Bilingual/Bilingue

My father liked them separate, one there,

one here (allá y aquí), as if aware

that words might cut in two his daughter’s heart

(el corazón) and lock the alien part

to what he was—his memory, his name

(su nombre)—with a key he could not claim.

“English outside this door, Spanish inside,”

he said, “y basta.” But who can divide

the world, the word (mundo y palabra) from

any child? I knew how to be dumb

and stubborn (testaruda); late, in bed,

I hoarded secret syllables I read

until my tongue (mi lengua) learned to run

where his stumbled. And still the heart was one.

I like to think he knew that, even when,

proud (orgulloso) of his daughter’s pen,

he stood outside mis versos, half in fear

of words he loved but wanted not to hear.

by Rhina P. Espaillat

from Poetry Out Loud

The Poetry Foundation, 2005

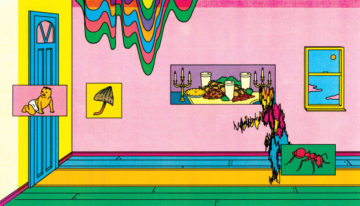

The creature appears to be, at first glance, a parrot, with bright feathers in yellow, red, green, and blue. But another look, and one sees that it’s shaped more like a duck, or perhaps two ducks melded into one. What looks like an eye might really be the wing of a butterfly. The more closely one looks at the image, the more the creature is unrecognizable; it dissolves into a strange jumble of component parts, which seem to add up to nothing, and then cohere once again into something both familiar and unknown.

The creature appears to be, at first glance, a parrot, with bright feathers in yellow, red, green, and blue. But another look, and one sees that it’s shaped more like a duck, or perhaps two ducks melded into one. What looks like an eye might really be the wing of a butterfly. The more closely one looks at the image, the more the creature is unrecognizable; it dissolves into a strange jumble of component parts, which seem to add up to nothing, and then cohere once again into something both familiar and unknown. SHE CALLED HERSELF a minor writer. “I’m no Tolstoy,” said this woman whose parents named her after a character from War and Peace. One wishes Natalia Ginzburg hadn’t apologized for her gifts. Wishes that she had luxuriated in her standing as one of Italy’s finest postwar writers. The fact that her various novels, novellas, and essays are flying back into print—some freshly translated—thirty years after her passing is not unrelated to the extravagant success of the other Italian, the one whose books have become the stuff of prestige television. Ginzburg, alas, has no HBO series attached to her name, but surely her estate profits from the fumes of Ferrante fever. As publishers scramble to chart distinguished genealogies of Italian women writers, we are invited to “discover” Ginzburg’s work in essays like this one. As though it had not been hiding in plain sight for decades.

SHE CALLED HERSELF a minor writer. “I’m no Tolstoy,” said this woman whose parents named her after a character from War and Peace. One wishes Natalia Ginzburg hadn’t apologized for her gifts. Wishes that she had luxuriated in her standing as one of Italy’s finest postwar writers. The fact that her various novels, novellas, and essays are flying back into print—some freshly translated—thirty years after her passing is not unrelated to the extravagant success of the other Italian, the one whose books have become the stuff of prestige television. Ginzburg, alas, has no HBO series attached to her name, but surely her estate profits from the fumes of Ferrante fever. As publishers scramble to chart distinguished genealogies of Italian women writers, we are invited to “discover” Ginzburg’s work in essays like this one. As though it had not been hiding in plain sight for decades. The Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk was, in 2019, a youthful

The Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk was, in 2019, a youthful  Being a human is tricky. There are any number of unwritten rules and social cues that we have to learn as we go, but that we ultimately learn to take for granted. Camilla Pang, who was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder at age eight, had a harder time than most, as she didn’t easily perceive the rules of etiquette and relationships that we need to deal with each other. But she ultimately figured them out, with the help of analogies and examples from different fields of science. We talk about these rules, and how science can help us think about them.

Being a human is tricky. There are any number of unwritten rules and social cues that we have to learn as we go, but that we ultimately learn to take for granted. Camilla Pang, who was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder at age eight, had a harder time than most, as she didn’t easily perceive the rules of etiquette and relationships that we need to deal with each other. But she ultimately figured them out, with the help of analogies and examples from different fields of science. We talk about these rules, and how science can help us think about them. According to a number of

According to a number of  David Byrne is all about connectedness these days. “Everybody’s

David Byrne is all about connectedness these days. “Everybody’s Researchers have explored the cellular changes that occur in human mammary tissue in lactating and non-lactating women, offering insight into the relationship between pregnancy, lactation, and breast cancer. The study was led by researchers from the Wellcome-MRC Cambridge Stem Cell Institute (CSCI) and the Department of Pharmacology at the University of Cambridge. Breast tissue is dynamic, changing over time during puberty, pregnancy, breastfeeding, and aging. The paper, published today in the journal Nature Communications, focuses on the changes that take place during lactation by investigating

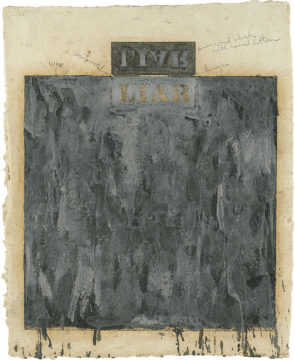

Researchers have explored the cellular changes that occur in human mammary tissue in lactating and non-lactating women, offering insight into the relationship between pregnancy, lactation, and breast cancer. The study was led by researchers from the Wellcome-MRC Cambridge Stem Cell Institute (CSCI) and the Department of Pharmacology at the University of Cambridge. Breast tissue is dynamic, changing over time during puberty, pregnancy, breastfeeding, and aging. The paper, published today in the journal Nature Communications, focuses on the changes that take place during lactation by investigating  In contrast with this array of translucence, viscosity, gleam, Johns exploits the matte, the opaque, the alkaline. His wax encaustic, charcoal, grease, paint stick all militate—it would seem—against sheen.

In contrast with this array of translucence, viscosity, gleam, Johns exploits the matte, the opaque, the alkaline. His wax encaustic, charcoal, grease, paint stick all militate—it would seem—against sheen. McLuhan’s impact on journalism was significant. His message was that all the techniques and values of Victorian liberal journalism should be discarded. The old-fashioned search for truth, using the tools of balance, objectivity, and impartiality, no longer applied. Although greeted with indifference or derision by older journalists, McLuhan’s insight was a Damascene moment for many young writers. As one underground journalist explained in 1966:

McLuhan’s impact on journalism was significant. His message was that all the techniques and values of Victorian liberal journalism should be discarded. The old-fashioned search for truth, using the tools of balance, objectivity, and impartiality, no longer applied. Although greeted with indifference or derision by older journalists, McLuhan’s insight was a Damascene moment for many young writers. As one underground journalist explained in 1966: In the fall

In the fall Mis- and disinformation, partisanship and polarization, crisis points and public trust—the big problems of 2022 were tackled by Walter Lippmann in his book

Mis- and disinformation, partisanship and polarization, crisis points and public trust—the big problems of 2022 were tackled by Walter Lippmann in his book  So without further ado, I decided to try to crawl. I managed to plant my elbows securely but not my knees, and then nailed my knees but not my elbows. This happened several times. I turned over repeatedly on the floor, remembering how I’d rolled down sand dunes at the beach as a child. I lay on my back and managed to drag myself over the floor with my heels, in a kind of inverse crawl. I lay on my belly again and tried using my toes and elbows, but I couldn’t move forward: a slug would have beat me in a hundred-centimeter sprint. Then I realized, or discovered, that I had never crawled as a baby. I’d asked my mother about this recently on the phone. “I’m sure you did. All children crawl,” she said. It bugged me that she didn’t remember. She remembered that I learned to talk very early (she said this as though referring to an incurable disease) and that I started walking before I turned one, but she didn’t have a memory of me crawling. “All children crawl,” she told me, but no, Mom: not all of them do.

So without further ado, I decided to try to crawl. I managed to plant my elbows securely but not my knees, and then nailed my knees but not my elbows. This happened several times. I turned over repeatedly on the floor, remembering how I’d rolled down sand dunes at the beach as a child. I lay on my back and managed to drag myself over the floor with my heels, in a kind of inverse crawl. I lay on my belly again and tried using my toes and elbows, but I couldn’t move forward: a slug would have beat me in a hundred-centimeter sprint. Then I realized, or discovered, that I had never crawled as a baby. I’d asked my mother about this recently on the phone. “I’m sure you did. All children crawl,” she said. It bugged me that she didn’t remember. She remembered that I learned to talk very early (she said this as though referring to an incurable disease) and that I started walking before I turned one, but she didn’t have a memory of me crawling. “All children crawl,” she told me, but no, Mom: not all of them do. G

G