Adrian Searle at The Guardian:

Among the most enigmatic works of his turbulent life, they now occupy a single room at Madrid’s Prado museum, whose collection they entered in 1881. Why Goya painted them, and even if they were all originally painted by the artist himself; how much he revised and changed them, and how much they were further altered by early restorers – all that remains a matter of debate. There is also conjecture about his house (which got its name not from Goya, but from the previous occupant), which was demolished in 1909.

Among the most enigmatic works of his turbulent life, they now occupy a single room at Madrid’s Prado museum, whose collection they entered in 1881. Why Goya painted them, and even if they were all originally painted by the artist himself; how much he revised and changed them, and how much they were further altered by early restorers – all that remains a matter of debate. There is also conjecture about his house (which got its name not from Goya, but from the previous occupant), which was demolished in 1909.

A few steps away from the Black Paintings takes us 200 years into the future, to a room of similar proportions, temporarily converted into a small cinema by the French artist Philippe Parreno, where he is showing La Quinto del Sordo, a film first seen at a Goya exhibition in Switzerland last year. Now it is paired with the paintings that provide its subject. Typically of this complex artist, there is more to it. Several times a day, the lights go down and a cellist takes a seat beside the screen, reading a statement by Spanish composer Juan Manuel Artero before beginning to play.

more here (thanks Brooks).

Cornel West is one of the most unique philosophical voices in America. He has written a ton of books and taught for over 40 years at schools like Princeton, Harvard, and now at the Union Theological Seminary.

Cornel West is one of the most unique philosophical voices in America. He has written a ton of books and taught for over 40 years at schools like Princeton, Harvard, and now at the Union Theological Seminary.

The horrifying photograph of children fleeing a deadly napalm attack has become a defining image not only of the Vietnam War but the 20th century. Dark smoke billowing behind them, the young subjects’ faces are painted with a mixture of terror, pain and confusion. Soldiers from the South Vietnamese army’s 25th Division follow helplessly behind.

The horrifying photograph of children fleeing a deadly napalm attack has become a defining image not only of the Vietnam War but the 20th century. Dark smoke billowing behind them, the young subjects’ faces are painted with a mixture of terror, pain and confusion. Soldiers from the South Vietnamese army’s 25th Division follow helplessly behind. Sascha Roth remembers the phone call came on a hectic Friday evening. She was racing around her home in Washington, D.C., to pack for New York, where she was scheduled to undergo weeks of radiation therapy for

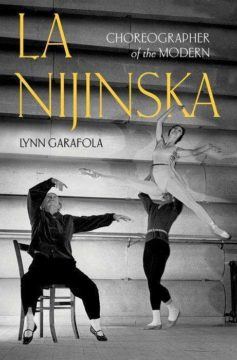

Sascha Roth remembers the phone call came on a hectic Friday evening. She was racing around her home in Washington, D.C., to pack for New York, where she was scheduled to undergo weeks of radiation therapy for  Bronislava Nijinska looked a lot like her brother, the famous dancer Vaslav Nijinsky. This proved an advantage to her own career, and a disadvantage. They’d grown up together, studied at the Imperial Ballet school in St. Petersburg, and begun their performing careers in the Maryinsky Theater. Both were trained in the virtuosic skills of the time. Acclaimed as a prodigy from the first, Vaslav left the home company soon after graduation to join Serge Diaghilev, founder of what became the legendary Ballets Russes. Vaslav’s story—his relationship with Diaghilev, his meteoric stardom in the early ballets of Michel Fokine, his budding choreographic career fostered by the possessive Diaghilev, his expulsion from the company following his marriage to Romola de Pulzsky, and his long mental deterioration—has been told many times. It’s only a sideline in Lynn Garafola’s new book La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern.

Bronislava Nijinska looked a lot like her brother, the famous dancer Vaslav Nijinsky. This proved an advantage to her own career, and a disadvantage. They’d grown up together, studied at the Imperial Ballet school in St. Petersburg, and begun their performing careers in the Maryinsky Theater. Both were trained in the virtuosic skills of the time. Acclaimed as a prodigy from the first, Vaslav left the home company soon after graduation to join Serge Diaghilev, founder of what became the legendary Ballets Russes. Vaslav’s story—his relationship with Diaghilev, his meteoric stardom in the early ballets of Michel Fokine, his budding choreographic career fostered by the possessive Diaghilev, his expulsion from the company following his marriage to Romola de Pulzsky, and his long mental deterioration—has been told many times. It’s only a sideline in Lynn Garafola’s new book La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern. Wispy, thick, swirled and streaking, the dark lines burst outward, racing or splintering. The strongest impression one is left with while paging through this exquisitely produced volume of Kafka’s complete drawings is of minimally delineated figures in states of maximally dramatised unrest.

Wispy, thick, swirled and streaking, the dark lines burst outward, racing or splintering. The strongest impression one is left with while paging through this exquisitely produced volume of Kafka’s complete drawings is of minimally delineated figures in states of maximally dramatised unrest. Living as I do, mostly by choice, in a post-Babel cacophony of languages, I find I often discern meanings that are not really there. This is particularly easy to do in the contact zones of the former Angevin Empire, where more than a millennium’s worth of cross-hybridity between English and French has brought it about that this empire’s ruins are populated principally by faux amis, so that one must not so much learn new words, as reconceive words one already knows. Thus deception becomes disappointment, to assist is not to help but only to be present, to report is to postpone, to defend is to prohibit (sometimes), to verbalise is to fine, to sense is to smell, to mount is to get in, to descend is to get out, a location is a rental, ice-cream has a perfume instead of a flavor, and so on.

Living as I do, mostly by choice, in a post-Babel cacophony of languages, I find I often discern meanings that are not really there. This is particularly easy to do in the contact zones of the former Angevin Empire, where more than a millennium’s worth of cross-hybridity between English and French has brought it about that this empire’s ruins are populated principally by faux amis, so that one must not so much learn new words, as reconceive words one already knows. Thus deception becomes disappointment, to assist is not to help but only to be present, to report is to postpone, to defend is to prohibit (sometimes), to verbalise is to fine, to sense is to smell, to mount is to get in, to descend is to get out, a location is a rental, ice-cream has a perfume instead of a flavor, and so on. Every now and then engineers make an advance, and scientists and lay people begin to ponder the question of whether that advance might yield important insight into the human mind. Descartes wondered whether the mind might work on hydraulic principles; throughout the second half of the 20th century, many wondered whether the digital computer would offer a

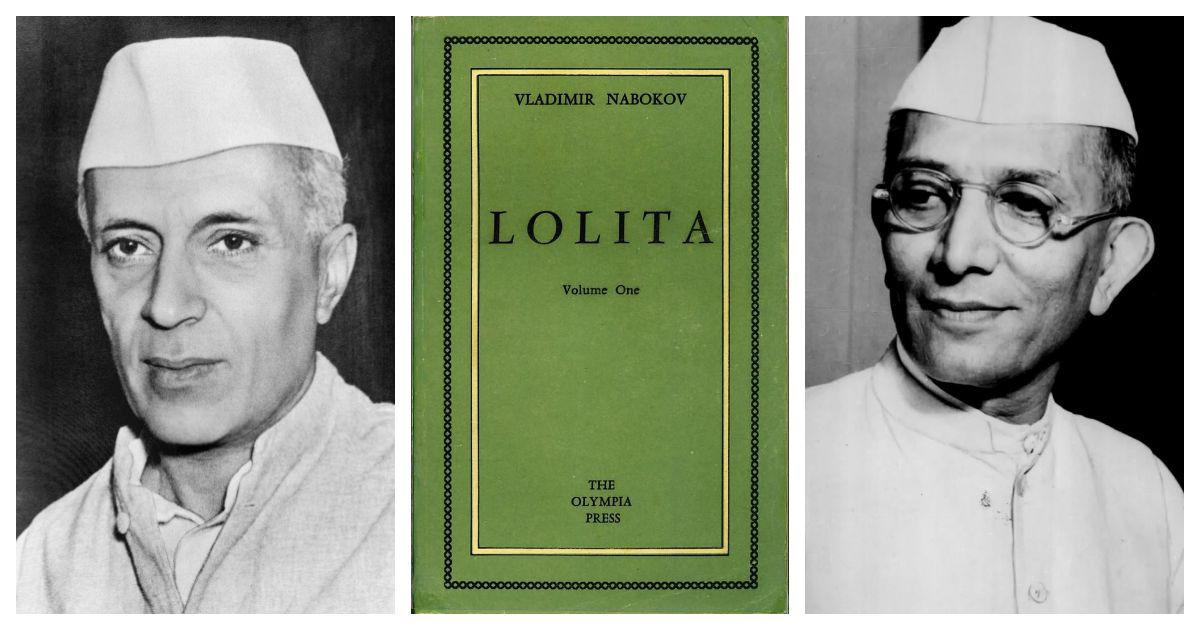

Every now and then engineers make an advance, and scientists and lay people begin to ponder the question of whether that advance might yield important insight into the human mind. Descartes wondered whether the mind might work on hydraulic principles; throughout the second half of the 20th century, many wondered whether the digital computer would offer a  In May 1959, DF Karaka, the founder editor of The Current, wrote a letter to then Finance Minister Moraji Desai about a book. Karaka explained that the book glorified a sexual relationship between a grown man and a teenage girl. He included a clipping from The Current that demanded an immediate ban on the “obscene” book.

In May 1959, DF Karaka, the founder editor of The Current, wrote a letter to then Finance Minister Moraji Desai about a book. Karaka explained that the book glorified a sexual relationship between a grown man and a teenage girl. He included a clipping from The Current that demanded an immediate ban on the “obscene” book. There’s always something relevant in clichés. If you think about it, every literary genre is a collection of clichés and commonplaces. It’s a system of expectations. The way events unfold in a fairy tale would be unacceptable in a noir novel or a science fiction story. Causal links are, to a great extent, predictable in each one of these genres. They are supposed to be predictable—even in their surprises. This is how we come to accept the reality of these worlds. And it’s so much fun to subvert those assumptions and clichés rather than to simply dismiss them, writing with one’s back turned to tradition. I should also say that these conventions usually have a heavy political load. Whenever something has calcified into a commonplace—as is the case with New York around the years of the boom and the crash—I think there is fascinating work to be done. Additionally, when I looked at the fossilized narratives from that period, I was surprised to find a void at their center: money. Even though, for obvious reasons, money is at the core of the American literature from that period, it remains a taboo—largely unquestioned and unexplored. I was unable to find many novels that talked about wealth and power in ways that were interesting to me. Class? Sure. Exploitation? Absolutely. Money? Not so much. And how bizarre is it that even though money has an almost transcendental quality in our culture it remains comparatively invisible in our literature?

There’s always something relevant in clichés. If you think about it, every literary genre is a collection of clichés and commonplaces. It’s a system of expectations. The way events unfold in a fairy tale would be unacceptable in a noir novel or a science fiction story. Causal links are, to a great extent, predictable in each one of these genres. They are supposed to be predictable—even in their surprises. This is how we come to accept the reality of these worlds. And it’s so much fun to subvert those assumptions and clichés rather than to simply dismiss them, writing with one’s back turned to tradition. I should also say that these conventions usually have a heavy political load. Whenever something has calcified into a commonplace—as is the case with New York around the years of the boom and the crash—I think there is fascinating work to be done. Additionally, when I looked at the fossilized narratives from that period, I was surprised to find a void at their center: money. Even though, for obvious reasons, money is at the core of the American literature from that period, it remains a taboo—largely unquestioned and unexplored. I was unable to find many novels that talked about wealth and power in ways that were interesting to me. Class? Sure. Exploitation? Absolutely. Money? Not so much. And how bizarre is it that even though money has an almost transcendental quality in our culture it remains comparatively invisible in our literature? In the parking areas, the drivers nestle their trucks in tightly packed rows. Their cabs function as kitchens, bedrooms, living rooms and offices. At night, drivers can be seen through their windshields — eating dinner or reclining in their bunks, bathed in the light of a Nintendo Switch or FaceTime call home.

In the parking areas, the drivers nestle their trucks in tightly packed rows. Their cabs function as kitchens, bedrooms, living rooms and offices. At night, drivers can be seen through their windshields — eating dinner or reclining in their bunks, bathed in the light of a Nintendo Switch or FaceTime call home. In March, Guy Reffitt, a supporter of the far-right militia group the Texas Three Percenters, became the first person convicted at trial for playing a role in the January 6, 2021,

In March, Guy Reffitt, a supporter of the far-right militia group the Texas Three Percenters, became the first person convicted at trial for playing a role in the January 6, 2021,  Francis Fukuyama is easily one of the most influential political thinkers of the last several decades.

Francis Fukuyama is easily one of the most influential political thinkers of the last several decades.