Becky Y. Lu at Hudson Review:

Surrealism is having a moment. It is the theme of this year’s Venice Biennale and was that of last winter’s major exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Absurdist, dystopic shows like Severance (Apple TV+) and Russian Doll (Netflix) are resonating with audiences and critics. René Magritte’s L’empire des lumières (1961) fetched a record price recently at auction. And why not, for we are besieged by surrealities, both serious and comical, almost daily: the potential resurgence of underground abortions in the U.S., Will Smith slapping Chris Rock at the Oscars, Russia’s continued assault of Ukraine, the histrionics of Elon Musk’s flailing Twitter takeover, senseless deaths from unnecessary guns, Partygate at 10 Downing Street, the airlifting of infant formula into the richest country in history, the rise of autocracy, and so on. The chaos that crowds our newsfeeds seems to belong to another century, if not an alternate universe.

Surrealism is having a moment. It is the theme of this year’s Venice Biennale and was that of last winter’s major exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Absurdist, dystopic shows like Severance (Apple TV+) and Russian Doll (Netflix) are resonating with audiences and critics. René Magritte’s L’empire des lumières (1961) fetched a record price recently at auction. And why not, for we are besieged by surrealities, both serious and comical, almost daily: the potential resurgence of underground abortions in the U.S., Will Smith slapping Chris Rock at the Oscars, Russia’s continued assault of Ukraine, the histrionics of Elon Musk’s flailing Twitter takeover, senseless deaths from unnecessary guns, Partygate at 10 Downing Street, the airlifting of infant formula into the richest country in history, the rise of autocracy, and so on. The chaos that crowds our newsfeeds seems to belong to another century, if not an alternate universe.

It was perhaps no coincidence, then, that the Metropolitan Opera revived Jonathan Miller’s Surrealist, fin-de-siècle take on Igor Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress.

more here.

“We have heard that when it arrived in Europe, zero was treated with suspicion. We don’t think of the absence of sound as a type of sound, so why should the absence of numbers be a number, argued its detractors. It took centuries for zero to gain acceptance. It is certainly not like other numbers. To work with it requires some tough intellectual contortions, as mathematician Ian Stewart explains.

“We have heard that when it arrived in Europe, zero was treated with suspicion. We don’t think of the absence of sound as a type of sound, so why should the absence of numbers be a number, argued its detractors. It took centuries for zero to gain acceptance. It is certainly not like other numbers. To work with it requires some tough intellectual contortions, as mathematician Ian Stewart explains. Donald Trump says Republican voters sent Liz Cheney to “political oblivion” with her crushing election defeat at the hands of a candidate he endorsed. But not so fast – here’s how one of the former president’s biggest critics could still hurt him if he runs for re-election.

Donald Trump says Republican voters sent Liz Cheney to “political oblivion” with her crushing election defeat at the hands of a candidate he endorsed. But not so fast – here’s how one of the former president’s biggest critics could still hurt him if he runs for re-election. More than once I’ve been told by successful writers that if I wanted to become a writer, I should copy out by hand my favorite novel. “You have to write out the entire thing,” one of them told me. “You can’t imagine how illuminating it can be.” I’ve never done this exercise myself, but I believe that I’ve experienced its intended effect doing literary translations. Translating a novel was a formative experience for me as a writer because I learned that writing is like any other art: while talent can’t be taught, technique can be learned. So, how exactly does one learn technique? I decided to take creative writing classes, earning my Certificate in Creative Writing from UCLA Extension and attending classes through Stanford Continuing Education’s program, as well as a handful of other writing centers. It was then that I experienced the creative writing workshop for myself.

More than once I’ve been told by successful writers that if I wanted to become a writer, I should copy out by hand my favorite novel. “You have to write out the entire thing,” one of them told me. “You can’t imagine how illuminating it can be.” I’ve never done this exercise myself, but I believe that I’ve experienced its intended effect doing literary translations. Translating a novel was a formative experience for me as a writer because I learned that writing is like any other art: while talent can’t be taught, technique can be learned. So, how exactly does one learn technique? I decided to take creative writing classes, earning my Certificate in Creative Writing from UCLA Extension and attending classes through Stanford Continuing Education’s program, as well as a handful of other writing centers. It was then that I experienced the creative writing workshop for myself. Even a small conflict in which two nations unleash nuclear weapons on each other could lead to worldwide famine, new research suggests. Soot from burning cities would encircle the planet and cool it by reflecting sunlight back into space. This in turn would cause global crop failures that — in a worst-case scenario — could put 5 billion people on the brink of death.

Even a small conflict in which two nations unleash nuclear weapons on each other could lead to worldwide famine, new research suggests. Soot from burning cities would encircle the planet and cool it by reflecting sunlight back into space. This in turn would cause global crop failures that — in a worst-case scenario — could put 5 billion people on the brink of death. As probably will surprise no one, the polarization spiral between the left and the right has only gotten more intense in the last three years. Most alarming is the growing acceptance of political violence as a justifiable method for achieving political goals. A survey in 2019 found that approximately one-fifth of partisans in both parties believed that

As probably will surprise no one, the polarization spiral between the left and the right has only gotten more intense in the last three years. Most alarming is the growing acceptance of political violence as a justifiable method for achieving political goals. A survey in 2019 found that approximately one-fifth of partisans in both parties believed that  Why do people keep falling for hoaxes?

Why do people keep falling for hoaxes? All living cells power themselves by coaxing energetic electrons from one side of a membrane to the other. Membrane-based mechanisms for accomplishing this are, in a sense, as universal a feature of life as the genetic code. But unlike the genetic code, these mechanisms are not the same everywhere: The two simplest categories of cells, bacteria and archaea, have membranes and protein complexes for producing energy that are chemically and structurally dissimilar. Those differences make it hard to guess how the very first cells met their energy needs.

All living cells power themselves by coaxing energetic electrons from one side of a membrane to the other. Membrane-based mechanisms for accomplishing this are, in a sense, as universal a feature of life as the genetic code. But unlike the genetic code, these mechanisms are not the same everywhere: The two simplest categories of cells, bacteria and archaea, have membranes and protein complexes for producing energy that are chemically and structurally dissimilar. Those differences make it hard to guess how the very first cells met their energy needs. 2022 has been a year of dollar power—power that manifests itself in both overt and subtler forms.

2022 has been a year of dollar power—power that manifests itself in both overt and subtler forms. In 1982, a fifty-four-year-old

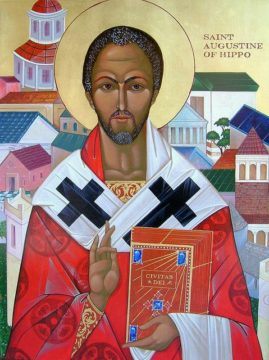

In 1982, a fifty-four-year-old  I learned about Augustine of Hippo from my mother. She had memorized lines from his Confessions as a Catholic schoolgirl in the Caribbean village of Manatí in Colombia. “Our hearts are restless until they rest in God,” she would tell me. Even after she immigrated to the United States and became a born-again Protestant, she kept reciting him. When I left my home on Long Island to study philosophy at a liberal arts college out of state, her prayers followed me just as Monica’s trailed her son, Augustine, when he boarded a ship heading for Italy. I joked that she was my Monica. But I gradually developed my own relationship to Augustine. As I encountered him in a predominantly white academic setting, I latched on to him. He became more than the metaphysical or doctrinal positions parsed in class. Augustine was the symbol of a more diverse and global Christianity that had been covered up by white-supremacist lies. “The greatest thinkers of the early Church came from Africa!” I declared to amused peers. My Augustine was Black.

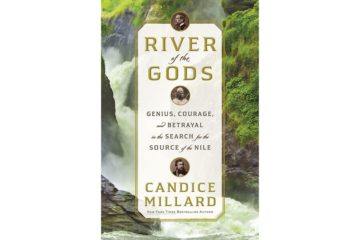

I learned about Augustine of Hippo from my mother. She had memorized lines from his Confessions as a Catholic schoolgirl in the Caribbean village of Manatí in Colombia. “Our hearts are restless until they rest in God,” she would tell me. Even after she immigrated to the United States and became a born-again Protestant, she kept reciting him. When I left my home on Long Island to study philosophy at a liberal arts college out of state, her prayers followed me just as Monica’s trailed her son, Augustine, when he boarded a ship heading for Italy. I joked that she was my Monica. But I gradually developed my own relationship to Augustine. As I encountered him in a predominantly white academic setting, I latched on to him. He became more than the metaphysical or doctrinal positions parsed in class. Augustine was the symbol of a more diverse and global Christianity that had been covered up by white-supremacist lies. “The greatest thinkers of the early Church came from Africa!” I declared to amused peers. My Augustine was Black. It was a geographical mystery that had befuddled explorers, astronomers, and philosophers for two millennia: Where did the Nile begin? In “River of the Gods: Genius, Courage, and Betrayal in the Search for the Source of the Nile,” historian Candice Millard recounts the adventures of two ambitious, Victorian-era rivals who spent years trekking through East Africa, enduring unimaginable hardships, in an effort to be the first to solve the puzzle.

It was a geographical mystery that had befuddled explorers, astronomers, and philosophers for two millennia: Where did the Nile begin? In “River of the Gods: Genius, Courage, and Betrayal in the Search for the Source of the Nile,” historian Candice Millard recounts the adventures of two ambitious, Victorian-era rivals who spent years trekking through East Africa, enduring unimaginable hardships, in an effort to be the first to solve the puzzle. The ability of the brain to create consciousness has baffled some for millennia. The mystery of consciousness lies in the fact that each of us has subjectivity, something that is like to sense, feel and think. In contrast to being under anesthesia or in a dreamless deep sleep, while we’re awake we don’t “live in the dark” — we experience the world and ourselves. But how the brain creates the conscious experience and what area of the brain is responsible for this remains a mystery. According to Dr. Nir Lahav, a physicist from Bar-Ilan University in Israel, “This is quite a mystery since it seems that our conscious experience cannot arise from the brain, and in fact, cannot arise from any physical process.”

The ability of the brain to create consciousness has baffled some for millennia. The mystery of consciousness lies in the fact that each of us has subjectivity, something that is like to sense, feel and think. In contrast to being under anesthesia or in a dreamless deep sleep, while we’re awake we don’t “live in the dark” — we experience the world and ourselves. But how the brain creates the conscious experience and what area of the brain is responsible for this remains a mystery. According to Dr. Nir Lahav, a physicist from Bar-Ilan University in Israel, “This is quite a mystery since it seems that our conscious experience cannot arise from the brain, and in fact, cannot arise from any physical process.” The Satanic Verses, Rushdie’s fourth novel, was as much an exploration of the migrant experience as it was about Islam, as savage in its indictment of racism as of religion. What mattered, though, was less what Rushdie wrote than what the novel came to symbolise. The 1980s was a decade that saw the beginnings of the breakdown of traditional political and moral boundaries, an unravelling with which we are still coming to terms.

The Satanic Verses, Rushdie’s fourth novel, was as much an exploration of the migrant experience as it was about Islam, as savage in its indictment of racism as of religion. What mattered, though, was less what Rushdie wrote than what the novel came to symbolise. The 1980s was a decade that saw the beginnings of the breakdown of traditional political and moral boundaries, an unravelling with which we are still coming to terms.