a place of intractable divisions. But author Ethan Michaeli, the son of Israelis who moved to the United States, grew weary of hearing the same old narratives. So he set out on a journey to paint a more nuanced portrait. In “Twelve Tribes: Promise and Peril in the New Israel,” he brings readers along for the ride, introducing them to the complexities – and humanity – of life in modern Israel. A deeper understanding won’t fix everything, he says, but it may help uplift the debate. He spoke recently with the Monitor. “We’ve known for many years that there is tumour-related material in the blood stream,” says Minetta C. Liu. “We just didn’t have the technologies to detect it with enough sensitivity for it to be meaningful.”

“We’ve known for many years that there is tumour-related material in the blood stream,” says Minetta C. Liu. “We just didn’t have the technologies to detect it with enough sensitivity for it to be meaningful.” To comfort friends discouraged by their writing pace, you could offer them this:

To comfort friends discouraged by their writing pace, you could offer them this: Human beings, unlike all the other animals, hate animal bodies, especially their own. Not all human beings, not all the time. Leopold Bloom, pleased by the taste of urine, and, later, by the smell of his own shit rising up to his nostrils in the outhouse (“He read on, pleased by his own rising smell”), is a rare and significant exception, to whom I shall return. But most people’s daily lives are dominated by arts of concealing embodiment and its signs. The first of those disguises is, of course, clothing. But also deodorant, mouthwash, nose-hair clipping, waxing, perfume, dieting, cosmetic surgery — the list goes on and on. In 1732, in his poem “The Lady’s Dressing Room,” Jonathan Swift imagines a lover who believes his beloved to be some sort of angelic sprite, above mere bodily things. Now he is allowed into her empty boudoir. There he discovers all sorts of disgusting remnants: sweaty laundry; combs containing “A paste of composition rare, Sweat, dandruff, powder, lead, and hair”; a basin containing “the scrapings of her teeth and gums”; towels soiled with dirt, sweat, and earwax; snotty handkerchiefs; stockings exuding the perfume of “stinking toes”; tweezers to remove chin-hairs; and at last underwear bearing the unmistakable marks and smells of excrement. “Disgusted Strephon stole away/Repeating in his amorous fits,/Oh! Celia, Ceila, Celia shits!”

Human beings, unlike all the other animals, hate animal bodies, especially their own. Not all human beings, not all the time. Leopold Bloom, pleased by the taste of urine, and, later, by the smell of his own shit rising up to his nostrils in the outhouse (“He read on, pleased by his own rising smell”), is a rare and significant exception, to whom I shall return. But most people’s daily lives are dominated by arts of concealing embodiment and its signs. The first of those disguises is, of course, clothing. But also deodorant, mouthwash, nose-hair clipping, waxing, perfume, dieting, cosmetic surgery — the list goes on and on. In 1732, in his poem “The Lady’s Dressing Room,” Jonathan Swift imagines a lover who believes his beloved to be some sort of angelic sprite, above mere bodily things. Now he is allowed into her empty boudoir. There he discovers all sorts of disgusting remnants: sweaty laundry; combs containing “A paste of composition rare, Sweat, dandruff, powder, lead, and hair”; a basin containing “the scrapings of her teeth and gums”; towels soiled with dirt, sweat, and earwax; snotty handkerchiefs; stockings exuding the perfume of “stinking toes”; tweezers to remove chin-hairs; and at last underwear bearing the unmistakable marks and smells of excrement. “Disgusted Strephon stole away/Repeating in his amorous fits,/Oh! Celia, Ceila, Celia shits!” Denial of Omicron being serious suits an exhausted community who just wish life could go back to 2019. Omicron may be half as deadly as Delta, but Delta was twice as deadly as the 2020 virus. Importantly, the WHO assesses the risk of Omicron as high and reiterates that adequate data on severity in unvaccinated people is not yet available. Even if hospitalisation, admissions to intensive care and death rates are half that of Delta, daily case numbers are 20-30 times higher – and projected to get to 200 times higher. A tsunami of cases will result in large hospitalisation numbers. It is already overwhelming health systems, which common colds and seasonal flu don’t. Nor do they result in ambulance wait times of hours for life-threatening conditions. In addition, a tsunami of absenteeism in the workplace will worsen current shortages, supply chain disruptions and even critical infrastructure such as power. The ACTU has called for an urgent raft of measures to address the workforce crisis.

Denial of Omicron being serious suits an exhausted community who just wish life could go back to 2019. Omicron may be half as deadly as Delta, but Delta was twice as deadly as the 2020 virus. Importantly, the WHO assesses the risk of Omicron as high and reiterates that adequate data on severity in unvaccinated people is not yet available. Even if hospitalisation, admissions to intensive care and death rates are half that of Delta, daily case numbers are 20-30 times higher – and projected to get to 200 times higher. A tsunami of cases will result in large hospitalisation numbers. It is already overwhelming health systems, which common colds and seasonal flu don’t. Nor do they result in ambulance wait times of hours for life-threatening conditions. In addition, a tsunami of absenteeism in the workplace will worsen current shortages, supply chain disruptions and even critical infrastructure such as power. The ACTU has called for an urgent raft of measures to address the workforce crisis.