The Mushrooms of Donbas

….—excerpt

. . . and what are we going to tell our children,

how are we going to look them in the eye?

There are just things you have to answer for, things

you can’t just let go.

You are responsible for your penicillin,

and I am responsible for mine.

In a word, we just fought for our mushroom plantations. There we

beat them. And when they fell on the warm hearts of the mushrooms

we thought:

Everything that you make with your hands, works for you.

Everything that reaches your conscience beats

in rhythm with your heart.

We stayed on this land, so that it wouldn’t be far

for our children to visit our graves.

This is our island of freedom

our expanded

village consciousness.

Penicillin and Kalashnikovs – two symbols of struggle,

the Castro of Donbas leads the partisans

through the fog-covered mushroom plantations

to the Azov Sea.

“You know,” he told me, “at night, when everyone falls asleep

and the dark land sucks up the fog,

I feel how the earth moves around the sun, even in my dreams

I listen, listen to how they grow –

the mushrooms of Donbas, silent chimeras of the night,

emerging out of the emptiness, growing out of hard coal,

till hearts stand still, like elevators in buildings at night,

the mushrooms of Donbas grow and grow, never letting the discouraged

and condemned die of grief,

because, man, as long as we’re together,

there’s someone to dig up this earth,

and find in its warm innards

the black stuff of death

the black stuff of life.

by Serhiy Zhadan

from Maradona

Publisher: Folio, Kharkiv, 2007

Translation: Virlana Tkacz and Wanda Phipps, 2011

Entire poem in translation and original Ukranian: here

Even after vaccination, severely immunocompromised people face substantial risk. For example, when researchers measured mortality of fully vaccinated solid organ transplant recipients, they found that, of those who suffered breakthrough infections, nearly one in 10 died. (Notably, this analysis predated widespread use of helpful boosters.)

Even after vaccination, severely immunocompromised people face substantial risk. For example, when researchers measured mortality of fully vaccinated solid organ transplant recipients, they found that, of those who suffered breakthrough infections, nearly one in 10 died. (Notably, this analysis predated widespread use of helpful boosters.)

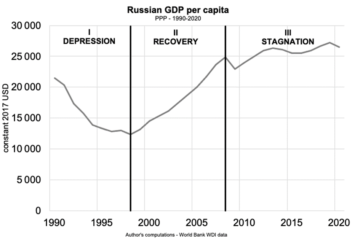

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and ongoing responses by the global community have prompted renewed scrutiny of glaring energy and resource security gaps in the post-Cold War era. War, of course, is not new, nor is Russia’s aggression a unique threat to global energy security or decarbonization. However, as a nuclear-armed and energy export-intensive state engaged in an unprovoked attack on a neighboring country, Russia’s actions do pose novel challenges to national energy, security, and climate priorities.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and ongoing responses by the global community have prompted renewed scrutiny of glaring energy and resource security gaps in the post-Cold War era. War, of course, is not new, nor is Russia’s aggression a unique threat to global energy security or decarbonization. However, as a nuclear-armed and energy export-intensive state engaged in an unprovoked attack on a neighboring country, Russia’s actions do pose novel challenges to national energy, security, and climate priorities.

Dominik A. Leusder in n+1:

Dominik A. Leusder in n+1: Cedric Durand in the New Left Review’s Sidecar:

Cedric Durand in the New Left Review’s Sidecar: Quinn Slobodian in Democracy:

Quinn Slobodian in Democracy: In her theory of writing, Ferrante stands opposed to someone like Joan Didion. Didion famously insisted that she wrote in order to find out what she thought. (“Had I been blessed with even limited access to my own mind there would have been no reason to write.”) In Ferrante’s case, the act is a flawed transcription of what she calls “the brain wave.” For Didion, everything was gained in the voyage from mind to pen; for Ferrante, much goes missing.

In her theory of writing, Ferrante stands opposed to someone like Joan Didion. Didion famously insisted that she wrote in order to find out what she thought. (“Had I been blessed with even limited access to my own mind there would have been no reason to write.”) In Ferrante’s case, the act is a flawed transcription of what she calls “the brain wave.” For Didion, everything was gained in the voyage from mind to pen; for Ferrante, much goes missing. Offering a wealth of examples ranging from cannibal spiders to sex-switching reef fish, Cooke dismantles a mass of misconceptions about binary sex roles, many of which can be traced back to that beloved bearded icon, Charles Darwin. According to Darwinian dogma, male animals fight one another for possession of females, “perform strange tactics” and mate promiscuously, propelled by a biological imperative to spread their abundant seed. Females are monogamous and passive; they wait patiently for their large, energy-rich eggs to be fertilised by cheap and tiny sperm, then selflessly give their all to their offspring.

Offering a wealth of examples ranging from cannibal spiders to sex-switching reef fish, Cooke dismantles a mass of misconceptions about binary sex roles, many of which can be traced back to that beloved bearded icon, Charles Darwin. According to Darwinian dogma, male animals fight one another for possession of females, “perform strange tactics” and mate promiscuously, propelled by a biological imperative to spread their abundant seed. Females are monogamous and passive; they wait patiently for their large, energy-rich eggs to be fertilised by cheap and tiny sperm, then selflessly give their all to their offspring. I find it difficult to imagine being a surgeon in the conditions in which my predecessors had to work — gloveless, covered in blood, with patients physically tied down and screaming in pain, not to mention a postoperative mortality of almost 50 percent. And yet in “Empire of the Scalpel,” Ira Rutkow quotes the 18th-century English surgeon William Cheselden, who wrote of himself: “No one ever endured more anxiety and sickness before an operation, yet from the time that I began to operate, all uneasiness ceased … [I was] never ruffled or disconcerted and [my hand] … never trembled during an operation.”

I find it difficult to imagine being a surgeon in the conditions in which my predecessors had to work — gloveless, covered in blood, with patients physically tied down and screaming in pain, not to mention a postoperative mortality of almost 50 percent. And yet in “Empire of the Scalpel,” Ira Rutkow quotes the 18th-century English surgeon William Cheselden, who wrote of himself: “No one ever endured more anxiety and sickness before an operation, yet from the time that I began to operate, all uneasiness ceased … [I was] never ruffled or disconcerted and [my hand] … never trembled during an operation.” The best moments on television shine for lots of different reasons. They can be heartwarming, tearjerking, shocking – or, sometimes, so viscerally uncomfortable that they keep replaying in your head long after the episode or even the series is over.

The best moments on television shine for lots of different reasons. They can be heartwarming, tearjerking, shocking – or, sometimes, so viscerally uncomfortable that they keep replaying in your head long after the episode or even the series is over. There is something that especially delights me about the story, and then also the paintings, of Vivian Suter, who happens to have a show up right now at the extension of the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, the extension being a large building in Retiro Park called the Velazquez Palace, which is packed full right now with hundreds of paintings by Vivian Suter, more paintings than I have maybe ever seen in a one-person show and this, indeed, is part of the delight of Vivian Suter, part of what is so fascinating about Vivian Suter, namely, that she doesn’t seem to care about her canvases all that much and so you can pack a smallish palace with hundreds of them, hanging all over the place, lying in piles, whatever, some of them covered in dirt and other detritus and a couple of them marked with what seems to be the footprints of dogs, pawprints I guess.

There is something that especially delights me about the story, and then also the paintings, of Vivian Suter, who happens to have a show up right now at the extension of the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, the extension being a large building in Retiro Park called the Velazquez Palace, which is packed full right now with hundreds of paintings by Vivian Suter, more paintings than I have maybe ever seen in a one-person show and this, indeed, is part of the delight of Vivian Suter, part of what is so fascinating about Vivian Suter, namely, that she doesn’t seem to care about her canvases all that much and so you can pack a smallish palace with hundreds of them, hanging all over the place, lying in piles, whatever, some of them covered in dirt and other detritus and a couple of them marked with what seems to be the footprints of dogs, pawprints I guess. Today, The Open Society and Its Enemies is perhaps best remembered for two things: Karl Popper’s coinage of the terms “open society” and “closed society,” and his scorched-earth attack on Plato as the original architect of the latter. For Popper, Plato was the first and the most influential authoritarian thinker. (Popper’s analogous charges against Aristotle, Marx, and Hegel have not proven as memorable.)

Today, The Open Society and Its Enemies is perhaps best remembered for two things: Karl Popper’s coinage of the terms “open society” and “closed society,” and his scorched-earth attack on Plato as the original architect of the latter. For Popper, Plato was the first and the most influential authoritarian thinker. (Popper’s analogous charges against Aristotle, Marx, and Hegel have not proven as memorable.) Curator Wolf Burchard has astutely understood that some of the Met’s least appreciated objects have become cultural icons, just not in the way the museum usually presents them. The Met owns one of the world’s best collections of eighteenth-century “decorative arts”; they usually languish in the museum’s emptiest galleries. Yet when Disney animated them into characters like the candlestick Lumiére in Beauty and the Beast or into scenes in Cinderella (1950), which features the heroine’s rags spiraling into a court gown, they have beguiled mass audiences. The Met rightly makes the essential formal point that Disney was inspired by the inherent animation of Rococo design, its kinetic furniture equipped with multiple moving parts and frothy ornament. To help us understand how widely this impulse pervaded eighteenth-century European culture, the museum cleverly displays a copy of a novel, Le Sopha: Conte Moral. The 1742 best seller, like many stories of its time, revolves around a thing that thinks.

Curator Wolf Burchard has astutely understood that some of the Met’s least appreciated objects have become cultural icons, just not in the way the museum usually presents them. The Met owns one of the world’s best collections of eighteenth-century “decorative arts”; they usually languish in the museum’s emptiest galleries. Yet when Disney animated them into characters like the candlestick Lumiére in Beauty and the Beast or into scenes in Cinderella (1950), which features the heroine’s rags spiraling into a court gown, they have beguiled mass audiences. The Met rightly makes the essential formal point that Disney was inspired by the inherent animation of Rococo design, its kinetic furniture equipped with multiple moving parts and frothy ornament. To help us understand how widely this impulse pervaded eighteenth-century European culture, the museum cleverly displays a copy of a novel, Le Sopha: Conte Moral. The 1742 best seller, like many stories of its time, revolves around a thing that thinks.