Arundhati Roy’s Sissy Farenthold Lecture at the University of Texas, in Literary Hub:

Before I begin, I would like to say a few words about the war in Ukraine. I unequivocally condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and applaud the Ukrainian peoples’ courageous resistance. I applaud the courage shown by Russian dissenters at enormous cost to themselves.

Before I begin, I would like to say a few words about the war in Ukraine. I unequivocally condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and applaud the Ukrainian peoples’ courageous resistance. I applaud the courage shown by Russian dissenters at enormous cost to themselves.

I say this while being acutely and painfully aware of the hypocrisy of the United States and Europe, which together have waged similar wars on other countries in the world. Together they have led the nuclear race and have stockpiled enough weapons to destroy our planet many times over. What an irony it is that the very fact that they possess these weapons, now forces them to helplessly watch as a country they consider to be an ally is decimated—a country whose people and territory, whose very existence, imperial powers have jeopardized with their war games and ceaseless quest for domination.

And now, I turn to India. I dedicate this talk to the increasing numbers of prisoners of conscience in India.

More here.

I am an

I am an  “Ken’s fearless passion for justice, his courage and compassion towards the victims of human rights violations and atrocity crimes was not just professional responsibility but a personal conviction to him,” said Fatou Bensouda, former chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court. “He has indeed been a great inspiration to me and my colleagues.”

“Ken’s fearless passion for justice, his courage and compassion towards the victims of human rights violations and atrocity crimes was not just professional responsibility but a personal conviction to him,” said Fatou Bensouda, former chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court. “He has indeed been a great inspiration to me and my colleagues.” We see a pile of cloth in a barely lit room. We look, and we look some more, and might make out an ever-so-slight movement under the cloth, as if the object were breathing. Then wham: a walloping sound bursts the silence, the covers fall back, and Tilda Swinton rises into frame.

We see a pile of cloth in a barely lit room. We look, and we look some more, and might make out an ever-so-slight movement under the cloth, as if the object were breathing. Then wham: a walloping sound bursts the silence, the covers fall back, and Tilda Swinton rises into frame. Upon returning to Paris in the aftermath of the riots, Bourouissa began spending time in the banlieues with friends, who introduced him to more people who lived there. He eventually conscripted these figures, mostly men from immigrant backgrounds, as subjects for a series of staged photographs composed in the tradition of tableaux vivants, or living pictures—an uncanny arrangement that places ordinary people in relief against their normal environments, to an intimate yet estranging effect. The first of these staged pictures, “La fenêtre” (“The Window”), depicts two Black men captured mid-conversation, a shocking lime-green wall their background. The taut musculature of their torsos—one clothed, the other bare, a large tattoo sprawling across the curve of his back—is accentuated by the light streaming in through the titular window at top left, heightening the dramatic tension that pervades the scene. Here, the two figures stand in for the strained relations between the state and its frustrated poor, and between civil society and the immigrant class circumscribed to its périphérique—the name Bourouissa would later give to the series of photographs, after the circular highway separating Paris from its outer suburbs.

Upon returning to Paris in the aftermath of the riots, Bourouissa began spending time in the banlieues with friends, who introduced him to more people who lived there. He eventually conscripted these figures, mostly men from immigrant backgrounds, as subjects for a series of staged photographs composed in the tradition of tableaux vivants, or living pictures—an uncanny arrangement that places ordinary people in relief against their normal environments, to an intimate yet estranging effect. The first of these staged pictures, “La fenêtre” (“The Window”), depicts two Black men captured mid-conversation, a shocking lime-green wall their background. The taut musculature of their torsos—one clothed, the other bare, a large tattoo sprawling across the curve of his back—is accentuated by the light streaming in through the titular window at top left, heightening the dramatic tension that pervades the scene. Here, the two figures stand in for the strained relations between the state and its frustrated poor, and between civil society and the immigrant class circumscribed to its périphérique—the name Bourouissa would later give to the series of photographs, after the circular highway separating Paris from its outer suburbs. The company announced on Monday that it has

The company announced on Monday that it has  Modern civilization, it is said, would be impossible without measurement. And measurement would be pointless if we weren’t all using the same units. So, for nearly 150 years, the world’s metrologists have agreed on strict definitions for units of measurement through the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, known by its French acronym, B.I.P.M., and based outside Paris. Nowadays the bureau regulates the seven base units that govern time, length, mass, electrical current, temperature, the intensity of light and the amount of a substance. Together, these units are the language of science, technology and commerce.

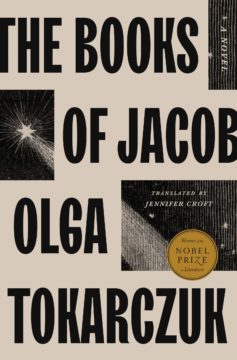

Modern civilization, it is said, would be impossible without measurement. And measurement would be pointless if we weren’t all using the same units. So, for nearly 150 years, the world’s metrologists have agreed on strict definitions for units of measurement through the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, known by its French acronym, B.I.P.M., and based outside Paris. Nowadays the bureau regulates the seven base units that govern time, length, mass, electrical current, temperature, the intensity of light and the amount of a substance. Together, these units are the language of science, technology and commerce. The Seattle Times chatted with Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk about her immersive, visionary 1,000-page novel that follows the extraordinary life of Jacob Frank, a Polish Jew who believed himself to be the Messiah and commanded a large religious movement in the 18th century.

The Seattle Times chatted with Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk about her immersive, visionary 1,000-page novel that follows the extraordinary life of Jacob Frank, a Polish Jew who believed himself to be the Messiah and commanded a large religious movement in the 18th century. On April 4,

On April 4, I think we’re laboring under a moment in which many believe that the sole function of art is to provide moral guidance.

I think we’re laboring under a moment in which many believe that the sole function of art is to provide moral guidance.

Wet earth. Loam. Bitter ash, brine on the wind. The unfurling of cedar, a smell that takes me out of this place and back to bathtubs in Japan; a portal of a scent, sacred and red. These are the smells of the Pacific Northwest wood from where I write this. In the daytime, as light pours around the unfamiliar landscape, I think of it as a new smell, something to gulp. But last night, clambering up the half-hill toward the cottage where I am staying, I took another breath and was suddenly tearful. The damp soil transformed into the smell of my Jiji, wood-smoke mimicking cigarette-smoke lingering in the folds of his shirt.

Wet earth. Loam. Bitter ash, brine on the wind. The unfurling of cedar, a smell that takes me out of this place and back to bathtubs in Japan; a portal of a scent, sacred and red. These are the smells of the Pacific Northwest wood from where I write this. In the daytime, as light pours around the unfamiliar landscape, I think of it as a new smell, something to gulp. But last night, clambering up the half-hill toward the cottage where I am staying, I took another breath and was suddenly tearful. The damp soil transformed into the smell of my Jiji, wood-smoke mimicking cigarette-smoke lingering in the folds of his shirt. “We often begin to understand things only after they break down. This is why, in addition to being a worldwide catastrophe, the pandemic has been a large-scale philosophical experiment,” Jonathan Malesic, author of The End of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives,

“We often begin to understand things only after they break down. This is why, in addition to being a worldwide catastrophe, the pandemic has been a large-scale philosophical experiment,” Jonathan Malesic, author of The End of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives,