Benjamin Cooper in The Common Reader:

War is a not a word that communicates much. It wants to, but quickly the gruff sound deteriorates into an abstraction and nothing more. War. War. Like love, truth, or beauty, we say the word but cannot see it. The gut does not believe. To title a book War as Margaret MacMillan, the distinguished historian, has done, is to attempt to assert control over the very term itself. As a result, even before the prose begins, War: How Conflict Shaped Us promises to be a revelation: here, war will be understood at last. Such authoritativeness is a noble pursuit, and MacMillan joins others in recent years such as Sebastian Junger and Jeremy Black in a frantic effort to articulate a unified field theory of war before it is too late.¹ “We face the prospect of the end of humanity itself,” MacMillan concludes, if we fail to demystify war in our current moment. (289) That is the project, and given the book’s critical and popular praise from notable figures such as war journalist Dexter Filkins, former National Security Director H.R. McMaster, and former Secretary of State George Schultz, readers might feel it has done its work. I am not so sure, which is not a criticism of MacMillan’s book so much as it is a lament about the relentless inscrutability of war both as an object of academic study and as a lived experience that resists expression.

War is a not a word that communicates much. It wants to, but quickly the gruff sound deteriorates into an abstraction and nothing more. War. War. Like love, truth, or beauty, we say the word but cannot see it. The gut does not believe. To title a book War as Margaret MacMillan, the distinguished historian, has done, is to attempt to assert control over the very term itself. As a result, even before the prose begins, War: How Conflict Shaped Us promises to be a revelation: here, war will be understood at last. Such authoritativeness is a noble pursuit, and MacMillan joins others in recent years such as Sebastian Junger and Jeremy Black in a frantic effort to articulate a unified field theory of war before it is too late.¹ “We face the prospect of the end of humanity itself,” MacMillan concludes, if we fail to demystify war in our current moment. (289) That is the project, and given the book’s critical and popular praise from notable figures such as war journalist Dexter Filkins, former National Security Director H.R. McMaster, and former Secretary of State George Schultz, readers might feel it has done its work. I am not so sure, which is not a criticism of MacMillan’s book so much as it is a lament about the relentless inscrutability of war both as an object of academic study and as a lived experience that resists expression.

More here.

They were in lines extending as far as the eye could see, stretching across the horizon and toward the Promised Land. Dutifully, though with growing impatience and anxiety, they were waiting their turn to enter the fabled American Dreamland, where all who worked hard would be assured well-paid jobs and comfortable homes where well-adjusted children would flourish, and smile their winning smiles.

They were in lines extending as far as the eye could see, stretching across the horizon and toward the Promised Land. Dutifully, though with growing impatience and anxiety, they were waiting their turn to enter the fabled American Dreamland, where all who worked hard would be assured well-paid jobs and comfortable homes where well-adjusted children would flourish, and smile their winning smiles. A fully paralyzed man with ALS, or

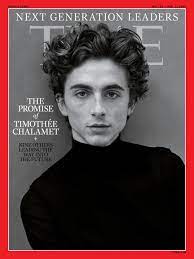

A fully paralyzed man with ALS, or  If Chalamet—whom most people call, affectionately, Timmy—sees himself as off-center, so far it’s working. He’s back in New York for the Met Gala, which he’s co-chairing alongside

If Chalamet—whom most people call, affectionately, Timmy—sees himself as off-center, so far it’s working. He’s back in New York for the Met Gala, which he’s co-chairing alongside  Konstantin Olmezov in n+1:

Konstantin Olmezov in n+1: Rajan Menon in Boston Review:

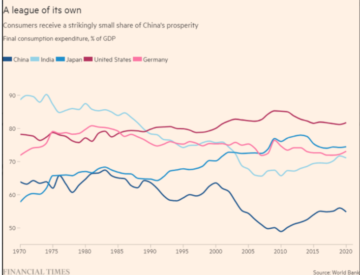

Rajan Menon in Boston Review: Adam Tooze debates Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu on whether China can make the adjustments necessary to sustain growth.

Adam Tooze debates Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu on whether China can make the adjustments necessary to sustain growth.  James Meadway in Sidecar:

James Meadway in Sidecar: But as Green says, and his book splendidly demonstrates, “what has disappeared beneath sea can rebuild itself in the mind”. Since the 13th century, when the Suffolk coastline by Dunwich began to be seriously gnawed by the waves, thousands of settlements have disappeared from our maps. It is the untold story of these lost communities – “Britain’s shadow topography” – that has become Green’s obsession. He disinters their rich history and reimagines the lives of those who walked their streets, revealing “tales of human perseverance, obsession, resistance and reconciliation”. By doing so, he makes tangible the tragedy of their loss and the threat we all face from the climate crisis on these storm-tossed islands.

But as Green says, and his book splendidly demonstrates, “what has disappeared beneath sea can rebuild itself in the mind”. Since the 13th century, when the Suffolk coastline by Dunwich began to be seriously gnawed by the waves, thousands of settlements have disappeared from our maps. It is the untold story of these lost communities – “Britain’s shadow topography” – that has become Green’s obsession. He disinters their rich history and reimagines the lives of those who walked their streets, revealing “tales of human perseverance, obsession, resistance and reconciliation”. By doing so, he makes tangible the tragedy of their loss and the threat we all face from the climate crisis on these storm-tossed islands. In 1966, Stewart Brand was an impresario of Bay Area counterculture. As the host of an extravaganza of music and psychedelic simulation called the Trips Festival, he was, according to

In 1966, Stewart Brand was an impresario of Bay Area counterculture. As the host of an extravaganza of music and psychedelic simulation called the Trips Festival, he was, according to  Carl Erik Fisher’s new book, “The Urge: Our History of Addiction,” follows two journeys: One is a memoir of his own addiction to alcohol (he grew up with two alcoholic parents), and the other is a detailed overview of the approaches that have been used to understand, control and treat addiction over time. This last includes the relatively contemporary idea of “recovery,” which suggests that it is possible, with the right medications, such as naloxone, buprenorphine or methadone, and thoughtful care, to break its hold.

Carl Erik Fisher’s new book, “The Urge: Our History of Addiction,” follows two journeys: One is a memoir of his own addiction to alcohol (he grew up with two alcoholic parents), and the other is a detailed overview of the approaches that have been used to understand, control and treat addiction over time. This last includes the relatively contemporary idea of “recovery,” which suggests that it is possible, with the right medications, such as naloxone, buprenorphine or methadone, and thoughtful care, to break its hold. Think about a time when you changed your mind. Maybe you heard about a crime, and rushed to judgment about the guilt or innocence of the accused. Perhaps you wanted your country to go to war, and realise now that maybe that was a bad idea. Or possibly you grew up in a religious or partisan household, and switched allegiances when you got older. Part of maturing is developing intellectual humility. You’ve been wrong before; you could be wrong now.

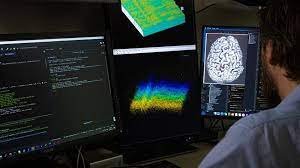

Think about a time when you changed your mind. Maybe you heard about a crime, and rushed to judgment about the guilt or innocence of the accused. Perhaps you wanted your country to go to war, and realise now that maybe that was a bad idea. Or possibly you grew up in a religious or partisan household, and switched allegiances when you got older. Part of maturing is developing intellectual humility. You’ve been wrong before; you could be wrong now. During a workshop last fall at the Vatican, Stanislas Dehaene, a cognitive neuroscientist with the Collège de France, gave a presentation chronicling his quest to understand what makes humans — for better or worse — so special.

During a workshop last fall at the Vatican, Stanislas Dehaene, a cognitive neuroscientist with the Collège de France, gave a presentation chronicling his quest to understand what makes humans — for better or worse — so special.