Alison Bentley in Nature:

Six boxes of wheat seed sit in our cold store. This is the first time in a decade that my team has not been able to send to Ukraine the improved germplasm we’ve developed as part of the Global Wheat Program at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center in Texcoco, Mexico. International postal and courier services are suspended. The seed had boosted productivity year on year in the country, which is now being devastated by war.

Six boxes of wheat seed sit in our cold store. This is the first time in a decade that my team has not been able to send to Ukraine the improved germplasm we’ve developed as part of the Global Wheat Program at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center in Texcoco, Mexico. International postal and courier services are suspended. The seed had boosted productivity year on year in the country, which is now being devastated by war.

Our work builds on the legacy of Norman Borlaug, who catalysed the Green Revolution and staved off famine in south Asia in the 1970s. Thanks to him, I see how a grain of wheat can affect the world.

Among the horrifying humanitarian consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are deeply troubling short-, medium- and long-term disruptions to the global food supply. Ukraine and Russia contribute nearly one-third of all wheat exports (as well as almost one-third of the world’s barley and one-fifth of its corn, providing an estimated 11% of the world’s calories). Lebanon, for instance, gets 80% of its wheat from Ukraine alone.

More here.

Today I decided that I will record thoughts against death as they happen to occur to me, without any kind of structure and without submitting them to any tyrannical plan. I cannot let this war pass without hammering out a weapon within my heart that will conquer death. It will be tortuous and insidious, perfectly suited to it. In better times I would wield it as a joke or a brazen threat. I think of the act of slaying death as a masquerade. Employing fifty disguises and numerous plots is how I’d do it. But now death has switched masks yet again. No longer content with its ongoing daily victory, death grabs whatever it can. It riddles the air and the seas; whether the smallest or the largest, it doesn’t matter, for it wants it all, and it has no time for anything else. Nor do I have any time. I have to nab it wherever I can, nail it here and there in first-rate sentences. At the moment I cannot house it in any coffins, much less embalm it, much less lay the embalmed to rest in a gated mausoleum.

Today I decided that I will record thoughts against death as they happen to occur to me, without any kind of structure and without submitting them to any tyrannical plan. I cannot let this war pass without hammering out a weapon within my heart that will conquer death. It will be tortuous and insidious, perfectly suited to it. In better times I would wield it as a joke or a brazen threat. I think of the act of slaying death as a masquerade. Employing fifty disguises and numerous plots is how I’d do it. But now death has switched masks yet again. No longer content with its ongoing daily victory, death grabs whatever it can. It riddles the air and the seas; whether the smallest or the largest, it doesn’t matter, for it wants it all, and it has no time for anything else. Nor do I have any time. I have to nab it wherever I can, nail it here and there in first-rate sentences. At the moment I cannot house it in any coffins, much less embalm it, much less lay the embalmed to rest in a gated mausoleum. It is interesting to see how insistently Clark describes her artistic practice as oriented toward an “ethico-religious” goal—and not just to the making of “one surface or another”—as there are few signs of that central preoccupation in her earlier writings. This confession, I think, should be read as an exercise in self-criticism. In confronting Mondrian, Clark appears to be confronting herself, although at the same time she seems to expect recognition from a person she considers to be a kindred spirit—another mystic. To describe Mondrian as a mystic is of course not uncommon. Yet the term has been used rather loosely, either to refer to Mondrian’s interest in esotericism (especially the Theosophical teachings of Madame Blavatsky) or, more generally, to the sense of spirituality that infused many early projects of abstraction. In her letter, however, Clark invokes a rather different notion of mysticism. Neither school nor doctrine is involved in it but rather a particular kind of experience.

It is interesting to see how insistently Clark describes her artistic practice as oriented toward an “ethico-religious” goal—and not just to the making of “one surface or another”—as there are few signs of that central preoccupation in her earlier writings. This confession, I think, should be read as an exercise in self-criticism. In confronting Mondrian, Clark appears to be confronting herself, although at the same time she seems to expect recognition from a person she considers to be a kindred spirit—another mystic. To describe Mondrian as a mystic is of course not uncommon. Yet the term has been used rather loosely, either to refer to Mondrian’s interest in esotericism (especially the Theosophical teachings of Madame Blavatsky) or, more generally, to the sense of spirituality that infused many early projects of abstraction. In her letter, however, Clark invokes a rather different notion of mysticism. Neither school nor doctrine is involved in it but rather a particular kind of experience. As the new Faith in America survey by Deseret News & Marist College highlights, the basic understanding of the role of religion in a secular democracy has become so polarized that 70% of Republicans believe that religion should influence a person’s political values, where as only 28% of Democrats and 45% of independents share that view. Republicans and Democrats, liberals and conservatives, also do not consume the same sources of information about news and politics. Conservatives now inhabit their own self-created media echo chamber, which functions as a type of lie-filled and toxic closed episteme and sealed-off universe. The creation of such an alternate reality is an important attribute of fascism, in which truth itself must be destroyed and replaced with fantasies and fictions in support of the leader and his movement.

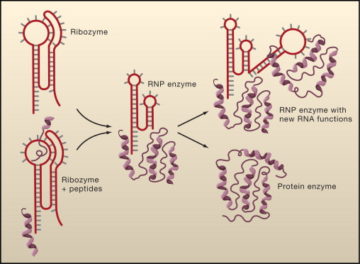

As the new Faith in America survey by Deseret News & Marist College highlights, the basic understanding of the role of religion in a secular democracy has become so polarized that 70% of Republicans believe that religion should influence a person’s political values, where as only 28% of Democrats and 45% of independents share that view. Republicans and Democrats, liberals and conservatives, also do not consume the same sources of information about news and politics. Conservatives now inhabit their own self-created media echo chamber, which functions as a type of lie-filled and toxic closed episteme and sealed-off universe. The creation of such an alternate reality is an important attribute of fascism, in which truth itself must be destroyed and replaced with fantasies and fictions in support of the leader and his movement. It is common to observe that one of the greatest unsolved questions of science is how life began. This is a distinct question from how the diversity of the species of living things emerged. It is well established that once life had established a self-replicating system capable of generating some variation, that evolutionary forces would kick in and could, and in fact did, create all life on Earth. But we are a long way from reverse-engineering in any detail how those first organic molecules transitioned from chemistry to life.

It is common to observe that one of the greatest unsolved questions of science is how life began. This is a distinct question from how the diversity of the species of living things emerged. It is well established that once life had established a self-replicating system capable of generating some variation, that evolutionary forces would kick in and could, and in fact did, create all life on Earth. But we are a long way from reverse-engineering in any detail how those first organic molecules transitioned from chemistry to life. Knopf announced March 8 that it will

Knopf announced March 8 that it will  When we teach people how to avoid falling victim to phishing sites, we usually advise closely inspecting the address bar to make sure it does contain HTTPS and that it doesn’t contain suspicious domains such as google.evildomain.com or substitute letters such as g00gle.com. But what if someone found a way to phish passwords using a malicious site that didn’t contain these telltale signs?

When we teach people how to avoid falling victim to phishing sites, we usually advise closely inspecting the address bar to make sure it does contain HTTPS and that it doesn’t contain suspicious domains such as google.evildomain.com or substitute letters such as g00gle.com. But what if someone found a way to phish passwords using a malicious site that didn’t contain these telltale signs?

In 2013, a charismatic Mexican doctor took the stage at Burning Man, in Nevada, to give a tedx talk on what he called “the ultimate experience.” The doctor’s name was Octavio Rettig, and he would soon become known by his first name alone, like some pop diva or soccer star. He told the crowd that, years earlier, he had overcome a crack addiction by using a powerful psychedelic substance produced by toads in the Sonoran Desert. Afterward, he shared “toad medicine” with a tribal community in northern Mexico, where the rise of narco-trafficking had brought on a methamphetamine crisis. Through this work, he came to believe that smoking toad, as the practice is called, was an ancient Mesoamerican ritual—a “unique toadal language,” shared by Mayans and Aztecs—that had been stamped out during the colonial era. He announced that he’d restored a lost tradition, and that he had a duty to share it with others. “Sooner or later, everyone in the world will have this experience,” he told an interviewer after the talk.

In 2013, a charismatic Mexican doctor took the stage at Burning Man, in Nevada, to give a tedx talk on what he called “the ultimate experience.” The doctor’s name was Octavio Rettig, and he would soon become known by his first name alone, like some pop diva or soccer star. He told the crowd that, years earlier, he had overcome a crack addiction by using a powerful psychedelic substance produced by toads in the Sonoran Desert. Afterward, he shared “toad medicine” with a tribal community in northern Mexico, where the rise of narco-trafficking had brought on a methamphetamine crisis. Through this work, he came to believe that smoking toad, as the practice is called, was an ancient Mesoamerican ritual—a “unique toadal language,” shared by Mayans and Aztecs—that had been stamped out during the colonial era. He announced that he’d restored a lost tradition, and that he had a duty to share it with others. “Sooner or later, everyone in the world will have this experience,” he told an interviewer after the talk. During a workshop last fall at the Vatican, Stanislas Dehaene, a cognitive neuroscientist with the Collège de France, gave a presentation chronicling his quest to understand what makes humans — for better or worse — so special. Dr. Dehaene has spent decades probing the evolutionary roots of our mathematical instinct; this was the subject of his 1996 book, “

During a workshop last fall at the Vatican, Stanislas Dehaene, a cognitive neuroscientist with the Collège de France, gave a presentation chronicling his quest to understand what makes humans — for better or worse — so special. Dr. Dehaene has spent decades probing the evolutionary roots of our mathematical instinct; this was the subject of his 1996 book, “ IN AN ESSAY ABOUT NATALIA GINZBURG, the Chilean novelist and critic Alejandro Zambra writes, “When someone repeats a story we presume they don’t remember that they’ve already told it, but often we repeat stories consciously, because we are unable to repress the desire, the joy of telling them again.” Of course the compulsion to retell a story is not always situated in joy’s lofty terrain. We might repeat a story in the hopes of shrinking it to a manageable bite, or because it reminds us of another story, or to shine up disagreeable aspects of our lives, or to mock it, perhaps secretly wishing it will deflect mockery from our more vulnerable, foolish selves. All of this is present, for me, in Zambra’s writing, and has been since the first time I read his work, which was around four years ago on the recommendation of someone I’d been on a few dates with. In the desultory landscapes of Bushwick and Greenpoint the snow was comically high, but only in retrospect. Everyone suddenly knew what an NDA was and wondered how to get out of theirs. We talked haughtily and agreeably about literature, and then I said something cruel about his dog, which turned out really to be the only thing, years later, we still talked about. The dog was named after a writer who composed several books of poetry but is best known for his novels.

IN AN ESSAY ABOUT NATALIA GINZBURG, the Chilean novelist and critic Alejandro Zambra writes, “When someone repeats a story we presume they don’t remember that they’ve already told it, but often we repeat stories consciously, because we are unable to repress the desire, the joy of telling them again.” Of course the compulsion to retell a story is not always situated in joy’s lofty terrain. We might repeat a story in the hopes of shrinking it to a manageable bite, or because it reminds us of another story, or to shine up disagreeable aspects of our lives, or to mock it, perhaps secretly wishing it will deflect mockery from our more vulnerable, foolish selves. All of this is present, for me, in Zambra’s writing, and has been since the first time I read his work, which was around four years ago on the recommendation of someone I’d been on a few dates with. In the desultory landscapes of Bushwick and Greenpoint the snow was comically high, but only in retrospect. Everyone suddenly knew what an NDA was and wondered how to get out of theirs. We talked haughtily and agreeably about literature, and then I said something cruel about his dog, which turned out really to be the only thing, years later, we still talked about. The dog was named after a writer who composed several books of poetry but is best known for his novels. The Spanish pop star Rosalía is the rarest kind of modern musician: a relentlessly innovative aesthetic omnivore who also happens to have a decade of Old World, genre-specific formal training under her belt. As a teen-ager living on the outskirts of Barcelona, she was introduced to flamenco music by a group of friends from Andalusia, a region in the south of Spain where the style originated. Hearing the music of the flamenco giant Camarón de la Isla, she once told El Mundo, made her feel as if her “head exploded.” The discovery prompted Rosalía to throw her entire being into the practice of flamenco, an elemental genre built around hand-clapping, acoustic guitar, and a fierce and improvisational vocal style. She took flamenco dance classes; she learned guitar and piano, and, most important, she enrolled at the Catalonia College of Music, under the tutelage of the decorated flamenco singer and teacher Chiqui de la Línea. Pioneered by the Romani people (the term for Spain’s Gypsy population), the vocals of traditional flamenco are like kites—they follow unpredictable and precarious paths but sound as if they’re being buoyed by an invisible force of nature. Rosalía did not merely train to become a singer; she strove to master the intense and distinctive styles of flamenco’s beloved cantaores and cantaoras.

The Spanish pop star Rosalía is the rarest kind of modern musician: a relentlessly innovative aesthetic omnivore who also happens to have a decade of Old World, genre-specific formal training under her belt. As a teen-ager living on the outskirts of Barcelona, she was introduced to flamenco music by a group of friends from Andalusia, a region in the south of Spain where the style originated. Hearing the music of the flamenco giant Camarón de la Isla, she once told El Mundo, made her feel as if her “head exploded.” The discovery prompted Rosalía to throw her entire being into the practice of flamenco, an elemental genre built around hand-clapping, acoustic guitar, and a fierce and improvisational vocal style. She took flamenco dance classes; she learned guitar and piano, and, most important, she enrolled at the Catalonia College of Music, under the tutelage of the decorated flamenco singer and teacher Chiqui de la Línea. Pioneered by the Romani people (the term for Spain’s Gypsy population), the vocals of traditional flamenco are like kites—they follow unpredictable and precarious paths but sound as if they’re being buoyed by an invisible force of nature. Rosalía did not merely train to become a singer; she strove to master the intense and distinctive styles of flamenco’s beloved cantaores and cantaoras. A

A When we experience shame, we feel bad; and when we inflict shame, we feel good. Those seem to be among the few points of consensus when it comes to what the historian Peter N. Stearns calls a “disputed emotion.” Unlike fear or anger, shame is “self-conscious”; it doesn’t erupt so much as coil around itself. It requires an awareness of others and their disapproval, and it has to be learned. Aristotle thought of it as fundamental to ethical behavior; Confucius saw it as essential to social order.

When we experience shame, we feel bad; and when we inflict shame, we feel good. Those seem to be among the few points of consensus when it comes to what the historian Peter N. Stearns calls a “disputed emotion.” Unlike fear or anger, shame is “self-conscious”; it doesn’t erupt so much as coil around itself. It requires an awareness of others and their disapproval, and it has to be learned. Aristotle thought of it as fundamental to ethical behavior; Confucius saw it as essential to social order. When did it become as hard to imagine what a good—or at least not as bad—internet might look like as to picture a world without the internet at all? Social-media mobs, conspiratorial thinking, deadly disinformation campaigns, gadget addiction, the funk of mass attention-deficit disorder: World-Wide-Web woes comprise a growth economy. The less acute but vague unease of our encounter with digital technology isn’t much alleviated by the possibility of imagining a truly off-the-grid alternative. (That a bit of shorthand like “off the grid” exists to describe a break from tech is as much a symptom of the problem as anything.) Perhaps to say that we feel backed into a corner by a claque of devices of our own making is not really to say much of anything at all.

When did it become as hard to imagine what a good—or at least not as bad—internet might look like as to picture a world without the internet at all? Social-media mobs, conspiratorial thinking, deadly disinformation campaigns, gadget addiction, the funk of mass attention-deficit disorder: World-Wide-Web woes comprise a growth economy. The less acute but vague unease of our encounter with digital technology isn’t much alleviated by the possibility of imagining a truly off-the-grid alternative. (That a bit of shorthand like “off the grid” exists to describe a break from tech is as much a symptom of the problem as anything.) Perhaps to say that we feel backed into a corner by a claque of devices of our own making is not really to say much of anything at all.