Sophie Bushwick in Scientific American:

How is a lost tale of chivalry from medieval Europe like an unknown species of animal? According to a new study, the number of both items can be tallied using exactly the same mathematical model. The findings align with existing estimates of lost literature—and suggest that ecological models can be applied to a surprising variety of social science fields.

How is a lost tale of chivalry from medieval Europe like an unknown species of animal? According to a new study, the number of both items can be tallied using exactly the same mathematical model. The findings align with existing estimates of lost literature—and suggest that ecological models can be applied to a surprising variety of social science fields.

Experts know that much fiction from the medieval era (roughly from the beginning of the fifth century A.D. to the end of the 14th century), such as chivalric romances about King Arthur’s court, has disappeared over time. But quantifying that loss is difficult. “One thing we don’t know is … the portion of literature that didn’t survive,” says the new study’s co-author Mike Kestemont, an associate professor in the department of literature at the University of Antwerp in Belgium. Learning about what was lost can teach scholars more about the medieval period, and there are also present-day reasons to value this work, adds co-author Daniel Sawyer, a research fellow in medieval English literature at the University of Oxford. “Thinking about how cultural heritage survives seems like a useful thing to do, because right now—among many other things—that’s one of the important things threatened by things like climate change,” Sawyer says. “In the longer run, we as a species probably need to be thinking about ‘How do we preserve and record what we have?’ And knowing more about what kind of patterns of distribution can help survival of these things is not irrelevant to that.”

More here.

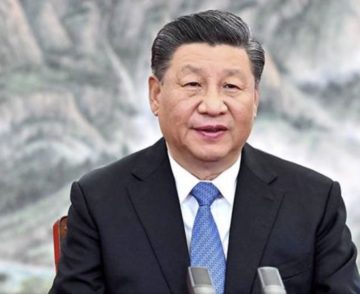

What if China had been open and honest in December 2019? What if the world had reacted as quickly and aggressively in January 2020 as Taiwan did? What if the United States had put appropriate protective measures in place in February 2020, as South Korea did?

What if China had been open and honest in December 2019? What if the world had reacted as quickly and aggressively in January 2020 as Taiwan did? What if the United States had put appropriate protective measures in place in February 2020, as South Korea did? Let me start by saying a few things that seem obvious,” Geoffrey Hinton, “Godfather” of deep learning, and one of the most celebrated scientists of our time, told a leading AI conference in Toronto in 2016. “If you work as a radiologist you’re like the coyote that’s already over the edge of the cliff but hasn’t looked down.” Deep learning is so well-suited to reading images from MRIs and CT scans, he reasoned, that people should “stop training radiologists now” and that it’s “just completely obvious within five years deep learning is going to do better.”

Let me start by saying a few things that seem obvious,” Geoffrey Hinton, “Godfather” of deep learning, and one of the most celebrated scientists of our time, told a leading AI conference in Toronto in 2016. “If you work as a radiologist you’re like the coyote that’s already over the edge of the cliff but hasn’t looked down.” Deep learning is so well-suited to reading images from MRIs and CT scans, he reasoned, that people should “stop training radiologists now” and that it’s “just completely obvious within five years deep learning is going to do better.” A protest movement against the invasion of Ukraine is growing in Russia. Demonstrations were held in 60 cities on March 6 and in 37 on Sunday, spurred in part by calls to turn out from imprisoned opposition leader Alexei Navalny. More than 14,900 people have been detained by security forces and police for protesting, according to

A protest movement against the invasion of Ukraine is growing in Russia. Demonstrations were held in 60 cities on March 6 and in 37 on Sunday, spurred in part by calls to turn out from imprisoned opposition leader Alexei Navalny. More than 14,900 people have been detained by security forces and police for protesting, according to  Like much of the world, I’ve been captivated by adult film actress turned director Stormy Daniels—but not for the usual reasons. Her encounter with former President Donald Trump is the least interesting thing about this otherwise brilliant, original, and deeply fascinating person whose single-minded pursuit to defend her dignity is mostly lost amid a rage of salacious headlines.

Like much of the world, I’ve been captivated by adult film actress turned director Stormy Daniels—but not for the usual reasons. Her encounter with former President Donald Trump is the least interesting thing about this otherwise brilliant, original, and deeply fascinating person whose single-minded pursuit to defend her dignity is mostly lost amid a rage of salacious headlines. If extraterrestrial life is out there — not just microbial slime, but big, complex, macroscopic organisms — what will they be like? Movies have trained us to think that they won’t be that different at all; they’ll even drink and play music at the same cafes that humans frequent. A bit of imagination, however, makes us wonder whether they won’t be completely alien — we have zero data about what extraterrestrial biology could be like, so it makes sense to keep an open mind. Arik Kershenbaum argues for a judicious middle ground. He points to constraints from physics and chemistry, as well as the tendency of evolution to converge toward successful designs, as reasons to think that biologically complex aliens won’t be utterly different from us after all.

If extraterrestrial life is out there — not just microbial slime, but big, complex, macroscopic organisms — what will they be like? Movies have trained us to think that they won’t be that different at all; they’ll even drink and play music at the same cafes that humans frequent. A bit of imagination, however, makes us wonder whether they won’t be completely alien — we have zero data about what extraterrestrial biology could be like, so it makes sense to keep an open mind. Arik Kershenbaum argues for a judicious middle ground. He points to constraints from physics and chemistry, as well as the tendency of evolution to converge toward successful designs, as reasons to think that biologically complex aliens won’t be utterly different from us after all. The Russo-Ukrainian War is the most severe geopolitical conflict since World War II and will result in far greater global consequences than September 11 attacks. At this critical moment, China needs to accurately analyze and assess the direction of the war and its potential impact on the international landscape. At the same time, in order to strive for a relatively favorable external environment, China needs to respond flexibly and make strategic choices that conform to its long-term interests.

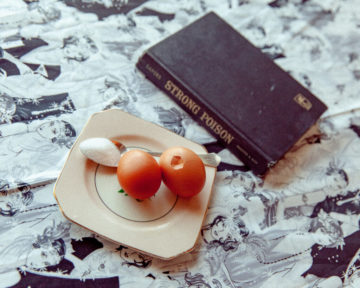

The Russo-Ukrainian War is the most severe geopolitical conflict since World War II and will result in far greater global consequences than September 11 attacks. At this critical moment, China needs to accurately analyze and assess the direction of the war and its potential impact on the international landscape. At the same time, in order to strive for a relatively favorable external environment, China needs to respond flexibly and make strategic choices that conform to its long-term interests. Dorothy Sayers’s Strong Poison opens with a description of a man’s last meal before death. The deceased, Philip Boyes, was a writer with “advanced” ideas, dining at the home of his wealthy great-nephew, Norman Urquhart, a lawyer. A judge tells a jury what he ate: the meal starts with a glass of 1847 oloroso “by way of cocktail,” followed by a cup of cold bouillon—“very strong, good soup, set to a clear jelly”—then turbot with sauce, poulet en casserole, and finally a sweet omelet stuffed with jam and prepared tableside. The point of the description is to show that Boyes couldn’t have been poisoned, since every dish was shared, with the exception of a bottle of Burgundy (Corton), which he drank alone. The judge’s oration is another strike against the accused, a bohemian mystery novelist named Harriet Vane, who saw Boyes on the night he died, and had both motive and opportunity to poison him. Looking on from the audience, the famous amateur detective Lord Peter Wimsey writhes in misery; he believes Harriet Vane is innocent, and he has fallen suddenly and completely in love with her.

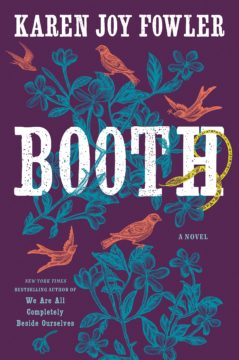

Dorothy Sayers’s Strong Poison opens with a description of a man’s last meal before death. The deceased, Philip Boyes, was a writer with “advanced” ideas, dining at the home of his wealthy great-nephew, Norman Urquhart, a lawyer. A judge tells a jury what he ate: the meal starts with a glass of 1847 oloroso “by way of cocktail,” followed by a cup of cold bouillon—“very strong, good soup, set to a clear jelly”—then turbot with sauce, poulet en casserole, and finally a sweet omelet stuffed with jam and prepared tableside. The point of the description is to show that Boyes couldn’t have been poisoned, since every dish was shared, with the exception of a bottle of Burgundy (Corton), which he drank alone. The judge’s oration is another strike against the accused, a bohemian mystery novelist named Harriet Vane, who saw Boyes on the night he died, and had both motive and opportunity to poison him. Looking on from the audience, the famous amateur detective Lord Peter Wimsey writhes in misery; he believes Harriet Vane is innocent, and he has fallen suddenly and completely in love with her. On 14 April 1865, less than a week after Confederate General Robert E Lee surrendered his army in Virginia and effectively ended the American Civil War, John Wilkes Booth gained entry to the private box at the theatre in Washington, DC, where Abraham Lincoln and his guests were watching a performance of Our American Cousin and shot the president in the head. Lincoln was pronounced dead the next morning. His assassination thrust much of the country into fresh despair and prompted the largest manhunt in American history.

On 14 April 1865, less than a week after Confederate General Robert E Lee surrendered his army in Virginia and effectively ended the American Civil War, John Wilkes Booth gained entry to the private box at the theatre in Washington, DC, where Abraham Lincoln and his guests were watching a performance of Our American Cousin and shot the president in the head. Lincoln was pronounced dead the next morning. His assassination thrust much of the country into fresh despair and prompted the largest manhunt in American history. O

O Two beloved paintings have swapped locations for a while. One went from California to London; the other, from London to California. No passports were involved. But the two museums where the paintings are housed — the Huntington Art Museum near Los Angeles, and London’s National Gallery — are welcoming visitors to see these masterpieces. The best known is a portrait of a rosy-cheeked fellow, maybe 15 years old, in a blue satiny suit with matching blue bows on his shoes.

Two beloved paintings have swapped locations for a while. One went from California to London; the other, from London to California. No passports were involved. But the two museums where the paintings are housed — the Huntington Art Museum near Los Angeles, and London’s National Gallery — are welcoming visitors to see these masterpieces. The best known is a portrait of a rosy-cheeked fellow, maybe 15 years old, in a blue satiny suit with matching blue bows on his shoes. Today’s ‘stack will principally involve “housekeeping”. I said explicitly a week ago that the war in Ukraine has left me literally speechless, and I meant it. I was able to squeeze out some speech a week ago nonetheless, mostly by soldering together various fragments already written, by descending into mean-spiritedness in a vain effort to be funny, by “just saying whatever”. I can’t rely on the strategy of gonzo bricolage week to week, and so today I can only confess the stubborn silence of my “inner voice”, the homunculus who lives inside me and, when things are going right, dictates what I have to say.

Today’s ‘stack will principally involve “housekeeping”. I said explicitly a week ago that the war in Ukraine has left me literally speechless, and I meant it. I was able to squeeze out some speech a week ago nonetheless, mostly by soldering together various fragments already written, by descending into mean-spiritedness in a vain effort to be funny, by “just saying whatever”. I can’t rely on the strategy of gonzo bricolage week to week, and so today I can only confess the stubborn silence of my “inner voice”, the homunculus who lives inside me and, when things are going right, dictates what I have to say. In a foundational

In a foundational  We are approaching the first anniversary of a landmark event in the art world. Although it seemed shockingly new last year, it represents the culmination of a trajectory described by Wolfe half a century ago: the de-materialization of art. On March 11th, 2021, a momentous auction was held by Christie’s. It was a dramatic departure from precedent, partly because

We are approaching the first anniversary of a landmark event in the art world. Although it seemed shockingly new last year, it represents the culmination of a trajectory described by Wolfe half a century ago: the de-materialization of art. On March 11th, 2021, a momentous auction was held by Christie’s. It was a dramatic departure from precedent, partly because  China can take the initiative in three key areas. For starters, Chinese President Xi Jinping should call for an emergency summit of G20 leaders, focused on achieving an immediate and unconditional ceasefire in this conflict and developing an agenda for a negotiated peace. The G20 is now the recognized forum for global action in the midst of crisis, having galvanized support among the world’s leading economies in

China can take the initiative in three key areas. For starters, Chinese President Xi Jinping should call for an emergency summit of G20 leaders, focused on achieving an immediate and unconditional ceasefire in this conflict and developing an agenda for a negotiated peace. The G20 is now the recognized forum for global action in the midst of crisis, having galvanized support among the world’s leading economies in