Nina Eichacker in Phenomenal World:

Nina Eichacker in Phenomenal World:

In 2022, the audience for books about John Maynard Keynes is probably as large as it has ever been. With two global economic crises followed by widespread use of government interventions, debates recently relegated to history books and academic journals have acquired new urgency. The curious reader can pick from a wealth of recent books. Geoff Mann’s In the Long Run We Are All Dead: Keynesianism, Political Economy, and Revolution (2017) and heterodox economist James Crotty’s Keynes Against Capitalism: His Economic Case for Liberal Socialism (2019) offer perspectives from critical political economy, while Zach Carter’s The Price of Peace: Money, Democracy, and the Life of John Maynard Keynes (2020) presents a detailed biography. But until now, there has been nothing quite like Stephen Marglin’s Raising Keynes, which subtly promises no less than A Twenty-first Century General Theory. The text runs to more than 896 pages, weighs four pounds in hardcover, and, as Marglin acknowledges, is not an easy read. But the result is truly original.

Marglin is uniquely positioned to carry forward the trajectory of the Keynesian tradition. Like Keynes, Marglin’s early career saw him transform from the star pupil of the reigning economic theories of his training—neoclassical economics—into a sort of a radical economist of his own category after receiving tenure. And, like Keynes, Marglin argues that it was his observation of the world around him that forced him to shed his allegiance to neoclassical theories and their claim to represent how the world works.

More here.

SAN FRANCISCO—Michael Shellenberger was more excited to tour the Tenderloin than I was, even though it was my idea. I was nervous about provoking desperate people in various states of disrepair. Shellenberger, meanwhile, seemed intent on showing that many homeless people are addicted to drugs. (If that seems callous to you, Shellenberger would say you’re in thrall to liberal “victim ideology.”) He told me not to worry. “You seem like a tough Russian chick, right?” he said as we walked up narrow sidewalks where

SAN FRANCISCO—Michael Shellenberger was more excited to tour the Tenderloin than I was, even though it was my idea. I was nervous about provoking desperate people in various states of disrepair. Shellenberger, meanwhile, seemed intent on showing that many homeless people are addicted to drugs. (If that seems callous to you, Shellenberger would say you’re in thrall to liberal “victim ideology.”) He told me not to worry. “You seem like a tough Russian chick, right?” he said as we walked up narrow sidewalks where  Ira Glass worked through and missed our scheduled Zoom interview. “It’s really just been like a normal work week, but I just didn’t manage it as ideally as I could have,” he told me, apologetically, when we chat a few days later. He missed the call because that week’s episode of This American Life, the podcast and radio show he founded in 1995 and still hosts today, had to be completely re-edited and recorded. “Stuff just has to get done… it gets very complicated.”

Ira Glass worked through and missed our scheduled Zoom interview. “It’s really just been like a normal work week, but I just didn’t manage it as ideally as I could have,” he told me, apologetically, when we chat a few days later. He missed the call because that week’s episode of This American Life, the podcast and radio show he founded in 1995 and still hosts today, had to be completely re-edited and recorded. “Stuff just has to get done… it gets very complicated.” I was reading the kinds of essays, in German, that academics write about the kinds of things that Peter is obsessed with. But my big reading event of that period was the diaries of Victor Klemperer—one of the great reading experiences of my life. It’s like if Proust were not about venal parties. It’s nonfiction, and takes place from 1933 to 1945 in Germany, from the point of view of a middle-age Jewish intellectual who survived it all out in the open, because he had a so-called Aryan wife who stood by him. He lived without having to go to a camp. And it’s so incredibly moving, because it’s a diary, so as he’s writing it, he doesn’t know what’s going to happen. There are constant bits like, Hitler’s going to get voted out. He’s going to lose the war. Everybody secretly hates him, nobody takes this guy seriously. The Americans will be here next week. It’s the most magnificent book.

I was reading the kinds of essays, in German, that academics write about the kinds of things that Peter is obsessed with. But my big reading event of that period was the diaries of Victor Klemperer—one of the great reading experiences of my life. It’s like if Proust were not about venal parties. It’s nonfiction, and takes place from 1933 to 1945 in Germany, from the point of view of a middle-age Jewish intellectual who survived it all out in the open, because he had a so-called Aryan wife who stood by him. He lived without having to go to a camp. And it’s so incredibly moving, because it’s a diary, so as he’s writing it, he doesn’t know what’s going to happen. There are constant bits like, Hitler’s going to get voted out. He’s going to lose the war. Everybody secretly hates him, nobody takes this guy seriously. The Americans will be here next week. It’s the most magnificent book. O

O W

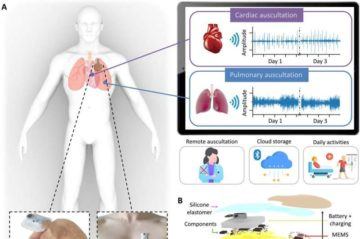

W Digital stethoscopes provide better results compared to conventional methods to record and visualize modern

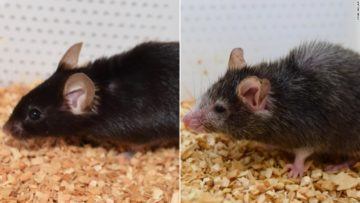

Digital stethoscopes provide better results compared to conventional methods to record and visualize modern  In molecular biologist David Sinclair’s

In molecular biologist David Sinclair’s

W

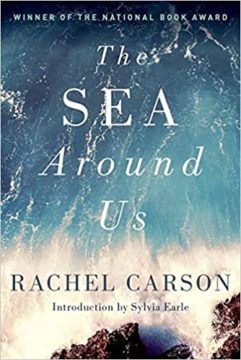

W Perhaps the most Melvillean chapter of The Sea Around Us is “Wind and Water,” which goes into fascinating detail about how winds (and volcanoes) create waves (and tsunamis), how many thousands of miles they travel, how each one is measured (five hundred miles of fetch!), and what destruction the largest of them can cause, especially when they come ashore “armed with stones and rock fragments.” Maritime history is replete with legends of gigantic waves, many of which can sound apocryphal, but Carson’s information about waves in excess of 60 feet is relentlessly persuasive. To cite only one of these, she tells of a huge wave that lifted a 135-pound rock and “hurled [it] high above the lightkeeper’s house on Tillamook Rock [in Oregon] . . . 100 feet above sea level,” smashing it to pieces. She also quotes Lord Bryce’s observation about storm surf on the coast of Tierra del Fuego, “There is not in the world a coast more terrible than this!” Charles Darwin agreed, not mincing his words: “The sight of such a coast is enough to make a landsman dream for a week about death, peril, and shipwreck.”

Perhaps the most Melvillean chapter of The Sea Around Us is “Wind and Water,” which goes into fascinating detail about how winds (and volcanoes) create waves (and tsunamis), how many thousands of miles they travel, how each one is measured (five hundred miles of fetch!), and what destruction the largest of them can cause, especially when they come ashore “armed with stones and rock fragments.” Maritime history is replete with legends of gigantic waves, many of which can sound apocryphal, but Carson’s information about waves in excess of 60 feet is relentlessly persuasive. To cite only one of these, she tells of a huge wave that lifted a 135-pound rock and “hurled [it] high above the lightkeeper’s house on Tillamook Rock [in Oregon] . . . 100 feet above sea level,” smashing it to pieces. She also quotes Lord Bryce’s observation about storm surf on the coast of Tierra del Fuego, “There is not in the world a coast more terrible than this!” Charles Darwin agreed, not mincing his words: “The sight of such a coast is enough to make a landsman dream for a week about death, peril, and shipwreck.” While it is fashionable for some female academics, journalists and social commentators to declare the

While it is fashionable for some female academics, journalists and social commentators to declare the  When the

When the This paper links two things that are often dealt with separately when discussing what we mean by the word “just” in the notion of a “just transition”. On the one hand, activists and reformers – especially those promoting the United States (US) version of the Green New Deal (GND) – see this as an opportunity to empower marginalised populations and redistribute wealth-generating assets using the state in the form of green industrial policy. On the other hand lies private finance, especially in the form of asset managers, who own huge swathes of global companies. Their investment decisions are critical to the transition, but they have no intention of allowing such a redistribution of assets and power. Indeed, they see the function of the state as using its balance sheet to insure private investors against losses. We use these competing notions of “just” as a way to discuss how we can have a transition that leverages the investments of the private sector without once again simply giving capital everything it wants at the expense of everyone else.

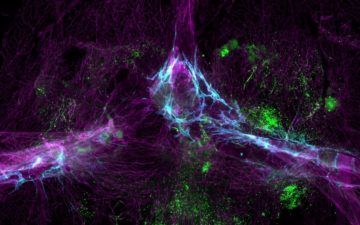

This paper links two things that are often dealt with separately when discussing what we mean by the word “just” in the notion of a “just transition”. On the one hand, activists and reformers – especially those promoting the United States (US) version of the Green New Deal (GND) – see this as an opportunity to empower marginalised populations and redistribute wealth-generating assets using the state in the form of green industrial policy. On the other hand lies private finance, especially in the form of asset managers, who own huge swathes of global companies. Their investment decisions are critical to the transition, but they have no intention of allowing such a redistribution of assets and power. Indeed, they see the function of the state as using its balance sheet to insure private investors against losses. We use these competing notions of “just” as a way to discuss how we can have a transition that leverages the investments of the private sector without once again simply giving capital everything it wants at the expense of everyone else. The brain is the body’s sovereign, and receives protection in keeping with its high status. Its cells are long-lived and shelter inside a fearsome fortification called the blood–brain barrier. For a long time, scientists thought that the brain was completely cut off from the chaos of the rest of the body — especially its eager defence system, a mass of immune cells that battle infections and whose actions could threaten a ruler caught in the crossfire. In the past decade, however, scientists have discovered that the job of protecting the brain isn’t as straightforward as they thought. They’ve learnt that its fortifications have gateways and gaps, and that its borders are bustling with active immune cells.

The brain is the body’s sovereign, and receives protection in keeping with its high status. Its cells are long-lived and shelter inside a fearsome fortification called the blood–brain barrier. For a long time, scientists thought that the brain was completely cut off from the chaos of the rest of the body — especially its eager defence system, a mass of immune cells that battle infections and whose actions could threaten a ruler caught in the crossfire. In the past decade, however, scientists have discovered that the job of protecting the brain isn’t as straightforward as they thought. They’ve learnt that its fortifications have gateways and gaps, and that its borders are bustling with active immune cells.