Category: Recommended Reading

Wednesday, June 1, 2022

Goya: Bearing true witness

Morgan Meis in The Easel:

We have probably all seen images from Goya’s so-called Black Paintings whether we realize it or not. The image known as Saturn Devouring His Son (Goya did not title these works, the titles came from later art historians) is especially ubiquitous. The painting depicts the ancient Greek and Roman mythological story in which Saturn (Kronos in the Greek) eats his own children. You’ll remember that there was a prophecy. One of the children of Saturn would overthrow him. Saturn’s solution to this problem was to eat all the children. This worked for a time, until, inevitably, it did not. But that is another story.

We have probably all seen images from Goya’s so-called Black Paintings whether we realize it or not. The image known as Saturn Devouring His Son (Goya did not title these works, the titles came from later art historians) is especially ubiquitous. The painting depicts the ancient Greek and Roman mythological story in which Saturn (Kronos in the Greek) eats his own children. You’ll remember that there was a prophecy. One of the children of Saturn would overthrow him. Saturn’s solution to this problem was to eat all the children. This worked for a time, until, inevitably, it did not. But that is another story.

In this painting by Goya we see Saturn in all his horrifying, polyphagous glory. The scene is rendered in muddy colors: ochre, brown, black and gray. The figure of Saturn emerges from the darkness and murk, grasping the torso of his son with clenching hands. Saturn has already bitten off the head and is gnawing now on the left arm. There is a certain stringiness of bloody flesh and sinew as Saturn chews and pulls. The scene is awful. And what makes it worse is the look on Saturn’s face. He, too, looks terrified. Wide-eyed, wild-eyed, Saturn gazes directly at the viewer of the scene, as if begging us to intervene in some way, or, perhaps, simply to go away.

More here.

Science is political – and that’s a bad thing

Stuart Ritchie in his Substack newsletter:

Imagine you heard a scientist saying the following:

Imagine you heard a scientist saying the following:

I’m being paid massive consultation fees by a pharmaceutical company who want the results of my research to turn out in one specific way. And that’s a good thing. I’m proud of my conflicts of interest. I tell all my students that they should have conflicts if possible. On social media, I regularly post about how science is inevitably conflicted in one way or another, and how anyone criticising me for my conflicts is simply hopelessly naive.

I hope this would at least cause you to raise an eyebrow. And that’s because, whereas this scientist is right that conflicts of interest of some kind are probably inevitable, conflicts are a bad thing.

More here.

As the neoliberal order unravels, the international economic system must make room for cooperative forms of state-driven development

Nic Johnson and Robert Manduca in the Boston Review:

On or around 1939 debates about international political economy changed. Over the course of the Cold War, economic nationalism—the attempt to use the state to advance a country’s economic interests—was crowded out of official discourse by two competing universalisms, communism on one side and liberalism on the other. Over the last few decades, however, this opposition has been scrambled. First Marxist universalism failed; the Sino-Soviet split fractured the communist project before the USSR collapsed altogether. Then, after a brief period in the sun on the international stage, liberal universalism too began to falter in a declining arc from Iraq and the Global Financial Crisis to Donald Trump’s victory on an “America First” platform.

On or around 1939 debates about international political economy changed. Over the course of the Cold War, economic nationalism—the attempt to use the state to advance a country’s economic interests—was crowded out of official discourse by two competing universalisms, communism on one side and liberalism on the other. Over the last few decades, however, this opposition has been scrambled. First Marxist universalism failed; the Sino-Soviet split fractured the communist project before the USSR collapsed altogether. Then, after a brief period in the sun on the international stage, liberal universalism too began to falter in a declining arc from Iraq and the Global Financial Crisis to Donald Trump’s victory on an “America First” platform.

In the wake of these declensions, two political economic developments have muddied the earlier Cold War waters. In October last year the Biden administration announced that it would leave tariffs on two-thirds of Chinese exports intact. This came as a surprise for those who were hoping that Trump administration policies were pathological aberrations. Trade wars, it seems, have come to enjoy bipartisan support, in the unlikeliest of places—the ostensible headquarters of neoliberal globalization.

More here.

But how does bitcoin actually work?

Wednesday Poem

The Journey Back

Larkin’s shade surprised me. He quoted Dante:

“Daylight was going and the umber air

Soothing every creature on the earth,

Freeing them from their labors everywhere.

I alone was girding myself to face

The ordeal of my journey and my duty

And not a thing had changed, as rush-hour buses

Bore the drained and laden through the city.

I might have been a wise king setting out

Under the Christmas lights—except that

It felt more like a forewarned journey back

Into the heartland of the ordinary.

Still my old self. Ready to knock one back.

A nine-to-five man who had seen poetry.

by Seamus Heaney

from Seeing Things

Faber & Faber, 1991

Do Americans Care About Space?

John Konicki and James Pethokoukis at The New Atlantis:

For more than a half-century, America has been a world leader in space, from the space race of the 1960s to the shuttle to numerous deep space probes. But this leadership has often been reluctant — and in tension with a public that has been at best ambivalent and at worst outright opposed to endeavors to explore the universe. Many Americans have little interest in space and would prefer to spend money addressing problems down on Earth. This lack of public support may be why America hasn’t returned to the Moon since the Apollo 17 astronauts lifted off from it in 1972. And so the U.S. space program has yet to achieve its full potential. Despite their love of stories that promote visions of humanity as a space-faring species — such as Star Trek and 2001: A Space Odyssey — Americans haven’t cared enough about the cosmos to fulfill these ambitions.

For more than a half-century, America has been a world leader in space, from the space race of the 1960s to the shuttle to numerous deep space probes. But this leadership has often been reluctant — and in tension with a public that has been at best ambivalent and at worst outright opposed to endeavors to explore the universe. Many Americans have little interest in space and would prefer to spend money addressing problems down on Earth. This lack of public support may be why America hasn’t returned to the Moon since the Apollo 17 astronauts lifted off from it in 1972. And so the U.S. space program has yet to achieve its full potential. Despite their love of stories that promote visions of humanity as a space-faring species — such as Star Trek and 2001: A Space Odyssey — Americans haven’t cared enough about the cosmos to fulfill these ambitions.

However, the public space program may be on the cusp of a renaissance.

more here.

Angel Olsen Sees Your Pain

Amanda Petrusich at The New Yorker:

On a rainy afternoon in mid-April, the singer and songwriter Angel Olsen steered a Subaru through Asheville, North Carolina, while a cardboard box of VHS tapes clattered in the back seat. Olsen, who is thirty-five, had recently excavated them from her childhood home, in St. Louis. Some promised footage of significant events—“Angel’s Graduation,” “Angel’s First Day of Preschool”—and others were labelled “the pokemon” and “world premiere dark horizon.” After pulling up at a video-restoration shop, Olsen did some hasty sorting in the parking lot, trying to decide which tapes were worth dusting off with a tissue and which ones she could toss. Olsen, who was adopted when she was three years old, has spent much of the past two years figuring out what to hold on to and what to surrender. In 2021, her adoptive mother and father died two months apart (her mother, from heart failure, at age seventy-eight; her father, in his sleep, at eighty-nine), shortly after she realized and told them she was gay. Ever since, Olsen has been sifting through the material and psychological aftermath.

On a rainy afternoon in mid-April, the singer and songwriter Angel Olsen steered a Subaru through Asheville, North Carolina, while a cardboard box of VHS tapes clattered in the back seat. Olsen, who is thirty-five, had recently excavated them from her childhood home, in St. Louis. Some promised footage of significant events—“Angel’s Graduation,” “Angel’s First Day of Preschool”—and others were labelled “the pokemon” and “world premiere dark horizon.” After pulling up at a video-restoration shop, Olsen did some hasty sorting in the parking lot, trying to decide which tapes were worth dusting off with a tissue and which ones she could toss. Olsen, who was adopted when she was three years old, has spent much of the past two years figuring out what to hold on to and what to surrender. In 2021, her adoptive mother and father died two months apart (her mother, from heart failure, at age seventy-eight; her father, in his sleep, at eighty-nine), shortly after she realized and told them she was gay. Ever since, Olsen has been sifting through the material and psychological aftermath.

more here.

Angel Olsen – Big Time

Alas, King Richard: A tennis father’s complex quest for victory

Harmony Holiday in Bookforum:

RICHARD WILLIAMS DEMANDS GLORY. The pursuit of glory is revised madness, the ambition of addicts, to get so high they collapse, and are forced to repeat the ascent as if for the first time. It’s preemptive repentance disguised as innocent yearning to win. You have to need vindication to need victory so desperately. Richard Williams is looking for redemption. In a scene from a 1990s video of Richard, father of tennis champions Venus and Serena Williams, we see him genuflecting on a tennis court in Compton, California, in front of a shopping cart full of tennis balls—the ground swells with them. He’s gathering the splayed balls and placing them into red plastic milk crates with the reverence of a praise dancer. What altar is this? A shrine of crumbling adobe, chalk, felt, and plastic. What utter fixation on the unglamorous, what risk of a dedication with no yield? What we know now turns the pathos in Richard’s gesture here into dramatic irony. The menial duties of this father intent on training his daughters to be the best athletes in the world will be redeemed. He will not kneel and scour the ground for these fuzzy green chess pieces in vain.

RICHARD WILLIAMS DEMANDS GLORY. The pursuit of glory is revised madness, the ambition of addicts, to get so high they collapse, and are forced to repeat the ascent as if for the first time. It’s preemptive repentance disguised as innocent yearning to win. You have to need vindication to need victory so desperately. Richard Williams is looking for redemption. In a scene from a 1990s video of Richard, father of tennis champions Venus and Serena Williams, we see him genuflecting on a tennis court in Compton, California, in front of a shopping cart full of tennis balls—the ground swells with them. He’s gathering the splayed balls and placing them into red plastic milk crates with the reverence of a praise dancer. What altar is this? A shrine of crumbling adobe, chalk, felt, and plastic. What utter fixation on the unglamorous, what risk of a dedication with no yield? What we know now turns the pathos in Richard’s gesture here into dramatic irony. The menial duties of this father intent on training his daughters to be the best athletes in the world will be redeemed. He will not kneel and scour the ground for these fuzzy green chess pieces in vain.

Richard has a scar on his shin from where an iron nail was hammered into it by disgruntled whites in his Louisiana hometown when he was just a kid; they were disgruntled because he refused to call them “mister.” A phantom crucifixion seems to trail him. His preemptive penitence is a constant—it seeps into the texture of his presence, into the way he corrects his daughters’ stance during daily practices, his curt benevolence and pent-up rage transmuted by infinite patience.

More here.

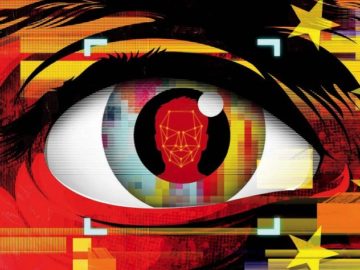

Authoritarian Regimes’ AI Innovation Advantage

Daniel Oberhaus in Harvard Magazine:

FOR THE PAST DECADE, China has led the world in advanced-facial recognition systems. Chinese companies dominate the rankings of the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Face Recognition Vendor Test, considered the accepted standard for judging the accuracy of these systems, and Chinese research papers on the subject are cited almost twice as often as American ones. Many experts recognize the importance of facial-recognition and other artificial-intelligence applications for promoting future economic growth through productivity gains, which makes understanding how China came to dominate this field a competitive concern. And after years of research, Harvard assistant professor of economics David Yang believes he’s discovered an explanation for the Chinese companies’ advantage.

FOR THE PAST DECADE, China has led the world in advanced-facial recognition systems. Chinese companies dominate the rankings of the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Face Recognition Vendor Test, considered the accepted standard for judging the accuracy of these systems, and Chinese research papers on the subject are cited almost twice as often as American ones. Many experts recognize the importance of facial-recognition and other artificial-intelligence applications for promoting future economic growth through productivity gains, which makes understanding how China came to dominate this field a competitive concern. And after years of research, Harvard assistant professor of economics David Yang believes he’s discovered an explanation for the Chinese companies’ advantage.

In a recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, Yang and his colleagues found that authoritarian states like China may have an inherent and decisive advantage over liberal democracies in facial-recognition innovation. Their secret? The flow of massive amounts of surveillance data to private AI companies that develop facial-recognition software for local police departments.

More here.

Tuesday, May 31, 2022

Google’s AI Is Smart Enough to Understand Your Humor

Imad Khan at CNET:

Jokes, sarcasm and humor require understanding the subtleties of language and human behavior. When a comedian says something sarcastic or controversial, usually the audience can discern the tone and know it’s more of an exaggeration, something that’s learned from years of human interaction.

Jokes, sarcasm and humor require understanding the subtleties of language and human behavior. When a comedian says something sarcastic or controversial, usually the audience can discern the tone and know it’s more of an exaggeration, something that’s learned from years of human interaction.

But PaLM, or Pathways Language Model, learned it without being explicitly trained on humor and the logic of jokes. After being fed two jokes, it was able to interpret them and spit out an explanation. In a blog post, Google shows how PaLM understands a novel joke not found on the internet.

More here.

Physicists Rewrite the Fundamental Law That Leads to Disorder

Philip Ball in Quanta:

In all of physical law, there’s arguably no principle more sacrosanct than the second law of thermodynamics — the notion that entropy, a measure of disorder, will always stay the same or increase. “If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell’s equations — then so much the worse for Maxwell’s equations,” wrote the British astrophysicist Arthur Eddington in his 1928 book The Nature of the Physical World. “If it is found to be contradicted by observation — well, these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation.” No violation of this law has ever been observed, nor is any expected.

In all of physical law, there’s arguably no principle more sacrosanct than the second law of thermodynamics — the notion that entropy, a measure of disorder, will always stay the same or increase. “If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell’s equations — then so much the worse for Maxwell’s equations,” wrote the British astrophysicist Arthur Eddington in his 1928 book The Nature of the Physical World. “If it is found to be contradicted by observation — well, these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation.” No violation of this law has ever been observed, nor is any expected.

But something about the second law troubles physicists. Some are not convinced that we understand it properly or that its foundations are firm. Although it’s called a law, it’s usually regarded as merely probabilistic: It stipulates that the outcome of any process will be the most probable one (which effectively means the outcome is inevitable given the numbers involved).

Yet physicists don’t just want descriptions of what will probably happen. “We like laws of physics to be exact,” said the physicist Chiara Marletto of the University of Oxford. Can the second law be tightened up into more than just a statement of likelihoods?

A number of independent groups appear to have done just that.

More here.

Economist Umair Haque chats about American Exceptionalism, climate change, and other topics

And more about this conversation by Umair Haque here.

There are ways to defeat the billionaire class and many of these tactics have been pioneered by Socialist City Councilwoman Kshama Sawant in Seattle

Chris Hedges in his Substack newsletter:

Seattle City Councilmember Kshama Sawant and the Socialist Alternative (SA) party have, for nearly a decade, waged one of the most effective battles against the city’s moneyed elites. She and the SA have adopted a series of unorthodox methods to fight the ruling oligarchs and, in that confrontation, exposed the Democratic Party leadership as craven tools of the billionaire class. Her success is one that should be closely studied and replicated in city after city if we are to dismantle corporate tyranny.

Seattle City Councilmember Kshama Sawant and the Socialist Alternative (SA) party have, for nearly a decade, waged one of the most effective battles against the city’s moneyed elites. She and the SA have adopted a series of unorthodox methods to fight the ruling oligarchs and, in that confrontation, exposed the Democratic Party leadership as craven tools of the billionaire class. Her success is one that should be closely studied and replicated in city after city if we are to dismantle corporate tyranny.

Sawant, who lives on $40,000 of her $140,000 salary and places the rest into a political fund that she uses for social justice campaigns, helped lead the fight in 2014 that made Seattle the first major American city to mandate a $15 an hour minimum wage.

More here.

The Almighty Gun

Rafia Zakaria in The Baffler:

THE CARTHAGINIANS WERE some of the richest and most powerful people in the ancient world. A Phoenician colony, Carthage was located in present-day Tunisia. The city was operative from around 800 BCE until 146 BCE, when it was sacked and destroyed by the Romans.

THE CARTHAGINIANS WERE some of the richest and most powerful people in the ancient world. A Phoenician colony, Carthage was located in present-day Tunisia. The city was operative from around 800 BCE until 146 BCE, when it was sacked and destroyed by the Romans.

There is something else that was notable about the Carthaginians. This particular ancient culture sacrificed its own children to their gods. The wealth and good fortune of their city-state, Carthaginians believed, could only be assured by pleasing the gods, and their gods were hungry for children. These children, many seemingly only a few weeks old, were taken to ritual locations known as “tophets.” The accumulation of archaeological evidence from Carthage studied in recent decades reveals that the sacrifices appeared to have been carried out year after year. Archaeologists excavating the “tophet” sites have found the cremated remains in over a thousand urns, all containing the remains of sacrificed children.

More here.

Has the ‘great resignation’ hit academia?

Virginia Gewin in Nature:

On 4 March, Christopher Jackson tweeted that he was leaving the University of Manchester, UK, to work at Jacobs, a scientific-consulting firm with headquarters in Dallas, Texas. Jackson, a prominent geoscientist, is part of a growing wave of researchers using the #leavingacademia hashtag when announcing their resignations from higher education. Like many, his discontent festered in part owing to increasing teaching demands and pressure to win grants amid lip-service-level support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

On 4 March, Christopher Jackson tweeted that he was leaving the University of Manchester, UK, to work at Jacobs, a scientific-consulting firm with headquarters in Dallas, Texas. Jackson, a prominent geoscientist, is part of a growing wave of researchers using the #leavingacademia hashtag when announcing their resignations from higher education. Like many, his discontent festered in part owing to increasing teaching demands and pressure to win grants amid lip-service-level support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

He is one of many academics who say the pandemic sparked a widespread re-evaluation of scientists’ careers and lifestyles. “Universities, spun up to full speed, expected the same and more” from struggling staff members, he says, who are now reassessing where their values lie. The demands add to long-standing discontent among early-career researchers, who must work longer and harder to successfully compete for a declining number of tenure-track or permanent posts at universities. And Jackson had another reason. He received what was, in his opinion, a racially insensitive e-mail that constituted harassment and alluded to using social media to police staff opinions, which, he says, was the last straw. Jackson filed a formal complaint and the University of Manchester responded: “The investigation has now concluded. We have made Professor Jackson aware of its findings as well as the recommendations and actions we will be taking forward as an institution.”

The level of unhappiness among academics was reflected in Nature’s 2021 annual careers survey.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

What it Was Like

If you want to know what

it was like, I’ll tell you

what my tio told me:

There was a truck driver,

Antonio, who could handle a

rig as easily in reverse as

anybody else straight ahead:

Too bad he’s a Mexican was

what my tio said the

Anglos had to say

about that.

And thus the moral:

Where do you begin if

you begin with if

you’re too good

it’s too bad?

by Leroy Quintana

from El Coro

University of Massachusetts Press, 1997

What Is Philosophy? Karl Jaspers (1949)

The Defiant Spirit Of Glasgow’s Doocots

Douglas Stuart at Lit Hub:

Doocot or dookit is the Scottish term for a dovecote or columbarium; a structure built to nest and breed domesticated pigeons. Some doo men keep their champion pigeons in doocots cut into attic spaces or adapted garden sheds, but on the schemes I lived on, we had neither attics nor gardens, and so the men who wanted to keep pigeons built their lofts out on any piece of unclaimed ground. Aesthetically they have little in common with the traditional stone dovecotes you might find on the grounds of a manor house. The doocots I remember were monolithic towers, twenty feet tall, and they were built from salvaged materials: old Formica tabletops, screwed to corrugated iron and offcuts of MDF. It gave most doocots a rickety charm, which the men tried to disguise by painting the whole thing a uniform colour.

Doocot or dookit is the Scottish term for a dovecote or columbarium; a structure built to nest and breed domesticated pigeons. Some doo men keep their champion pigeons in doocots cut into attic spaces or adapted garden sheds, but on the schemes I lived on, we had neither attics nor gardens, and so the men who wanted to keep pigeons built their lofts out on any piece of unclaimed ground. Aesthetically they have little in common with the traditional stone dovecotes you might find on the grounds of a manor house. The doocots I remember were monolithic towers, twenty feet tall, and they were built from salvaged materials: old Formica tabletops, screwed to corrugated iron and offcuts of MDF. It gave most doocots a rickety charm, which the men tried to disguise by painting the whole thing a uniform colour.

more here.