Anne Enright at The Guardian:

When I was young, growing up in Dublin, Ulysses was considered the greatest novel in the world and the dirtiest book ever written. I bought a copy as soon as I had money and it was taken away from me when my mother discovered me reading it – though Lolita, for some reason, had passed unnoticed in our house. I was 14. I was outraged, and delighted with myself, and a little confused. Ulysses contained something worse than sex, clearly, and I did not know what that could be.

When I was young, growing up in Dublin, Ulysses was considered the greatest novel in the world and the dirtiest book ever written. I bought a copy as soon as I had money and it was taken away from me when my mother discovered me reading it – though Lolita, for some reason, had passed unnoticed in our house. I was 14. I was outraged, and delighted with myself, and a little confused. Ulysses contained something worse than sex, clearly, and I did not know what that could be.

“It is very scatological,” my mother said and then, “Look it up!” which is certainly one way to develop a daughter’s vocabulary, though the definition left me no further on. What could be so terrible – or so interesting – about going to the toilet? After much argument, I put the book up in the attic, to be taken down when I had come of age. Four years later, I retrieved it and read the thing all the way through, though I think I skipped some of the stuff in the brothel, which seemed to contain no actual information about brothels, or far too much information, none of which was real, and which managed all this at great length.

Clearly I was missing something. It was sometimes hard to tell if a character was doing a thing or only thinking about doing it and this constant sense of potential gave Joyceans a very peering look. Meanwhile, he was a very great genius, so discussions about what Joyce meant by one or another line were airy, pedantic, and so properly masculine I found it hard to join in. Reading Ulysses made a man very clever, clearly, and a woman not clever, but intriguingly dirty. For some of these intellectual types at least, there was something a little creepy in the way they said: “Fourteen?”

More here.

Y

Y Laura Kipnis in LitHub:

Laura Kipnis in LitHub: Claus Leggewie in The LA Review of Books:

Claus Leggewie in The LA Review of Books: Mariana Mazzucato in Project Syndicate:

Mariana Mazzucato in Project Syndicate: How did Constantine Cavafy get to “Ithaca”? Not the island, of course, but the 1911 poem that is Cavafy’s most famous and best-loved work, which begins by admonishing its nameless second-person addressee—who may be Homer’s Odysseus, but could also be us, the reader—to “hope that the road is a long one, / filled with adventures, filled with discoveries” as he “sets out on the way to Ithaca”: the hero’s island home, the all-important destination in the myths that Homer’s poems adapted, perhaps the most famous destination in world literature. Certainly “Ithaca” is the poet’s most famous and beloved work, at least in the anglophone world and particularly in America, where a reading of it at Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’ funeral in 1994 briefly made Cavafy a bestseller.

How did Constantine Cavafy get to “Ithaca”? Not the island, of course, but the 1911 poem that is Cavafy’s most famous and best-loved work, which begins by admonishing its nameless second-person addressee—who may be Homer’s Odysseus, but could also be us, the reader—to “hope that the road is a long one, / filled with adventures, filled with discoveries” as he “sets out on the way to Ithaca”: the hero’s island home, the all-important destination in the myths that Homer’s poems adapted, perhaps the most famous destination in world literature. Certainly “Ithaca” is the poet’s most famous and beloved work, at least in the anglophone world and particularly in America, where a reading of it at Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’ funeral in 1994 briefly made Cavafy a bestseller. In the late 1930s, British philosophy, at least at Oxford, was dominated by AJ Ayer, whose groundbreaking book Language, Truth and Logic was published in 1936. Ayer was the chief promoter of logical positivism, a school of thought that aimed to clean up philosophy by ruling out large areas of the field as unverifiable and therefore not fit for logical discussion.

In the late 1930s, British philosophy, at least at Oxford, was dominated by AJ Ayer, whose groundbreaking book Language, Truth and Logic was published in 1936. Ayer was the chief promoter of logical positivism, a school of thought that aimed to clean up philosophy by ruling out large areas of the field as unverifiable and therefore not fit for logical discussion.

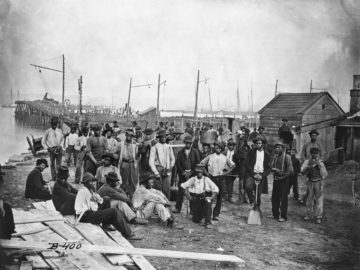

In August of 1619, the English warship White Lion sailed into Hampton Roads, Virginia, where the conjunction of the James, Elizabeth and York rivers meet the Atlantic Ocean. The White Lion’s captain and crew were privateers, and they had taken captives from a Dutch slave ship. They exchanged, for supplies, more than 20 African people with the leadership and settlers at the Jamestown colony. In 2019 this event, while not the first arrival of Africans or

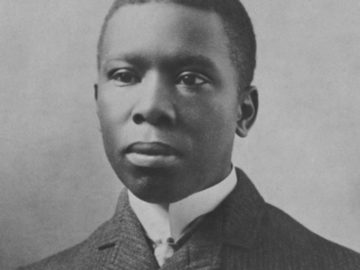

In August of 1619, the English warship White Lion sailed into Hampton Roads, Virginia, where the conjunction of the James, Elizabeth and York rivers meet the Atlantic Ocean. The White Lion’s captain and crew were privateers, and they had taken captives from a Dutch slave ship. They exchanged, for supplies, more than 20 African people with the leadership and settlers at the Jamestown colony. In 2019 this event, while not the first arrival of Africans or  “Suppose the only Negro who survived some centuries hence was the Negro painted by white Americans in the novels and essays they have written. What would people in a hundred years say of black Americans?” This is the question posed by W. E. B. Du Bois in his lecture “Criteria of Negro Art.” The remarks were made at the 1926 NAACP annual meeting in Chicago and later published as part of a multi-issue series titled “The Negro in Art” in The Crisis, the NAACP’s official magazine. Du Bois gave the speech at a ceremony honoring the contributions of the eminent author, editor, and historian Carter G. Woodson. Woodson had made it his life’s work to document the positive cultural, social, and political contributions black Americans had made to the development of the United States. He did so in an effort to combat the empty but popular rhetoric of those who suggested that black people had no history, no culture, and had nothing to add to the country beyond the labor of their bodies. That same year, Woodson developed Negro History Week, the precursor to what would eventually become Black History Month, an extension of his effort to illuminate black contributions to the American project. And while Du Bois sought to honor Woodson in his remarks, he also used the opportunity to espouse his own beliefs regarding the role and importance of black artists as America wrestled with the evolution of white supremacy only a generation after the end of slavery.

“Suppose the only Negro who survived some centuries hence was the Negro painted by white Americans in the novels and essays they have written. What would people in a hundred years say of black Americans?” This is the question posed by W. E. B. Du Bois in his lecture “Criteria of Negro Art.” The remarks were made at the 1926 NAACP annual meeting in Chicago and later published as part of a multi-issue series titled “The Negro in Art” in The Crisis, the NAACP’s official magazine. Du Bois gave the speech at a ceremony honoring the contributions of the eminent author, editor, and historian Carter G. Woodson. Woodson had made it his life’s work to document the positive cultural, social, and political contributions black Americans had made to the development of the United States. He did so in an effort to combat the empty but popular rhetoric of those who suggested that black people had no history, no culture, and had nothing to add to the country beyond the labor of their bodies. That same year, Woodson developed Negro History Week, the precursor to what would eventually become Black History Month, an extension of his effort to illuminate black contributions to the American project. And while Du Bois sought to honor Woodson in his remarks, he also used the opportunity to espouse his own beliefs regarding the role and importance of black artists as America wrestled with the evolution of white supremacy only a generation after the end of slavery. I HAVE RECENTLY REREAD

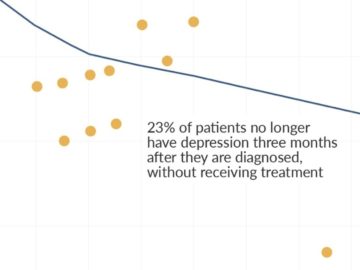

I HAVE RECENTLY REREAD In order to tackle the world’s largest problems, we need to be able to identify their causes and effective ways to solve them. How would we know about the effects of a new idea, treatment or policy? Answering this question can be difficult. Some research is poorly done and there are incentives for scientists and funders to exaggerate their findings.

In order to tackle the world’s largest problems, we need to be able to identify their causes and effective ways to solve them. How would we know about the effects of a new idea, treatment or policy? Answering this question can be difficult. Some research is poorly done and there are incentives for scientists and funders to exaggerate their findings. In The Tragedy of Macbeth, long-time Hollywood presence Joel Coen — who has 18 prior films to his credit — takes sole creative control of a project for the first time. The result, not unlike the tale of Macbeth itself, is a tragedy of epic proportions.

In The Tragedy of Macbeth, long-time Hollywood presence Joel Coen — who has 18 prior films to his credit — takes sole creative control of a project for the first time. The result, not unlike the tale of Macbeth itself, is a tragedy of epic proportions. After her death in May 1944, the painter, poet, and designer Florine Stettheimer was eulogized by fellow painter Georgia O’Keeffe. Although the two were not always on warm terms, no other female artist in the United States equaled Stettheimer for originality, sense of color, or national renown. Indeed, given that there were so few female artists in New York City—or in the United States—who made significant work during the 1920s and ’30s, O’Keeffe was both a fitting and perhaps necessary choice. However, if the orator was predictable, the speech was not. Unlike many eulogies that tend toward glossy retrospection, O’Keeffe’s remarks were purposeful and pointed. This was an opportunity to speak candidly about matters Stettheimer herself might not have expressed so directly. “Florine made no concessions of any kind to any person or situation,” O’Keeffe said. “[She] put into visible form … a way of life that is going and cannot happen again, something that has been alive in our city.”

After her death in May 1944, the painter, poet, and designer Florine Stettheimer was eulogized by fellow painter Georgia O’Keeffe. Although the two were not always on warm terms, no other female artist in the United States equaled Stettheimer for originality, sense of color, or national renown. Indeed, given that there were so few female artists in New York City—or in the United States—who made significant work during the 1920s and ’30s, O’Keeffe was both a fitting and perhaps necessary choice. However, if the orator was predictable, the speech was not. Unlike many eulogies that tend toward glossy retrospection, O’Keeffe’s remarks were purposeful and pointed. This was an opportunity to speak candidly about matters Stettheimer herself might not have expressed so directly. “Florine made no concessions of any kind to any person or situation,” O’Keeffe said. “[She] put into visible form … a way of life that is going and cannot happen again, something that has been alive in our city.” Awkwardly for today’s secular progressives, opposition to eugenics during its heyday in the West came almost exclusively from religious sources, particularly the Catholic Church. Eugenic ideas were disseminated everywhere, but few Catholic countries applied them. The only involuntary sterilisation legislation in Latin America was enacted in the state of Veracruz in Mexico in 1932. In Catholic Europe, Spain, Portugal and Italy passed no eugenic laws. By contrast, Norway and Sweden legalised eugenic sterilisation in 1934 and 1935, with Sweden requiring the consent of those sterilised only in 1976. In the US, more than 70,000 people were forcibly sterilised during the 20th century, with sterilisation without the inmates’ consent being reported in female prisons in California up to 2014.

Awkwardly for today’s secular progressives, opposition to eugenics during its heyday in the West came almost exclusively from religious sources, particularly the Catholic Church. Eugenic ideas were disseminated everywhere, but few Catholic countries applied them. The only involuntary sterilisation legislation in Latin America was enacted in the state of Veracruz in Mexico in 1932. In Catholic Europe, Spain, Portugal and Italy passed no eugenic laws. By contrast, Norway and Sweden legalised eugenic sterilisation in 1934 and 1935, with Sweden requiring the consent of those sterilised only in 1976. In the US, more than 70,000 people were forcibly sterilised during the 20th century, with sterilisation without the inmates’ consent being reported in female prisons in California up to 2014.

Salwa Sebti was growing impatient. In 2014, she and her colleagues at the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Medical Center in Dallas had begun tracking mice that had a genetically enhanced ability to detoxify their cells. The goal was to test the anti-ageing effects of boosting autophagy, the biological housekeeping process by which cells rid themselves of damaged components. But it was almost two years — a timespan roughly equivalent to 70 years in humans — before the mice showed any clear signs of health improvements.

Salwa Sebti was growing impatient. In 2014, she and her colleagues at the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Medical Center in Dallas had begun tracking mice that had a genetically enhanced ability to detoxify their cells. The goal was to test the anti-ageing effects of boosting autophagy, the biological housekeeping process by which cells rid themselves of damaged components. But it was almost two years — a timespan roughly equivalent to 70 years in humans — before the mice showed any clear signs of health improvements.