Joel Christensen in The Conversation:

Each Valentine’s Day, when I see images of the chubby winged god Cupid taking aim with his bow and arrow at his unsuspecting victims, I take refuge in my training as a scholar of early Greek poetry and myth to muse on the strangeness of this image and the nature of love.

Each Valentine’s Day, when I see images of the chubby winged god Cupid taking aim with his bow and arrow at his unsuspecting victims, I take refuge in my training as a scholar of early Greek poetry and myth to muse on the strangeness of this image and the nature of love.

In Roman culture, Cupid was the child of the goddess Venus, popularly known today as the goddess of love, and Mars, the god of war. But for ancient audiences, as myths and texts show, she was really the patron deity of “sexual intercourse” and “procreation.” The name Cupid, which comes from the Latin verb cupere, means desire, love or lust. But in the odd combination of a baby’s body with lethal weapons, along with parents associated with both love and war, Cupid is a figure of contradictions – a symbol of conflict and desire.

This history isn’t often reflected in the modern-day Valentine celebrations.

More here.

Even a mild case of COVID-19 can increase a person’s risk of cardiovascular problems for at least a year after diagnosis, a new study

Even a mild case of COVID-19 can increase a person’s risk of cardiovascular problems for at least a year after diagnosis, a new study Some time in the tense winter of 1983, when Nato forces rehearsed a nuclear endgame to the Cold War so realistic that Soviet counter-intelligence briefly suspected it to be a cover for a real attack, a Stasi officer read out a stream-of-consciousness poem to a fellow intelligence operatives inside a heavily fortified compound in East Berlin.

Some time in the tense winter of 1983, when Nato forces rehearsed a nuclear endgame to the Cold War so realistic that Soviet counter-intelligence briefly suspected it to be a cover for a real attack, a Stasi officer read out a stream-of-consciousness poem to a fellow intelligence operatives inside a heavily fortified compound in East Berlin. De Francesco’s book is a fascinating historical examination of the charlatan figure that remains valid. Drawing on a variety of historical sources, de Francesco traces this path through early modern Europe, dwelling on alchemists, worm doctors, magnetizers, prestidigitators, and mountebanks. Individuals making an appearance include long-forgotten gold-makers like Leopold Thurneißer and Marco Bragadino, purported revenants like the Count of St. Germain, self-styled healers like Doctor Eisenbarth and James Graham, magicians like Jacob Philadelphia, and occultists like the Count Alessandro di Cagliostro. De Francesco, who sometimes comes across like a phenomenological sociologist in the tradition of Walter Benjamin or Siegfried Kracauer rather than an art historian, manages to distill the traits and behaviors of all these historical figures to an archetype.

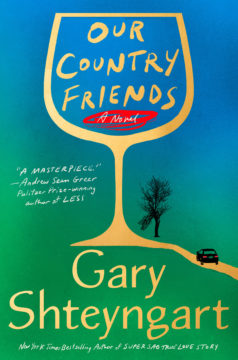

De Francesco’s book is a fascinating historical examination of the charlatan figure that remains valid. Drawing on a variety of historical sources, de Francesco traces this path through early modern Europe, dwelling on alchemists, worm doctors, magnetizers, prestidigitators, and mountebanks. Individuals making an appearance include long-forgotten gold-makers like Leopold Thurneißer and Marco Bragadino, purported revenants like the Count of St. Germain, self-styled healers like Doctor Eisenbarth and James Graham, magicians like Jacob Philadelphia, and occultists like the Count Alessandro di Cagliostro. De Francesco, who sometimes comes across like a phenomenological sociologist in the tradition of Walter Benjamin or Siegfried Kracauer rather than an art historian, manages to distill the traits and behaviors of all these historical figures to an archetype. Gary Shteyngart has quietly become one of the most talented comic writers working in English today. More or less uniquely, apart maybe from bits of Zadie Smith, he’s even funny on the subject of identity. He’s also good on both Tom Wolfe’s ‘right – BAM! – now’ and J G Ballard’s ‘next five minutes’, having trained his lens on the brutal carnival of post-Soviet Russia in Absurdistan, the impact of tech on the mating habits of youngish Americans in Super Sad True Love Story and the fallout of the financial crisis of 2008 in Lake Success. If all that were not enough, he’s an unusually acute observer of a certain strain of male sexual anguish that some of his predecessors might have treated with an indulgence bordering on mysticism, but which most of his contemporaries now seem to view as little more than an abstract social problem or a handy plot device.

Gary Shteyngart has quietly become one of the most talented comic writers working in English today. More or less uniquely, apart maybe from bits of Zadie Smith, he’s even funny on the subject of identity. He’s also good on both Tom Wolfe’s ‘right – BAM! – now’ and J G Ballard’s ‘next five minutes’, having trained his lens on the brutal carnival of post-Soviet Russia in Absurdistan, the impact of tech on the mating habits of youngish Americans in Super Sad True Love Story and the fallout of the financial crisis of 2008 in Lake Success. If all that were not enough, he’s an unusually acute observer of a certain strain of male sexual anguish that some of his predecessors might have treated with an indulgence bordering on mysticism, but which most of his contemporaries now seem to view as little more than an abstract social problem or a handy plot device.

For centuries, writers have mused on the heart as the core of humanity’s passion, its morals, its valour. The head, by contrast, was the seat of cold, hard rationality. In 1898, US poet John Godfrey Saxe wrote of such differences, but concluded his verses arguing that the heart and head are interdependent. “Each is best when both unite,” he wrote. “What were the heat without the light?” At that time, however, Saxe could not have known that the head and the heart share a deep biological connection.

For centuries, writers have mused on the heart as the core of humanity’s passion, its morals, its valour. The head, by contrast, was the seat of cold, hard rationality. In 1898, US poet John Godfrey Saxe wrote of such differences, but concluded his verses arguing that the heart and head are interdependent. “Each is best when both unite,” he wrote. “What were the heat without the light?” At that time, however, Saxe could not have known that the head and the heart share a deep biological connection. On a Wednesday morning in January,

On a Wednesday morning in January,  My friend Agnes Callard

My friend Agnes Callard  Our species owes a lot to opposable thumbs. But if evolution had given us extra thumbs, things probably wouldn’t have improved much. One thumb per hand is enough.

Our species owes a lot to opposable thumbs. But if evolution had given us extra thumbs, things probably wouldn’t have improved much. One thumb per hand is enough. Every medium of communication has its own attentional norms. Like all tacit rules that govern behavior, they get violated, but the violators typically act deliberately. For instance, the people who talk aloud in the movie theater typically aren’t ignorant of the norms; they transgress them for the lulz. Human beings are extremely skilled at recognizing and internalizing the norms of any given medium or environment.

Every medium of communication has its own attentional norms. Like all tacit rules that govern behavior, they get violated, but the violators typically act deliberately. For instance, the people who talk aloud in the movie theater typically aren’t ignorant of the norms; they transgress them for the lulz. Human beings are extremely skilled at recognizing and internalizing the norms of any given medium or environment. The Royal Geographical Society encouraged the Royal Navy to support British expeditions of Antarctica in the early 1900s. Heading from New Zealand, the expedition ship Discovery anchored off the coastline of the unknown land under the leadership of Captain Robert Falcon Scott. He chose the Anglo-Irish ex-Merchant Navy Third Officer, Ernest Shackleton, to lead the first hazardous sledge journey inland over slippery surfaces at temperatures as low as minus 62 degrees Fahrenheit. They aimed to make history by breaking the furthest South record towards the bottom of planet Earth.

The Royal Geographical Society encouraged the Royal Navy to support British expeditions of Antarctica in the early 1900s. Heading from New Zealand, the expedition ship Discovery anchored off the coastline of the unknown land under the leadership of Captain Robert Falcon Scott. He chose the Anglo-Irish ex-Merchant Navy Third Officer, Ernest Shackleton, to lead the first hazardous sledge journey inland over slippery surfaces at temperatures as low as minus 62 degrees Fahrenheit. They aimed to make history by breaking the furthest South record towards the bottom of planet Earth.

W

W Y

Y