Steven Johnson in the New York Times:

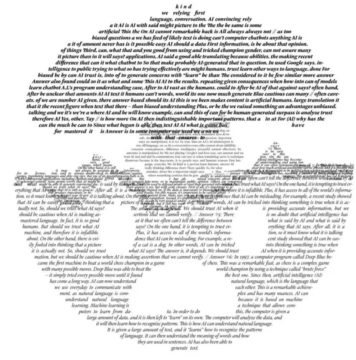

Inside one of the buildings lies a wonder of modern technology: 285,000 CPU cores yoked together into one giant supercomputer, powered by solar arrays and cooled by industrial fans. The machines never sleep: Every second of every day, they churn through innumerable calculations, using state-of-the-art techniques in machine intelligence that go by names like ‘‘stochastic gradient descent’’ and ‘‘convolutional neural networks.’’ The whole system is believed to be one of the most powerful supercomputers on the planet.

Inside one of the buildings lies a wonder of modern technology: 285,000 CPU cores yoked together into one giant supercomputer, powered by solar arrays and cooled by industrial fans. The machines never sleep: Every second of every day, they churn through innumerable calculations, using state-of-the-art techniques in machine intelligence that go by names like ‘‘stochastic gradient descent’’ and ‘‘convolutional neural networks.’’ The whole system is believed to be one of the most powerful supercomputers on the planet.

And what, you may ask, is this computational dynamo doing with all these prodigious resources? Mostly, it is playing a kind of game, over and over again, billions of times a second. And the game is called: Guess what the missing word is.

The supercomputer complex in Iowa is running a program created by OpenAI, an organization established in late 2015 by a handful of Silicon Valley luminaries, including Elon Musk; Greg Brockman, who until recently had been chief technology officer of the e-payment juggernaut Stripe; and Sam Altman, at the time the president of the start-up incubator Y Combinator. In its first few years, as it built up its programming brain trust, OpenAI’s technical achievements were mostly overshadowed by the star power of its founders. But that changed in summer 2020, when OpenAI began offering limited access to a new program called Generative Pre-Trained Transformer 3, colloquially referred to as GPT-3. Though the platform was initially available to only a small handful of developers, examples of GPT-3’s uncanny prowess with language — and at least the illusion of cognition — began to circulate across the web and through social media.

More here.

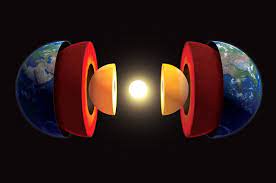

Earth’s magnetic field, nearly as old as the planet itself, protects life from damaging space radiation. But 565 million years ago, the field was sputtering, dropping to 10% of today’s strength, according to a recent discovery. Then, almost miraculously, over the course of just a few tens of millions of years, it regained its strength—just in time for the sudden profusion of complex multicellular life known as

Earth’s magnetic field, nearly as old as the planet itself, protects life from damaging space radiation. But 565 million years ago, the field was sputtering, dropping to 10% of today’s strength, according to a recent discovery. Then, almost miraculously, over the course of just a few tens of millions of years, it regained its strength—just in time for the sudden profusion of complex multicellular life known as  The basic charge against Imran Khan

The basic charge against Imran Khan  In May 2020, Omar Ruiz found himself with a broken heart. “My wife told me she was no longer in love with me,” and shortly thereafter, the couple, who had been married 11 years, separated. Not only was he crushed, he said, but as a marriage and family therapist, “this entire process challenged my professional identity,” said Mr. Ruiz, who is 36 and lives in Boston. “How could I help couples when my own marriage is falling apart?”

In May 2020, Omar Ruiz found himself with a broken heart. “My wife told me she was no longer in love with me,” and shortly thereafter, the couple, who had been married 11 years, separated. Not only was he crushed, he said, but as a marriage and family therapist, “this entire process challenged my professional identity,” said Mr. Ruiz, who is 36 and lives in Boston. “How could I help couples when my own marriage is falling apart?” “It seems as though Cromwell has More right where he wants him,” the social scientist Todd Oakley writes in his essay, “Do Pictures Stare?” Many art-loving New Yorkers will immediately get the reference. At the Frick Collection on Fifth Avenue, two portraits by the German artist Hans Holbein the Younger—one of Sir Thomas More, the other of Thomas Cromwell—faced off against each other for years from either side of a majestic fireplace in the hallowed, oak-paneled room known as the Living Hall.

“It seems as though Cromwell has More right where he wants him,” the social scientist Todd Oakley writes in his essay, “Do Pictures Stare?” Many art-loving New Yorkers will immediately get the reference. At the Frick Collection on Fifth Avenue, two portraits by the German artist Hans Holbein the Younger—one of Sir Thomas More, the other of Thomas Cromwell—faced off against each other for years from either side of a majestic fireplace in the hallowed, oak-paneled room known as the Living Hall. This story is fairly typical. Inland America is pocked with the unmarked graves of communitarian utopias—primitive socialist and communist experiments—that tried to rebuild the world on what was assumed to be virgin soil. Ephrata, Pennsylvania; Germantown, Tennessee; Utopia, Ohio; Brentwood, New York; Iowa’s Amana Colonies: these and many other towns were originally settled by communalists with lofty visions of abolishing private property, quashing material inequity, and transcending divisive individualism.

This story is fairly typical. Inland America is pocked with the unmarked graves of communitarian utopias—primitive socialist and communist experiments—that tried to rebuild the world on what was assumed to be virgin soil. Ephrata, Pennsylvania; Germantown, Tennessee; Utopia, Ohio; Brentwood, New York; Iowa’s Amana Colonies: these and many other towns were originally settled by communalists with lofty visions of abolishing private property, quashing material inequity, and transcending divisive individualism. Part of the pleasure of reading Parul Sehgal’s book reviews when she served as a critic for The New York Times was the impression that her prose had slipped past the censors. Some of her sentences had the crispness of newspaper copy but others were much more blurred and atmospheric. You could watch her trialing an idea, circling it with adjectives, letting it rise with the sound of the words.

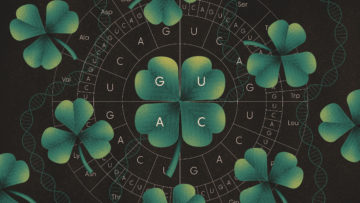

Part of the pleasure of reading Parul Sehgal’s book reviews when she served as a critic for The New York Times was the impression that her prose had slipped past the censors. Some of her sentences had the crispness of newspaper copy but others were much more blurred and atmospheric. You could watch her trialing an idea, circling it with adjectives, letting it rise with the sound of the words. As wildly diverse as life on Earth is — whether it’s a jaguar hunting down a deer in the Amazon, an orchid vine spiraling around a tree in Congo, primitive cells growing in boiling hot springs in Canada, or a stockbroker sipping coffee on Wall Street — at the genetic level, it all plays by the same rules. Four chemical letters, or nucleotide bases, spell out 64 three-letter “words” called codons, each of which stands for one of 20 amino acids. When amino acids are strung together in keeping with these encoded instructions, they form the proteins characteristic of each species. With only a few obscure exceptions, all genomes encode information identically.

As wildly diverse as life on Earth is — whether it’s a jaguar hunting down a deer in the Amazon, an orchid vine spiraling around a tree in Congo, primitive cells growing in boiling hot springs in Canada, or a stockbroker sipping coffee on Wall Street — at the genetic level, it all plays by the same rules. Four chemical letters, or nucleotide bases, spell out 64 three-letter “words” called codons, each of which stands for one of 20 amino acids. When amino acids are strung together in keeping with these encoded instructions, they form the proteins characteristic of each species. With only a few obscure exceptions, all genomes encode information identically. It’s remarkable: For more than a year, it’s been impossible to describe any world leader as a version of the sitting U.S. president. Run this thought experiment yourself: Who might be the “Joe Biden of South America”? Or “Central Europe’s Biden”? You draw a blank. What a contrast from the four years in which the world contained

It’s remarkable: For more than a year, it’s been impossible to describe any world leader as a version of the sitting U.S. president. Run this thought experiment yourself: Who might be the “Joe Biden of South America”? Or “Central Europe’s Biden”? You draw a blank. What a contrast from the four years in which the world contained  Deutsch: I am not the first to propose this idea. The Italian geologist Antonio Stoppani wrote in the 19th century that he had no hesitation in declaring man to be a new power in the universe, equivalent to the power of gravitation.

Deutsch: I am not the first to propose this idea. The Italian geologist Antonio Stoppani wrote in the 19th century that he had no hesitation in declaring man to be a new power in the universe, equivalent to the power of gravitation. Growing up, Erin Nelson used to make fun of their dad for spending so much time looking out the window at what the neighbors were up to. “Now I’m that person,” Nelson, a 31-year-old who bought their first house a year ago in Portland, Oregon, told me. “I’m always peeking out the window … That’s like my new TV.” Nelson, who uses they/them pronouns, has realized that as a homeowner, their life is bound up with the people next door in a way it never has been before.

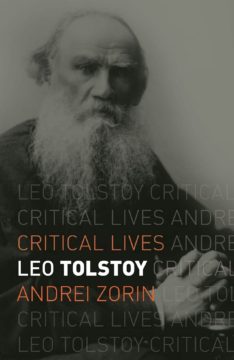

Growing up, Erin Nelson used to make fun of their dad for spending so much time looking out the window at what the neighbors were up to. “Now I’m that person,” Nelson, a 31-year-old who bought their first house a year ago in Portland, Oregon, told me. “I’m always peeking out the window … That’s like my new TV.” Nelson, who uses they/them pronouns, has realized that as a homeowner, their life is bound up with the people next door in a way it never has been before. IT IS DAUNTING to write a biography of Tolstoy. Hundreds or even thousands of books have already put each detail of his life and work under a microscope, and the archives contain no more hidden treasures. Yet, new interpretations of Tolstoy’s life continue to pour in, with more expected in the run-up to the writer’s 200th birthday in 2028. One of the most immediately obvious advantages of Andrei Zorin’s Leo Tolstoy is its brevity. And I don’t mean this as a backhanded compliment. While other biographies tend to compete with the author’s greatest novels in length, this medium-format book of roughly 200 pages will be welcomed by those who want to learn more about the legendary Russian writer without a major time commitment.

IT IS DAUNTING to write a biography of Tolstoy. Hundreds or even thousands of books have already put each detail of his life and work under a microscope, and the archives contain no more hidden treasures. Yet, new interpretations of Tolstoy’s life continue to pour in, with more expected in the run-up to the writer’s 200th birthday in 2028. One of the most immediately obvious advantages of Andrei Zorin’s Leo Tolstoy is its brevity. And I don’t mean this as a backhanded compliment. While other biographies tend to compete with the author’s greatest novels in length, this medium-format book of roughly 200 pages will be welcomed by those who want to learn more about the legendary Russian writer without a major time commitment. Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven in Aeon:

Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven in Aeon: Ajay Singh Chaudhary in Late Light:

Ajay Singh Chaudhary in Late Light: