Yasmine Musa in the Hypocrite Reader:

It was the second month of lockdown and the spring stretched before me like Arabic ice cream. My dad announced that he would be out all day, so I put two tabs of acid in a water bottle and headed out to the garden. A perfect time to pretend to enjoy solitude and figure out the riddles of the universe. I pulled out a big picnic blanket, sat beneath the shade of a young apple tree and waited for the new blooms of the cactus flower to speak.

It was the second month of lockdown and the spring stretched before me like Arabic ice cream. My dad announced that he would be out all day, so I put two tabs of acid in a water bottle and headed out to the garden. A perfect time to pretend to enjoy solitude and figure out the riddles of the universe. I pulled out a big picnic blanket, sat beneath the shade of a young apple tree and waited for the new blooms of the cactus flower to speak.- Before Yusef left Berlin and went back to Beirut, he gave me Letters to a Young Poet by Rilke. In it, Rilke wrote that the solitary man must remember to see the plants and animals, “patiently and willingly uniting and increasing and growing not out of physical suffering but bowing to necessities that are greater than pleasure and pain and more powerful than will withstanding.” And that is the secret of sweetness, the young poet must realize. I read the lines over and over again that spring and did not understand what Rilke meant, which is why I took the acid.

- Bringing the acid to Palestine was Khalil’s idea. Because Khalil is my best friend from high school and I live in Berlin, it was difficult to say no. I took Khalil’s request as a divine calling and asked another friend to lead me on the path of finding a drug dealer.

More here.

Wages have been stagnant for most Americans for decades. Inequality has increased sharply. Globalization and technology have enriched some, but also fueled job losses and impoverished communities.

Wages have been stagnant for most Americans for decades. Inequality has increased sharply. Globalization and technology have enriched some, but also fueled job losses and impoverished communities.

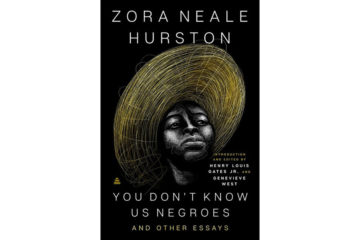

“Negro folklore is not a thing of the past,” Zora Neale Hurston wrote. “It is still in the making.”

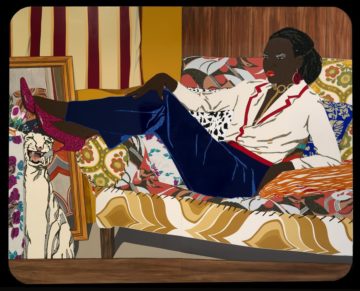

“Negro folklore is not a thing of the past,” Zora Neale Hurston wrote. “It is still in the making.” SAAM: SAAM’s website and physical spaces hold artworks and resources aplenty to take a deep dive into the presence and impact of African American artists on our world. In honor of Black History Month, here are a few of our favorite videos of artists speaking about their life, work, and inspiration.

SAAM: SAAM’s website and physical spaces hold artworks and resources aplenty to take a deep dive into the presence and impact of African American artists on our world. In honor of Black History Month, here are a few of our favorite videos of artists speaking about their life, work, and inspiration. Central banks have started reacting to inflation. In February, the Bank of England

Central banks have started reacting to inflation. In February, the Bank of England  Scientists say that urine diversion would have huge environmental and public-health benefits if deployed on a large scale around the world. That’s in part because urine is rich in nutrients that, instead of polluting water bodies, could go towards fertilizing crops or feed into industrial processes. According to Simha’s estimates, humans produce enough urine to replace about one-quarter of current nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers worldwide; it also contains potassium and many micronutrients (see ‘What’s in urine’). On top of that, not flushing urine down the drain could save vast amounts of water and reduce some of the strain on ageing and overloaded sewer systems.

Scientists say that urine diversion would have huge environmental and public-health benefits if deployed on a large scale around the world. That’s in part because urine is rich in nutrients that, instead of polluting water bodies, could go towards fertilizing crops or feed into industrial processes. According to Simha’s estimates, humans produce enough urine to replace about one-quarter of current nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers worldwide; it also contains potassium and many micronutrients (see ‘What’s in urine’). On top of that, not flushing urine down the drain could save vast amounts of water and reduce some of the strain on ageing and overloaded sewer systems. Artificial intelligence is everywhere around us. Deep-learning algorithms are used to classify images, suggest songs to us, and even to drive cars. But the quest to build truly “human” artificial intelligence is still coming up short. Gary Marcus argues that this is not an accident: the features that make neural networks so powerful also prevent them from developing a robust common-sense view of the world. He advocates combining these techniques with a more symbolic approach to constructing AI algorithms.

Artificial intelligence is everywhere around us. Deep-learning algorithms are used to classify images, suggest songs to us, and even to drive cars. But the quest to build truly “human” artificial intelligence is still coming up short. Gary Marcus argues that this is not an accident: the features that make neural networks so powerful also prevent them from developing a robust common-sense view of the world. He advocates combining these techniques with a more symbolic approach to constructing AI algorithms. A few decades ago the Stanford professor Ronald Howard

A few decades ago the Stanford professor Ronald Howard

T

T One Sunday, Malcolm X was our guest. He strode into the studio, tall, handsome, bearing his famous ironic grin. The show’s producer, the late Jimmy Lyons, suggested that the topic be Black History. This was my opening. “Of course,” I said, “Mr. X would say that Black History is distorted.” “No,” he fired back. “I’d say that it was cotton patch history.”

One Sunday, Malcolm X was our guest. He strode into the studio, tall, handsome, bearing his famous ironic grin. The show’s producer, the late Jimmy Lyons, suggested that the topic be Black History. This was my opening. “Of course,” I said, “Mr. X would say that Black History is distorted.” “No,” he fired back. “I’d say that it was cotton patch history.” Years ago, when I was still a budding fiction writer, I published an essay about how hard skateboarding is to write about. I focused on a few novelists who had skater characters in their books but who clearly didn’t skate themselves, as they got it completely wrong. But even for someone like me, who has skated for nearly 30 years, the intricacies of tricks, the goofy and convoluted terminology, and the nuanced hierarchy of difficulty all conspire to make skateboarding one of the most challenging subjects I’ve ever tackled.

Years ago, when I was still a budding fiction writer, I published an essay about how hard skateboarding is to write about. I focused on a few novelists who had skater characters in their books but who clearly didn’t skate themselves, as they got it completely wrong. But even for someone like me, who has skated for nearly 30 years, the intricacies of tricks, the goofy and convoluted terminology, and the nuanced hierarchy of difficulty all conspire to make skateboarding one of the most challenging subjects I’ve ever tackled. The

The  Misperceptions threaten to warp mass opinion and public policy on controversial issues in politics, science, and health. What explains the prevalence and persistence of these false and unsupported beliefs, which seem to be genuinely held by many people? Though limits on cognitive resources and attention play an important role, many of the most destructive misperceptions arise in domains where individuals have weak incentives to hold accurate beliefs and strong directional motivations to endorse beliefs that are consistent with a group identity such as partisanship. These tendencies are often exploited by elites who frequently create and amplify misperceptions to influence elections and public policy. Though evidence is lacking for claims of a “post-truth” era, changes in the speed with which false information travels and the extent to which it can find receptive audiences require new approaches to counter misinformation. Reducing the propagation and influence of false claims will require further efforts to inoculate people in advance of exposure (for example, media literacy), debunk false claims that are already salient or widespread (for example, fact-checking), reduce the prevalence of low-quality information (for example, changing social media algorithms), and discourage elites from promoting false information (for example, strengthening reputational sanctions).

Misperceptions threaten to warp mass opinion and public policy on controversial issues in politics, science, and health. What explains the prevalence and persistence of these false and unsupported beliefs, which seem to be genuinely held by many people? Though limits on cognitive resources and attention play an important role, many of the most destructive misperceptions arise in domains where individuals have weak incentives to hold accurate beliefs and strong directional motivations to endorse beliefs that are consistent with a group identity such as partisanship. These tendencies are often exploited by elites who frequently create and amplify misperceptions to influence elections and public policy. Though evidence is lacking for claims of a “post-truth” era, changes in the speed with which false information travels and the extent to which it can find receptive audiences require new approaches to counter misinformation. Reducing the propagation and influence of false claims will require further efforts to inoculate people in advance of exposure (for example, media literacy), debunk false claims that are already salient or widespread (for example, fact-checking), reduce the prevalence of low-quality information (for example, changing social media algorithms), and discourage elites from promoting false information (for example, strengthening reputational sanctions). In August of 2019, a special issue of the Times Magazine appeared, wearing a portentous cover—a photograph, shot by the visual artist Dannielle Bowman, of a calm sea under gray skies, the line between earth and land cleanly bisecting the frame like the stroke of a minimalist painting. On the lower half of the page was a mighty paragraph, printed in bronze letters. It began:

In August of 2019, a special issue of the Times Magazine appeared, wearing a portentous cover—a photograph, shot by the visual artist Dannielle Bowman, of a calm sea under gray skies, the line between earth and land cleanly bisecting the frame like the stroke of a minimalist painting. On the lower half of the page was a mighty paragraph, printed in bronze letters. It began: