Lee Harris in Phenomenal World:

Lee Harris in Phenomenal World:

After weeks of rising domestic pressure, a spiraling economic crisis, and the swift loss of crucial military support, Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan was removed from office last weekend following a vote of no confidence. The political turmoil is the latest in a worrisome series of events in the country—the price of food has risen sharply in recent months, along with gas and other essentials. And Pakistan’s rupee plummeted against the dollar, raising concern that higher bills for basic imports may deplete its dollar reserves.

Khan’s erratic style went from being seen as an asset—bucking pressures from Western lenders—to a liability, as the government reversed course on key policies and contributed to heightened economic instability. In a speech following his election, Khan’s successor, interim Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, said the former cricket player and socialite had run a government that was “corrupt, incompetent and laid-back.”

His dismissal comes as the war in Ukraine and rate hikes by the US Federal Reserve pose immense challenges for heavily dollar-indebted developing countries. A late January poll found that two-thirds of Pakistanis considered double-digit inflation to be the biggest problem facing the country. But tens of thousands protested across the streets of major cities on Sunday night, showing their support of Khan and echoing his unsubstantiated claim that the ouster was a result of US meddling.

More here.

R

R Instead of following the well-worn path of thinking about Abraham as the father of a nation, we are presented with a traveling herder about whom we know nothing other than that he had a beautiful wife. Calasso points out that among “the many causes of bafflement scholars come up against in the Bible one of the most glaring is the fact that there are three occasions in Genesis when a man tries to pass off his wife as his sister.” Recalling these episodes alongside the accounts of fathers willing to send out their daughters to be raped by mobs casts these men in rather unflattering light. But more importantly, it raises the question of how the books of the Bible were assembled, how and why stories were included or deleted. The “main author of the Bible,” writes Calasso, “could be thought of as the unknown Final Redactor, who thus becomes responsible for all the innumerable occasions of perplexity that the Bible is bound to provoke in anyone.” This seems to be the interpretative crux. The Bible continues to inspire our cultural and religious imaginary. The question is not whether to read it — it is how we read it.

Instead of following the well-worn path of thinking about Abraham as the father of a nation, we are presented with a traveling herder about whom we know nothing other than that he had a beautiful wife. Calasso points out that among “the many causes of bafflement scholars come up against in the Bible one of the most glaring is the fact that there are three occasions in Genesis when a man tries to pass off his wife as his sister.” Recalling these episodes alongside the accounts of fathers willing to send out their daughters to be raped by mobs casts these men in rather unflattering light. But more importantly, it raises the question of how the books of the Bible were assembled, how and why stories were included or deleted. The “main author of the Bible,” writes Calasso, “could be thought of as the unknown Final Redactor, who thus becomes responsible for all the innumerable occasions of perplexity that the Bible is bound to provoke in anyone.” This seems to be the interpretative crux. The Bible continues to inspire our cultural and religious imaginary. The question is not whether to read it — it is how we read it. Lake Mary Jane is shallow—twelve feet deep at most—but she’s well connected. She makes her home in central Florida, in an area that was once given over to wetlands. To the north, she is linked to a marsh, and to the west a canal ties her to Lake Hart. To the south, through more canals, Mary Jane feeds into a chain of lakes that run into Lake Kissimmee, which feeds into Lake Okeechobee. Were Lake Okeechobee not encircled by dikes, the water that flows through Mary Jane would keep pouring south until it glided across the Everglades and out to sea.

Lake Mary Jane is shallow—twelve feet deep at most—but she’s well connected. She makes her home in central Florida, in an area that was once given over to wetlands. To the north, she is linked to a marsh, and to the west a canal ties her to Lake Hart. To the south, through more canals, Mary Jane feeds into a chain of lakes that run into Lake Kissimmee, which feeds into Lake Okeechobee. Were Lake Okeechobee not encircled by dikes, the water that flows through Mary Jane would keep pouring south until it glided across the Everglades and out to sea. A

A Ralph Gerber* has tried nearly everything a wealthy alcoholic can try during two decades of excessive drinking: half a dozen stints in rehab, Alcoholics Anonymous, even a shaman-led quest through the Arizona desert. Each time, the treatments got him sober, yet the 48-year-old real estate broker in Los Angeles kept relapsing. His divorce, problems at his firm, the Covid lockdowns — there was always a trigger that sent him back to the gin.

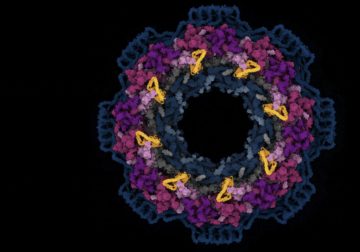

Ralph Gerber* has tried nearly everything a wealthy alcoholic can try during two decades of excessive drinking: half a dozen stints in rehab, Alcoholics Anonymous, even a shaman-led quest through the Arizona desert. Each time, the treatments got him sober, yet the 48-year-old real estate broker in Los Angeles kept relapsing. His divorce, problems at his firm, the Covid lockdowns — there was always a trigger that sent him back to the gin. For more than a decade, molecular biologist Martin Beck and his colleagues have been trying to piece together one of the world’s hardest jigsaw puzzles: a detailed model of the largest molecular machine in human cells.

For more than a decade, molecular biologist Martin Beck and his colleagues have been trying to piece together one of the world’s hardest jigsaw puzzles: a detailed model of the largest molecular machine in human cells. If one wishes to be exposed to news, information or perspective that contravenes the prevailing US/NATO view on the war in Ukraine, a rigorous search is required. And there is no guarantee that search will succeed. That is because the state/corporate censorship regime that has been imposed in the West with regard to this war is stunningly aggressive, rapid and comprehensive.

If one wishes to be exposed to news, information or perspective that contravenes the prevailing US/NATO view on the war in Ukraine, a rigorous search is required. And there is no guarantee that search will succeed. That is because the state/corporate censorship regime that has been imposed in the West with regard to this war is stunningly aggressive, rapid and comprehensive. Haven draws on a compendious knowledge of her subject, having mused on and written about Miłosz for more than 20 years. She met with the man himself on two occasions in early 2000, visits that turned out to be his last interviews in the United States, and since then she has talked with his translators, including Robert Hass, Lillian Vallee, and Peter Dale Scott; his family, including his son, Anthony, and his brother-in-law, Bill Thigpen; and his friends, including Mark Danner, who purchased Miłosz’s longtime home on Grizzly Peak. She has also edited two prior volumes on Miłosz, one collection of interviews and one of essays; has penned dozens of blog posts relating to him on her fecund

Haven draws on a compendious knowledge of her subject, having mused on and written about Miłosz for more than 20 years. She met with the man himself on two occasions in early 2000, visits that turned out to be his last interviews in the United States, and since then she has talked with his translators, including Robert Hass, Lillian Vallee, and Peter Dale Scott; his family, including his son, Anthony, and his brother-in-law, Bill Thigpen; and his friends, including Mark Danner, who purchased Miłosz’s longtime home on Grizzly Peak. She has also edited two prior volumes on Miłosz, one collection of interviews and one of essays; has penned dozens of blog posts relating to him on her fecund  In 1968, Yvonne Rainer wrote an essay criticizing “much of the western dancing we are familiar with” for the way in which, in any given “phrase,” the “focus of attention” is “the part that is the most still” and that registers “like a photograph.”

In 1968, Yvonne Rainer wrote an essay criticizing “much of the western dancing we are familiar with” for the way in which, in any given “phrase,” the “focus of attention” is “the part that is the most still” and that registers “like a photograph.” The metaverse leapt into popular awareness in 2021, in a world all too prepared for virtual sociality thanks to a year and counting of pandemic social distancing and Zoom Christmases. Last April, Epic Games announced $1 billion in investment to build “revolutionary” connected social experiences. In June, Facebook announced itself as “a metaverse company”, with 10,000 employees working on virtual reality products and experiences, and by October, it had rebranded itself as Meta, driving a flurry of commentary as people scrambled to work out what that might actually mean.

The metaverse leapt into popular awareness in 2021, in a world all too prepared for virtual sociality thanks to a year and counting of pandemic social distancing and Zoom Christmases. Last April, Epic Games announced $1 billion in investment to build “revolutionary” connected social experiences. In June, Facebook announced itself as “a metaverse company”, with 10,000 employees working on virtual reality products and experiences, and by October, it had rebranded itself as Meta, driving a flurry of commentary as people scrambled to work out what that might actually mean.

The history of economics owes many of its greatest contributions to the philosophers. Like Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx and Friedrich von Hayek, Amartya Sen, who won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1998, has a formidable reputation both as a world authority on development, welfare and famine, and as a distinguished theorist and moral philosopher. Born in Bengal in 1933, Sen’s life has been one of border-crossings – geographic and intellectual – as well as the rejection of narrow identities. He is, as he once put it:

The history of economics owes many of its greatest contributions to the philosophers. Like Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx and Friedrich von Hayek, Amartya Sen, who won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1998, has a formidable reputation both as a world authority on development, welfare and famine, and as a distinguished theorist and moral philosopher. Born in Bengal in 1933, Sen’s life has been one of border-crossings – geographic and intellectual – as well as the rejection of narrow identities. He is, as he once put it: What caught your eye the last time you looked out of your airplane window? It might have been the winglet, a now ubiquitous appendage at the end of each wing, often used by airlines to display their logo and put their branding in your travel pictures.

What caught your eye the last time you looked out of your airplane window? It might have been the winglet, a now ubiquitous appendage at the end of each wing, often used by airlines to display their logo and put their branding in your travel pictures.