Timothy Brennan in the Chronicle of Higher Education:

In 1990, at the Humanities Research Institute at University of California at Irvine, I found myself sitting next to Jacques Derrida at a lecture given by Ernesto Laclau. The topic was Antonio Gramsci. At the end of the talk, of which I understood frustratingly little, Derrida asked a question that took about 20 minutes to formulate. Laclau’s response was of equal length. This mattered, because the event was the only one open to the public (it was to be followed by an invitation-only seminar). Graduate students and professors packed the lecture hall and, like Laclau himself, deferentially hung on Derrida’s every word. But they never had time to speak. The episode struck me as symbolic of the reverence deconstruction commanded at the height of its influence — and also of the hierarchies, buoyed by awestruck puzzlement, upon which it rested.

In 1990, at the Humanities Research Institute at University of California at Irvine, I found myself sitting next to Jacques Derrida at a lecture given by Ernesto Laclau. The topic was Antonio Gramsci. At the end of the talk, of which I understood frustratingly little, Derrida asked a question that took about 20 minutes to formulate. Laclau’s response was of equal length. This mattered, because the event was the only one open to the public (it was to be followed by an invitation-only seminar). Graduate students and professors packed the lecture hall and, like Laclau himself, deferentially hung on Derrida’s every word. But they never had time to speak. The episode struck me as symbolic of the reverence deconstruction commanded at the height of its influence — and also of the hierarchies, buoyed by awestruck puzzlement, upon which it rested.

At a private reception the next day, I approached Derrida to press him on his comments, for his intervention at Laclau’s lecture had, as far as I could tell, nothing to do with Gramsci. As I cited studies and quoted passages to support my point, Derrida looked up at me with quizzical eyes and a faint, perhaps condescending, smile. I was aware that my questions violated academic politesse, since to press the philosopher on issues about which he seemed ill-informed was impertinent. The underlying “joke” (which I also got, although I pretended not to) meant knowing that what Gramsci actually wrote, or why, hardly mattered — at least here.

Now, 30 years down the road, it is surprisingly hard to remember why Derrida’s “deconstruction” — a theory of reading with the unlikely catchphrase “the metaphysics of presence” — swept all before it in English departments of the American heartland, prompted Newsweek to warn of its dramatic and destructive power, and moved prominent scholars like Ruth Marcus to denounce its “semi-intelligible attacks” on reason and truth.

More here.

People mainly notice the Moon looking bigger and closer when it is full and near the horizon. This is because your mind judges how big or small an object like the Moon is

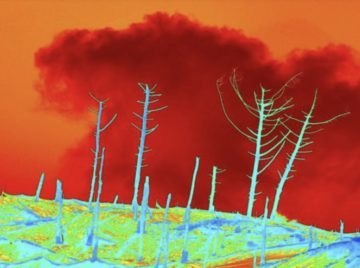

People mainly notice the Moon looking bigger and closer when it is full and near the horizon. This is because your mind judges how big or small an object like the Moon is  Ever since the notion of the “Anthropocene” was proposed by two scientists, Nobel Prize-winning chemist Paul Crutzen and marine scientist Eugene Stoermer, in a newsletter article published in 2000 by the International Council for Science, this label for the current geological epoch has led two distinct but related lives. Considered the successor to the Holocene Epoch, the Anthropocene is characterized by human harm to the earth system, including global warming and ocean acidification, the dissemination of synthetic chemicals, the redistribution of life forms across the planet, and a prospective sixth mass extinction event. In one life, the Anthropocene has been a lightning rod for questions of political economy and power. In its other, it has served as a useful scientific heuristic, assimilating mountains of measurements and calculations.

Ever since the notion of the “Anthropocene” was proposed by two scientists, Nobel Prize-winning chemist Paul Crutzen and marine scientist Eugene Stoermer, in a newsletter article published in 2000 by the International Council for Science, this label for the current geological epoch has led two distinct but related lives. Considered the successor to the Holocene Epoch, the Anthropocene is characterized by human harm to the earth system, including global warming and ocean acidification, the dissemination of synthetic chemicals, the redistribution of life forms across the planet, and a prospective sixth mass extinction event. In one life, the Anthropocene has been a lightning rod for questions of political economy and power. In its other, it has served as a useful scientific heuristic, assimilating mountains of measurements and calculations. Americans love to look on the bright side. We process our traumas and congratulate ourselves on our resilience. We like to crown ourselves winners, avoiding the stigma of the L-word deployed by a certain ex-president. The triumph of the therapeutic, as Philip Rieff called it, even applies to our anti-free-speech college students, who gain vituperative strength from the harm supposedly inflicted on them by other people’s disagreeable opinions.

Americans love to look on the bright side. We process our traumas and congratulate ourselves on our resilience. We like to crown ourselves winners, avoiding the stigma of the L-word deployed by a certain ex-president. The triumph of the therapeutic, as Philip Rieff called it, even applies to our anti-free-speech college students, who gain vituperative strength from the harm supposedly inflicted on them by other people’s disagreeable opinions. Financial literacy — the ability to understand how money works in your life — is considered the secret to taking control of your finances. Knowledge is power, as the saying goes, but information alone doesn’t lead to transformation. In putting financial literacy above all else, many in the personal finance industry have decided that repeating the same facts about how much money folks should have in their emergency savings account will, somehow, change people’s money habits. This approach doesn’t account for our human side: the parts of us that crave connection, new experiences, and fitting in as members of our communities. Most of our decisions around money are emotional; no amount of nitty-gritty knowledge about interest rates will change that.

Financial literacy — the ability to understand how money works in your life — is considered the secret to taking control of your finances. Knowledge is power, as the saying goes, but information alone doesn’t lead to transformation. In putting financial literacy above all else, many in the personal finance industry have decided that repeating the same facts about how much money folks should have in their emergency savings account will, somehow, change people’s money habits. This approach doesn’t account for our human side: the parts of us that crave connection, new experiences, and fitting in as members of our communities. Most of our decisions around money are emotional; no amount of nitty-gritty knowledge about interest rates will change that. Let’s consider where AI poetry is in 2022. Long after Racter’s 1984 debut, there are now scores of websites that use Natural Language Processing to turn words and phrases into poems with a single click of a button. There is even a tool that takes random images and creates haikus around them. You can upload an image of – say, a tree – and the tool will create a simple haiku based around it.

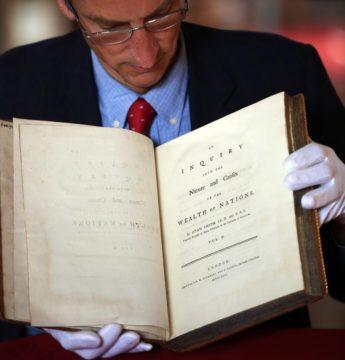

Let’s consider where AI poetry is in 2022. Long after Racter’s 1984 debut, there are now scores of websites that use Natural Language Processing to turn words and phrases into poems with a single click of a button. There is even a tool that takes random images and creates haikus around them. You can upload an image of – say, a tree – and the tool will create a simple haiku based around it. The only way to understand the “public sphere” today is by doing some historical reconstruction. Because what we’re really talking about with the history of literary criticism is an enormous shift between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries away from a media world at the center of which were the genres of periodical publication. The critics who wrote in that media sphere wrote about literature, but they were not professionalized in the way academics in the twentieth century became. This meant that they could write about pretty much anything, and they did. They won their audiences by the quality and force of their writing rather than by virtue of professional credentials. At the same time, these periodicals also published works of literature, serialized novels and other forms of literary writing, so people got a lot of exposure to literature through these periodicals, which had very large audiences. The connection between literature and public-sphere criticism was very close.

The only way to understand the “public sphere” today is by doing some historical reconstruction. Because what we’re really talking about with the history of literary criticism is an enormous shift between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries away from a media world at the center of which were the genres of periodical publication. The critics who wrote in that media sphere wrote about literature, but they were not professionalized in the way academics in the twentieth century became. This meant that they could write about pretty much anything, and they did. They won their audiences by the quality and force of their writing rather than by virtue of professional credentials. At the same time, these periodicals also published works of literature, serialized novels and other forms of literary writing, so people got a lot of exposure to literature through these periodicals, which had very large audiences. The connection between literature and public-sphere criticism was very close. Thomas O’Dwyer,

Thomas O’Dwyer, A few years ago, my book Small Wrongs was published. It has been

A few years ago, my book Small Wrongs was published. It has been  R

R Fish don’t realize they’re swimming in water.

Fish don’t realize they’re swimming in water. There’s only one word for it: indescribable. “It’s one of those awesome experiences you can’t put into words,” says fish ecologist Simon Thorrold. Thorrold is trying to explain how it feels to dive into the ocean and attach a tag to a whale shark — the most stupendous fish in the sea. “Every single time I do it, I get this huge adrenaline rush,” he says. “That’s partly about the science and the mad race to get the tags fixed. But part of it is just being human and amazed by nature and huge animals.”

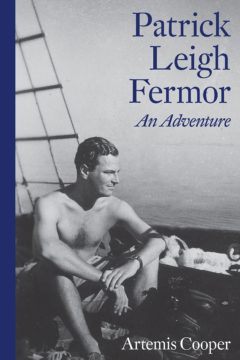

There’s only one word for it: indescribable. “It’s one of those awesome experiences you can’t put into words,” says fish ecologist Simon Thorrold. Thorrold is trying to explain how it feels to dive into the ocean and attach a tag to a whale shark — the most stupendous fish in the sea. “Every single time I do it, I get this huge adrenaline rush,” he says. “That’s partly about the science and the mad race to get the tags fixed. But part of it is just being human and amazed by nature and huge animals.” Rather than repel or frighten him as it might a conventional English gentleman travel-writer, this “atmosphere of entire strangeness” calls to Fermor, pulling him into the fray. Not only does he foray into the local market before even reaching his hotel, but soon afterward he investigates all things Créole—the language, the population, and the dress. Within a mere two days—and despite the fact that Guadeloupe ends up his least inspiring destination—he has so thoroughly immersed himself in the very things whose strangeness had captured his attention that he can bandy Créole patois terms with ease and has decoded the amorous messages indicated by the number of spikes into which the older women tie their silk Madras turbans. What is striking is the thoroughness of his inquiry and his capacity to explain the exotic without eviscerating its alluring quality of otherness.

Rather than repel or frighten him as it might a conventional English gentleman travel-writer, this “atmosphere of entire strangeness” calls to Fermor, pulling him into the fray. Not only does he foray into the local market before even reaching his hotel, but soon afterward he investigates all things Créole—the language, the population, and the dress. Within a mere two days—and despite the fact that Guadeloupe ends up his least inspiring destination—he has so thoroughly immersed himself in the very things whose strangeness had captured his attention that he can bandy Créole patois terms with ease and has decoded the amorous messages indicated by the number of spikes into which the older women tie their silk Madras turbans. What is striking is the thoroughness of his inquiry and his capacity to explain the exotic without eviscerating its alluring quality of otherness. In the spring, just before the launch of Fatherly, a Clemson University student’s

In the spring, just before the launch of Fatherly, a Clemson University student’s