Aimee Hinds Scott at the LARB:

FEW MONSTERS HAVE had as many revamps as Medusa. For many, our first encounter with the gorgon was the fiery stare of Ray Harryhausen’s snake-bodied stop-motion creature, as Harry Hamlin’s Perseus took her head in 1981’s Clash of the Titans. Despite becoming a cultural touchstone for representations of Medusa, Harryhausen’s creation was innovative, a far cry from ancient depictions of Perseus’ prey in presenting a predatory gorgon who attacked back. But Medusa continues to be resurrected in new and varied forms, and the contemporary pop-culture Medusa has herself moved on from her depiction in Clash of the Titans. Shucking her monstrous form, she has been the subject of considerable feminist revision. This feminist vision recasts her as a quite human victim of patriarchy and rape culture. In the most well-known ancient versions of the myth, the mortal Medusa is raped by Poseidon in Athena’s temple, resulting in her punishment by monstrous transformation. This first injustice is then compounded by Perseus’ quest for her head. Following these tales from antiquity, many of which are deeply steeped in misogyny, feminist retellings have rehabilitated the gorgon by bestowing upon her agency expressed through anger.

FEW MONSTERS HAVE had as many revamps as Medusa. For many, our first encounter with the gorgon was the fiery stare of Ray Harryhausen’s snake-bodied stop-motion creature, as Harry Hamlin’s Perseus took her head in 1981’s Clash of the Titans. Despite becoming a cultural touchstone for representations of Medusa, Harryhausen’s creation was innovative, a far cry from ancient depictions of Perseus’ prey in presenting a predatory gorgon who attacked back. But Medusa continues to be resurrected in new and varied forms, and the contemporary pop-culture Medusa has herself moved on from her depiction in Clash of the Titans. Shucking her monstrous form, she has been the subject of considerable feminist revision. This feminist vision recasts her as a quite human victim of patriarchy and rape culture. In the most well-known ancient versions of the myth, the mortal Medusa is raped by Poseidon in Athena’s temple, resulting in her punishment by monstrous transformation. This first injustice is then compounded by Perseus’ quest for her head. Following these tales from antiquity, many of which are deeply steeped in misogyny, feminist retellings have rehabilitated the gorgon by bestowing upon her agency expressed through anger.

more here.

In today’s Britain, the figure of Winston Churchill is all but deified. His face adorns the £5 note, where he glares sternly out at passersby, the only Prime Minister to be so honored; he is a perennial subject for BBC

In today’s Britain, the figure of Winston Churchill is all but deified. His face adorns the £5 note, where he glares sternly out at passersby, the only Prime Minister to be so honored; he is a perennial subject for BBC  I love writing reviews of bad books. There’s nothing like the feeling when you’re halfway through a book and it dawns on you that this book is really bad, and that it deserves a pummeling in print for misleading the reader, spreading dodgy ideas, or getting tangled up in the barbed wire of its own prose.

I love writing reviews of bad books. There’s nothing like the feeling when you’re halfway through a book and it dawns on you that this book is really bad, and that it deserves a pummeling in print for misleading the reader, spreading dodgy ideas, or getting tangled up in the barbed wire of its own prose. There are countless problems with economic sanctions.

There are countless problems with economic sanctions. Many scholars agree that a subjectively meaningful existence often

Many scholars agree that a subjectively meaningful existence often  Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis is both a Trump follower and possible Trump opponent, as he’s declined to say whether he’d face off against the former president for the 2024 GOP nomination. He’s pushed through a number of state bills that deal with hot button partisan issues, such as the recently enacted Parental Rights in Education, dubbed by critics the “don’t say gay” law, that bans school teaching of sexual topics deemed non-age-appropriate. Florida is “becoming redder all the time, and it has a very arch-conservative edge – a culture war edge,” says Orlando-based historian James Clark, author of “Hidden History of Florida.”

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis is both a Trump follower and possible Trump opponent, as he’s declined to say whether he’d face off against the former president for the 2024 GOP nomination. He’s pushed through a number of state bills that deal with hot button partisan issues, such as the recently enacted Parental Rights in Education, dubbed by critics the “don’t say gay” law, that bans school teaching of sexual topics deemed non-age-appropriate. Florida is “becoming redder all the time, and it has a very arch-conservative edge – a culture war edge,” says Orlando-based historian James Clark, author of “Hidden History of Florida.” Van Etten often counters the sonic immensity of her new album, stacked with towering choruses, moody synths, and a lingering sense of despair, with lamplit views of the hearth. On the festival-ready “Anything,” she presents an image glowing with the warmth of an Edward Hopper painting, bellowing, “You love him by the stove light in your arms.” Talking about the song’s origin story, she remembers cooking dinner one night, and as the jazz pianist Bud Powell’s “

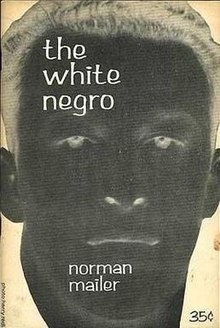

Van Etten often counters the sonic immensity of her new album, stacked with towering choruses, moody synths, and a lingering sense of despair, with lamplit views of the hearth. On the festival-ready “Anything,” she presents an image glowing with the warmth of an Edward Hopper painting, bellowing, “You love him by the stove light in your arms.” Talking about the song’s origin story, she remembers cooking dinner one night, and as the jazz pianist Bud Powell’s “ Roughly speaking, “The White Negro” contends that, in the aftermath of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, the human race as a whole now finds itself in the same psychic and physical predicament experienced by black people in America in the 1950s – that is, deindividualised, oppressed by violent systems of control, risking their lives every time they walked down the street. To live authentically in such a world, Mailer suggests, we must become “white Negroes”, or hipsters. Our morality must be psychopathic – radically free from inherited codes. Our philosophy must be existentialist. We must live like teenage hoodlums – weighing up the “therapeutic” value of “beat[ing] in the brains of a candy store keeper”.

Roughly speaking, “The White Negro” contends that, in the aftermath of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, the human race as a whole now finds itself in the same psychic and physical predicament experienced by black people in America in the 1950s – that is, deindividualised, oppressed by violent systems of control, risking their lives every time they walked down the street. To live authentically in such a world, Mailer suggests, we must become “white Negroes”, or hipsters. Our morality must be psychopathic – radically free from inherited codes. Our philosophy must be existentialist. We must live like teenage hoodlums – weighing up the “therapeutic” value of “beat[ing] in the brains of a candy store keeper”. The idea goes like this. Once upon a time, private property was unknown. Food went to those in need. Everyone was cared for. Then agriculture arose and, with it, ownership over land, labour and wild resources. The organic community splintered under the weight of competition. The story predates Marx and Engels. The patron saint of capitalism,

The idea goes like this. Once upon a time, private property was unknown. Food went to those in need. Everyone was cared for. Then agriculture arose and, with it, ownership over land, labour and wild resources. The organic community splintered under the weight of competition. The story predates Marx and Engels. The patron saint of capitalism,  “We’re doing a really terrible job of communicating risk,” said Katelyn Jetelina, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. “I think that’s also why people are throwing their hands up in the air and saying, ‘Screw it.’ They’re desperate for some sort of guidance.”

“We’re doing a really terrible job of communicating risk,” said Katelyn Jetelina, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. “I think that’s also why people are throwing their hands up in the air and saying, ‘Screw it.’ They’re desperate for some sort of guidance.” In developing a nuclear arsenal that will soon rival those of Russia and the United States, China is not merely departing from its decades-old status as a minor nuclear state; it is also upending the bipolar nuclear power system. For the 73 years since the Soviet Union’s first nuclear test, that bipolar system, for all its flaws and moments of terror, has averted nuclear war. Now, by closing in on parity with the two existing great nuclear powers, China is heralding a paradigm shift to something much less stable: a tripolar nuclear system. In that world, there will be both a greater risk of a nuclear arms race and heightened incentives for states to resort to nuclear weapons in a crisis. With three competing great nuclear powers, many of the features that enhanced stability in the bipolar system will be rendered either moot or far less reliable.

In developing a nuclear arsenal that will soon rival those of Russia and the United States, China is not merely departing from its decades-old status as a minor nuclear state; it is also upending the bipolar nuclear power system. For the 73 years since the Soviet Union’s first nuclear test, that bipolar system, for all its flaws and moments of terror, has averted nuclear war. Now, by closing in on parity with the two existing great nuclear powers, China is heralding a paradigm shift to something much less stable: a tripolar nuclear system. In that world, there will be both a greater risk of a nuclear arms race and heightened incentives for states to resort to nuclear weapons in a crisis. With three competing great nuclear powers, many of the features that enhanced stability in the bipolar system will be rendered either moot or far less reliable. How do you like to pay? Do you prefer to tap, wave, insert, single-click or double-click – or are you a hold out for hard cash? If it’s the latter, you’re fast becoming the exception. Between our growing enthusiasm for online shopping, the ease and speed with which we can now make electronic bank transfers, and the inexorable rise of cards and the advent of digital wallets, more and more of us are shunning physical money. This is still a relatively recent trend.

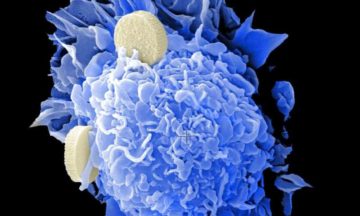

How do you like to pay? Do you prefer to tap, wave, insert, single-click or double-click – or are you a hold out for hard cash? If it’s the latter, you’re fast becoming the exception. Between our growing enthusiasm for online shopping, the ease and speed with which we can now make electronic bank transfers, and the inexorable rise of cards and the advent of digital wallets, more and more of us are shunning physical money. This is still a relatively recent trend.  Kinase inhibitors are a type of targeted

Kinase inhibitors are a type of targeted  “What is writing good for if we can’t write a way out of this darkest timeline?” (264), Karen Cheung asks in this hauntingly moving memoir of her life in Hong Kong over these last two decades. Since the passage of the National Security Law (NSL) in the summer of 2020, “Hong Kong is dead” has become a common refrain in international news. Amid constant crackdowns and arrests, Hong Kong no longer fits the image of a vibrant cosmopolitan city where foreign corporations, tourists, and expatriates can enjoy unbridled freedom. Beginning with a scathing and acute interrogation of this narrative, Cheung’s memoir cannot write Hong Kong out of its darkest timeline, but it has succeeded in lifting up the deeds and voices of Hongkongers who have always dared to imagine and work towards a better collective future for the city.

“What is writing good for if we can’t write a way out of this darkest timeline?” (264), Karen Cheung asks in this hauntingly moving memoir of her life in Hong Kong over these last two decades. Since the passage of the National Security Law (NSL) in the summer of 2020, “Hong Kong is dead” has become a common refrain in international news. Amid constant crackdowns and arrests, Hong Kong no longer fits the image of a vibrant cosmopolitan city where foreign corporations, tourists, and expatriates can enjoy unbridled freedom. Beginning with a scathing and acute interrogation of this narrative, Cheung’s memoir cannot write Hong Kong out of its darkest timeline, but it has succeeded in lifting up the deeds and voices of Hongkongers who have always dared to imagine and work towards a better collective future for the city.