Max Boot in The Washington Post:

I admit to having been skeptical, ahead of time, of the hearings planned by the House select committee investigating the events of Jan. 6, 2021. What more is there to be said, I wondered? The evidence of Donald Trump’s guilt in inciting an insurrection was already so obvious that it was hard to imagine that the committee would have much to add. This was not, after all, a situation such as Watergate, where the scandal happened behind closed doors. The entire nation saw Trump’s incendiary remarks and tweets, and the riot that followed, on national television.

I admit to having been skeptical, ahead of time, of the hearings planned by the House select committee investigating the events of Jan. 6, 2021. What more is there to be said, I wondered? The evidence of Donald Trump’s guilt in inciting an insurrection was already so obvious that it was hard to imagine that the committee would have much to add. This was not, after all, a situation such as Watergate, where the scandal happened behind closed doors. The entire nation saw Trump’s incendiary remarks and tweets, and the riot that followed, on national television.

I am happy to say I was wrong. The committee’s hearings are exceeding expectations, because it is not behaving like a typical congressional committee. There is no grandstanding and no preening. There are no petty partisan squabbles. There is not even the disjointedness that normally occurs when a bunch of politicians are each given five minutes to question each witness. There is only the relentless march of evidence, all of it deeply incriminating to a certain former president who keeps insisting that he was robbed of his rightful election victory.

The committee’s recent hearings — there have been two in the past week, with more planned — have been organized like carefully choreographed television productions, and I mean that as a compliment. The committee has been focused on doing what all good television productions, whether factual or fictional, do: telling a story that enthralls the viewer.

More here.

When the Restoration ended his career in Britain’s Commonwealth government in 1660, John Milton turned his full attention to the verse tragedy he’d started around 1640, then called “Adam Unparadised.” By now in his 50s, blind and ailing, Milton composed “Paradise Lost” aloud, in bed or (per witnesses) “leaning backward obliquely in an easy chair, with his leg flung over the elbow of it,” memorizing the stanzas to be transcribed in another’s hand.

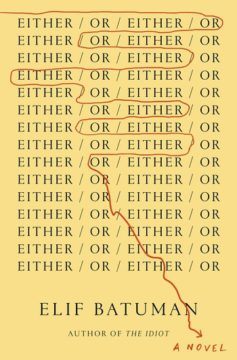

When the Restoration ended his career in Britain’s Commonwealth government in 1660, John Milton turned his full attention to the verse tragedy he’d started around 1640, then called “Adam Unparadised.” By now in his 50s, blind and ailing, Milton composed “Paradise Lost” aloud, in bed or (per witnesses) “leaning backward obliquely in an easy chair, with his leg flung over the elbow of it,” memorizing the stanzas to be transcribed in another’s hand. EARLY IN ELIF BATUMAN’S NEW NOVEL Either/Or, she quotes a blurb on the front of Kazuo Ishiguro’s An Artist of the Floating World, extracted from its 1986 review in the New York Times. “Good writers abound—good novelists are very rare,” the critic theorizes, deeming Ishiguro “not only a good writer, but also a wonderful novelist.” For Either/Or’s narrator, the distinction comes as a shock. Since she was young, Selin has aspired to become a novelist, and she views much of her life to date as training for that vocation. Assessing herself according to the reviewer’s implied rubric, Selin realizes that her facility with language, her sparkling insights and clever turns of phrase, may not be sufficient. “It was what I had been counting on,” she thinks. “My sense of being a good writer. My stomach sank with the knowledge of how wrong I had been.” This is in some sense the anxiety that haunts Either/Or: Batuman is demonstrably, incontrovertibly a good writer—but is she a good novelist? (And what is a good novel anyway?)

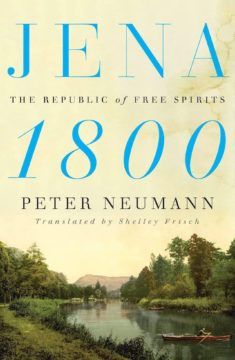

EARLY IN ELIF BATUMAN’S NEW NOVEL Either/Or, she quotes a blurb on the front of Kazuo Ishiguro’s An Artist of the Floating World, extracted from its 1986 review in the New York Times. “Good writers abound—good novelists are very rare,” the critic theorizes, deeming Ishiguro “not only a good writer, but also a wonderful novelist.” For Either/Or’s narrator, the distinction comes as a shock. Since she was young, Selin has aspired to become a novelist, and she views much of her life to date as training for that vocation. Assessing herself according to the reviewer’s implied rubric, Selin realizes that her facility with language, her sparkling insights and clever turns of phrase, may not be sufficient. “It was what I had been counting on,” she thinks. “My sense of being a good writer. My stomach sank with the knowledge of how wrong I had been.” This is in some sense the anxiety that haunts Either/Or: Batuman is demonstrably, incontrovertibly a good writer—but is she a good novelist? (And what is a good novel anyway?) No wonder, too, then, that there is a current public of soi-disant intellectuals eager to learn about past experiments in living, especially those with a significant philosophical dimension. And so we have Peter Neumann’s Jena 1800: The Republic of Free Spirits (translated by Shelley Frisch), “a fascinating and highly readable story of ideas, art, love, and war,” as one blurb has it, and a picture of “a world intoxicated with the possibilities of thought,” according to another. Jena in 1798 to 1800 was a backwater provincial city of 5,000 residents, one-fifth of whom were students. Initially attracted by the presences at the university first of Karl Leonhard Reinhold and then J. G. Fichte, both of whom were associated with the free thinking of Kantianism and the French Revolution, a circle of intellectual friends, including women as equals as well as men, formed around the brothers August and Friedrich Schlegel.

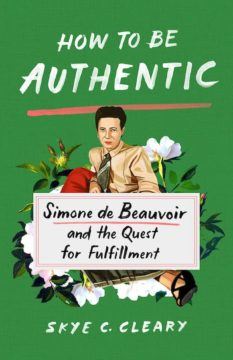

No wonder, too, then, that there is a current public of soi-disant intellectuals eager to learn about past experiments in living, especially those with a significant philosophical dimension. And so we have Peter Neumann’s Jena 1800: The Republic of Free Spirits (translated by Shelley Frisch), “a fascinating and highly readable story of ideas, art, love, and war,” as one blurb has it, and a picture of “a world intoxicated with the possibilities of thought,” according to another. Jena in 1798 to 1800 was a backwater provincial city of 5,000 residents, one-fifth of whom were students. Initially attracted by the presences at the university first of Karl Leonhard Reinhold and then J. G. Fichte, both of whom were associated with the free thinking of Kantianism and the French Revolution, a circle of intellectual friends, including women as equals as well as men, formed around the brothers August and Friedrich Schlegel. Although existentialist philosophers rarely labeled themselves as such or agreed on a definition of what they were doing, existentialism is a coherent and sound philosophy. It begins with the claim that “existence precedes essence,” meaning that people enter the world (they exist) before they can be said to have a fixed definition (or essence). They are free to create their own essence, and with this freedom comes responsibility. The contrast between how strange it is to exist and the reality that we are here is called “absurdity.” From absurdity, nihilists would avow that life is meaningless, and thus do whatever they want. Existentialists, however, typically reject nihilism and embrace authenticity. For Martin Heidegger, authenticity was related to our “being toward death.” For Friedrich Nietzsche, the “eternal return of the same” counsels us to live as if our life will repeat itself eternally.

Although existentialist philosophers rarely labeled themselves as such or agreed on a definition of what they were doing, existentialism is a coherent and sound philosophy. It begins with the claim that “existence precedes essence,” meaning that people enter the world (they exist) before they can be said to have a fixed definition (or essence). They are free to create their own essence, and with this freedom comes responsibility. The contrast between how strange it is to exist and the reality that we are here is called “absurdity.” From absurdity, nihilists would avow that life is meaningless, and thus do whatever they want. Existentialists, however, typically reject nihilism and embrace authenticity. For Martin Heidegger, authenticity was related to our “being toward death.” For Friedrich Nietzsche, the “eternal return of the same” counsels us to live as if our life will repeat itself eternally.

In my nine years of doing this work I have seen an increasing demonisation of the clients of sex workers, even while I’ve seen increasing support for sex workers themselves. Much of the discussion around sex-worker rights focuses on the workers, how often marginalised people enter the industry out of financial necessity, and how criminalising that only further marginalises them, by forcing them into more dangerous scenarios and punishing them for their need. All this is of course of pre-eminent importance. And I think that the rights of sex workers shouldn’t rely on the value or respectability of the work itself—it is simply a human rights and labour rights issue. Sex workers should be able to speak about exploitation and abuse in the industry without that being used against us to argue for the eradication of the industry itself—in the same way migrant workers are speaking about working conditions on Australian farms without it leading to a cry to shut down agriculture.

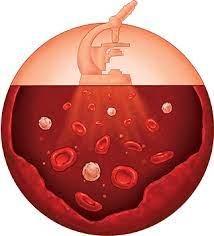

In my nine years of doing this work I have seen an increasing demonisation of the clients of sex workers, even while I’ve seen increasing support for sex workers themselves. Much of the discussion around sex-worker rights focuses on the workers, how often marginalised people enter the industry out of financial necessity, and how criminalising that only further marginalises them, by forcing them into more dangerous scenarios and punishing them for their need. All this is of course of pre-eminent importance. And I think that the rights of sex workers shouldn’t rely on the value or respectability of the work itself—it is simply a human rights and labour rights issue. Sex workers should be able to speak about exploitation and abuse in the industry without that being used against us to argue for the eradication of the industry itself—in the same way migrant workers are speaking about working conditions on Australian farms without it leading to a cry to shut down agriculture. They span three continents, but a trio of researchers who’ve never met share a singular focus made vital by the still-raging pandemic: deciphering the causes of Long Covid and figuring out how to treat it.

They span three continents, but a trio of researchers who’ve never met share a singular focus made vital by the still-raging pandemic: deciphering the causes of Long Covid and figuring out how to treat it. On March 9, 1945, an armada of more than three hundred B-29s flew fifteen hundred miles across the Pacific to attack Tokyo from the air. The planes carried incendiary bombs to be dropped at low altitudes. Beginning shortly after midnight, sixteen hundred and sixty-five tons of bombs fell on the city.

On March 9, 1945, an armada of more than three hundred B-29s flew fifteen hundred miles across the Pacific to attack Tokyo from the air. The planes carried incendiary bombs to be dropped at low altitudes. Beginning shortly after midnight, sixteen hundred and sixty-five tons of bombs fell on the city. S

S PAINTED IN THE 1950S on the walls of her sons’ bedroom and later collected in a children’s book called The Milk of Dreams, Leonora Carrington’s wicked fairy tales inspired the title and tenor of the Fifty-Ninth Venice Biennale. Filled with disobedient children, deviant friendships, orphaned monsters, evil crones, sentient meat, hungry furniture, misplaced heads, scatological warfare, and pharmacological magic, Carrington’s stories struck curator Cecilia Alemani for their construction of what she describes as “a world free of hierarchies, where everyone can become something else.” Alemani endeavored to create something like this world in her beautiful and perturbing exhibition, and to a great degree she has succeeded.

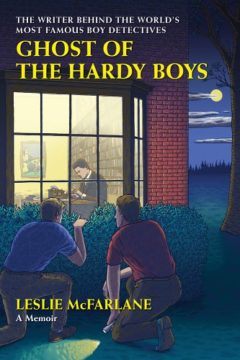

PAINTED IN THE 1950S on the walls of her sons’ bedroom and later collected in a children’s book called The Milk of Dreams, Leonora Carrington’s wicked fairy tales inspired the title and tenor of the Fifty-Ninth Venice Biennale. Filled with disobedient children, deviant friendships, orphaned monsters, evil crones, sentient meat, hungry furniture, misplaced heads, scatological warfare, and pharmacological magic, Carrington’s stories struck curator Cecilia Alemani for their construction of what she describes as “a world free of hierarchies, where everyone can become something else.” Alemani endeavored to create something like this world in her beautiful and perturbing exhibition, and to a great degree she has succeeded. This example of calmness in the face of disaster didn’t really help. It was all very well for Dave Fearless to meet catastrophe with aplomb. He could count on Bob Vilett and Captain Broadbeam to haul him to the surface, while Pat Stoodles lent encouragement by bellowing “Heave-ho, bejabers!” I couldn’t count on anyone—except, perhaps, Edward Stratemeyer.

This example of calmness in the face of disaster didn’t really help. It was all very well for Dave Fearless to meet catastrophe with aplomb. He could count on Bob Vilett and Captain Broadbeam to haul him to the surface, while Pat Stoodles lent encouragement by bellowing “Heave-ho, bejabers!” I couldn’t count on anyone—except, perhaps, Edward Stratemeyer. The COVID-19 pandemic was foreseen. Experts everywhere had long predicted a global viral outbreak and called for action to prevent it. World leaders, on the whole, did little. Now, with COVID-19 still raging, Bill Gates has produced a manifesto on what must be done to prevent the next pandemic. Written in accessible prose that even a busy world leader could not fail to grasp, the global-health philanthropist offers some life-saving ideas that are ambitious and achievable — if political leaders act.

The COVID-19 pandemic was foreseen. Experts everywhere had long predicted a global viral outbreak and called for action to prevent it. World leaders, on the whole, did little. Now, with COVID-19 still raging, Bill Gates has produced a manifesto on what must be done to prevent the next pandemic. Written in accessible prose that even a busy world leader could not fail to grasp, the global-health philanthropist offers some life-saving ideas that are ambitious and achievable — if political leaders act. A student once asked—after a classroom discussion of how 19th-century westward expansion connected to the ongoing injustices of American military bases in the Pacific—what she was supposed to do with this knowledge. Her question was as genuine as it was perceptive. It also felt like I had, again, failed.

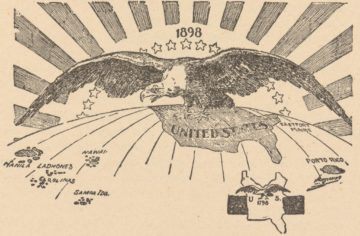

A student once asked—after a classroom discussion of how 19th-century westward expansion connected to the ongoing injustices of American military bases in the Pacific—what she was supposed to do with this knowledge. Her question was as genuine as it was perceptive. It also felt like I had, again, failed.