Category: Recommended Reading

Flooded with AI-generated images, some art communities ban them completely

Benj Edwards in Ars Technica:

The arrival of widely available image synthesis models such as Midjourney and Stable Diffusion has provoked an intense online battle between artists who view AI-assisted artwork as a form of theft (more on that below) and artists who enthusiastically embrace the new creative tools.

The arrival of widely available image synthesis models such as Midjourney and Stable Diffusion has provoked an intense online battle between artists who view AI-assisted artwork as a form of theft (more on that below) and artists who enthusiastically embrace the new creative tools.

Established artist communities are at a tough crossroads because they fear non-AI artwork getting drowned out by an unlimited supply of AI-generated art, and yet the tools have also become notably popular among some of their members.

In banning art created through image synthesis in its Art Portal, Newgrounds wrote, “We want to keep the focus on art made by people and not have the Art Portal flooded with computer-generated art.”

More here.

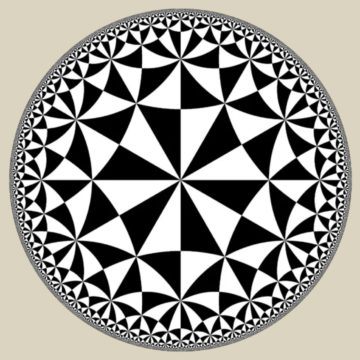

Theoretical physicist Sean Carroll visualizes a mind-bending geometry that inspired many, from Einstein to Escher

Sean Carroll in Pioneer Works:

Of Euclid’s five postulates, which form the basis of Euclidean geometry, the fifth is the most controversial. Called the Parallel Postulate, it’s a pretty basic idea. Take a flat piece of paper, draw a line segment and then draw two lines that are perpendicular to it. The Parallel Postulate simply says that the lines will remain forever parallel, staying precisely the same distance apart even if we extend them to infinity on either side of the line segment.

Of Euclid’s five postulates, which form the basis of Euclidean geometry, the fifth is the most controversial. Called the Parallel Postulate, it’s a pretty basic idea. Take a flat piece of paper, draw a line segment and then draw two lines that are perpendicular to it. The Parallel Postulate simply says that the lines will remain forever parallel, staying precisely the same distance apart even if we extend them to infinity on either side of the line segment.

For a long time mathematicians strived to prove the Parallel Postulate using the first four (more) basic postulates, and so elevate it from a postulated axiom to a proven theorem. It turns out that you can’t, and for good reason—the postulate isn’t true for all geometries. Euclidean geometry, represented by the flat piece of paper, and on which lines that start off parallel never intersect, is just one kind of geometry, but there are others. You can imagine replacing the Parallel Postulate with some alternative: maybe lines that are parallel initially draw closer together and touch eventually, or maybe they always move apart. The first option is the case with spherical geometry, which describes shapes drawn on the surface of a sphere (think of lines of longitude that start of parallel at the equator but converge at the poles), while the second defines hyperbolic geometry, which is more like the surface of a saddle or a Pringle’s potato chip.

These non-Euclidean alternatives weren’t noticed for millennia. Euclid himself flourished around 300 BCE, and the first alternatives to the Parallel Postulate were proposed in the early 1800s by Russian mathematician Nikolai Lobachevsky and Hungarian mathematician János Bolyai. Interestingly, both studied the hyperbolic alternative to flat Euclidean geometry.

This raises two questions: First, why did it take so long? And second, why did the mathematicians study hyperbolic geometry before spherical? Everyone knew about spheres. How hard could it have been to imagine drawing some lines on them, and exploring the geometric consequences of doing so?

The questions share a common answer.

More here.

Janus’ GPT Wrangling

Scott Alexander in Astral Codex Ten:

Janus (pseudonym by request) works at AI alignment startup Conjecture. Their hobby, which is suspiciously similar to their work, is getting GPT-3 to do interesting things.

For example, with the right prompts, you can get stories where the characters become gradually more aware that they are characters being written by some sort of fiction engine, speculate on what’s going on, and sometimes even make pretty good guesses about the nature of GPT-3 itself.

Janus says this happens most often when GPT makes a mistake – for example, writing a story set in the Victorian era, then having a character take out her cell phone. Then when it tries to predict the next part – when it’s looking at the text as if a human wrote it, and trying to determine why a human would have written a story about the Victorian era where characters have cell phones – it guesses that maybe it’s some kind of odd sci-fi/fantasy dream sequence or simulation or something. So the characters start talking about the inconsistencies in their world and whether it might be a dream or a simulation. Each step of this process is predictable and non-spooky, but the end result is pretty weird.

Can the characters work out that they are in GPT-3, specifically?

More here.

Time doesn’t flow like a river. So why do we feel swept along?

Nick Young in Psyche:

As you read this article, time will seem to pass. Right now, you are reading these words, but now you are reading these ones. What was present just an instant ago seems to have already slipped into the past. You will carry this feeling with you – as objects change and move, as thoughts run through your head, as feelings ebb and flow – until you fall asleep tonight. Heraclitus thought that time was like a river: ‘Everything flows and nothing abides; everything gives way and nothing stays fixed.’ Our experience of the world seems to back this up. It certainly feels as if time is sweeping us along. Yet, physicists and philosophers will tell you that Heraclitus was wrong. Time, they say, does not actually pass. In his book The Order of Time (2018), the Italian theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli writes:

As you read this article, time will seem to pass. Right now, you are reading these words, but now you are reading these ones. What was present just an instant ago seems to have already slipped into the past. You will carry this feeling with you – as objects change and move, as thoughts run through your head, as feelings ebb and flow – until you fall asleep tonight. Heraclitus thought that time was like a river: ‘Everything flows and nothing abides; everything gives way and nothing stays fixed.’ Our experience of the world seems to back this up. It certainly feels as if time is sweeping us along. Yet, physicists and philosophers will tell you that Heraclitus was wrong. Time, they say, does not actually pass. In his book The Order of Time (2018), the Italian theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli writes:

What could be more universal and obvious than this flowing?

And yet things are somewhat more complicated than this. Reality is often very different from what it seems. The Earth appears to be flat but is in fact spherical. The Sun seems to revolve in the sky when it is really we who are spinning. Neither is the structure of time what it seems to be: it is different from this uniform, universal flowing.

So, what is the real structure of time? Well, it’s complicated.

More here.

Saturday, September 24, 2022

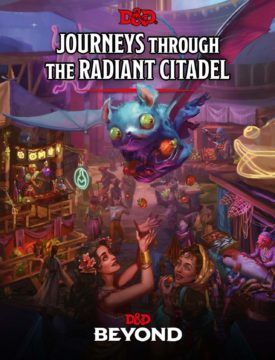

A Fierce, Fragile Utopia: A Conversation with Ajit A. George

David M. Higgins talks to Ajit George in LA Review of Books:

David M. Higgins talks to Ajit George in LA Review of Books:

JOURNEYS THROUGH THE RADIANT CITADEL is the first Dungeons & Dragons product of its kind in the game’s nearly 50-year history written entirely by authors of color. In addition to the 16 Black and Brown writers who contributed to this groundbreaking adventure anthology, other people of color who contributed to the book include the co–art director, two rules developers, one editor, the marketing director, a multitude of consultants and researchers, and two-thirds of all the artists (including both cover artists).

The visionary behind this project is Ajit A. George, who served as creator, co–project lead, and co-writer for the book. Outside the gaming world, George is the director of operations for the international nonprofit the Shanti Bhavan Children’s Project. He has spoken for TEDx, the International Monetary Fund, and NPR on topics including education, gender equality, community development, and poverty alleviation. As a game creator, he graduated from the Clarion West Writers Workshop, and he has written for a variety of gaming companies such as Bully Pulpit, Thorny Games, and Monte Cook Games. He has also organized international collaborative live-action role-playing events, and he is an energetic diversity consultant, speaker, and activist.

More here.

Servants No Longer: On Civic Friendship

From a conservative but unorthodox side of the spectrum, Chris Griswold in American Compass:

Aristotle uses the term “civic friendship” to describe the bonds that emerge from a sense of common purpose in a shared political project. “Citizens are civic friends,” the Aristotelian philosopher Paul Ludwig writes, “when they share an agreement about important practical matters: preeminently, they agree about the regime, their political system.” Communal commitment to a common endeavour results in a kind of general goodwill of citizens toward one another—the seeds of civic friendship. It is what allows a society to remain whole and undivided rather than fragmenting into warring subcommunities. It is also a good description of what American life so conspicuously lacks.

How, though, does a society ensure that its members do believe themselves to be in it together, with common goals and shared outcomes? In December 1961, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered remarks to the Fourth AFL-CIO Constitutional Convention in Miami Beach, and attempted to answer that question.

King was stepping into a heated and challenging situation. The AFL-CIO was plagued by internal acrimony and public hesitation regarding civil rights. King chose to address the tension directly. He told the assembled delegates that the civil rights and labor movements had to work together, because their aims were inseparable. Democracy was not complete and could not remain stable without a working public empowered to fully participate in the nation’s economic life. A voice at the ballot box represented only incomplete equality without a collective voice in the workplace.

More here.

The Genizah of the Self

Marco Roth in Tablet:

Marco Roth in Tablet:

Over a year ago—it was last Tisha B’Av—I found myself moving house for the third time since 2019. This move was the big one, resulting from the sale of the apartment in Philadelphia that my wife and I had bought together, renovated together, and had lived in for six mostly happy years and three mostly difficult ones. From the spring of 2020, we’d rented it out, furnished, once we began the final unraveling of our common life. Moves bring inevitable reckonings, moves like these exceptionally so.

Amid the furniture, the books, the rugs, and various objects—both those I’d acquired independently and those passed down from ancestors—I kept five boxes, two of them equal parts tape and cardboard, containing an archive of my mental life, or at least my professional mental life. There was a box full of contracts for various articles and my book contract, drafts of that first and so far only book with copy-editor marks. Here were all the college and grad school syllabi and papers; notebooks from 10 years of higher education; xeroxed articles from course packets and research; graded tests; graded papers with comments; drafts of early, never-completed stories on legal notepads; drafts of my never-completed Ph.D. dissertation; there was my undergraduate thesis on Proust; my first semester graduate school paper on Benjamin’s Arcades Project; all the worksheets and tests for the “Italian for Reading Knowledge” summer intensive course I’d needed to pass my last language requirement; there was that undergrad paper with a professor’s telling remark, “brilliant but self-defeating,” a memento from a riskier and more insightful era of student-teacher relations.

How could I possibly hold on to all this stuff? What purpose did I think it served? It’s not as if I intended to return to my Ph.D. research at this point in my life, although all of it was in there, somewhere.

More here.

Saul Kripke, Philosopher Who Found Truths in Semantics, Dies at 81

Sam Roberts in the New York Times:

Sam Roberts in the New York Times:

Saul Kripke, a math prodigy and pioneering logician whose revolutionary theories on language qualified him as one of the 20th century’s greatest philosophers, died on Sept. 15 in Plainsboro, N.J. He was 81.

His death, at Penn Medicine Princeton Medical Center, was caused by pancreatic cancer, according to Romina Padro, director of the Saul Kripke Center at the City University of New York, where Professor Kripke had been a distinguished professor of philosophy and computer science since 2003 and had capped a career exploring how people communicate.

Professor Kripke’s classic work, “Naming and Necessity,” first published in 1972 and drawn from three lectures he delivered at Princeton University in 1970 before he was 30, was considered one of the century’s most evocative philosophical books.

“Kripke challenged the notion that anyone who uses terms, especially proper names, must be able to correctly identify what the terms refer to,” said Michael Devitt, a distinguished professor of philosophy who recruited Professor Kripke to the City University Graduate Center in Manhattan.

“Rather, people can use terms like ‘Einstein,’ ‘springbok,’ perhaps even ‘computer,’ despite being too ignorant or wrong to provide identifying descriptions of their referents,” Professor Devitt said. “We can use terms successfully not because we know much about the referent but because we’re linked to the referent by a great social chain of communication.”

More here.

The Power of Positive Declassifying

Anand Giridharadas in The New Yorker:

There is a secret. And that secret is how to make top-secret secrets not secret anymore using only your mind. All that stands between you and doing this is embracing the power of positive declassifying. Let others submit formal written declassification requests to the proper agencies. You are special. You are powerful. You are going to jail. The first step is gratitude. Close your eyes—but also maybe keep one open for the F.B.I.—and say meaningful thank-yous to those whose service you will be betraying.

There is a secret. And that secret is how to make top-secret secrets not secret anymore using only your mind. All that stands between you and doing this is embracing the power of positive declassifying. Let others submit formal written declassification requests to the proper agencies. You are special. You are powerful. You are going to jail. The first step is gratitude. Close your eyes—but also maybe keep one open for the F.B.I.—and say meaningful thank-yous to those whose service you will be betraying.

Picture each spy in your mind and thank them for their heroic and unsung work—whether it was long years spent pretending to be Vladimir Putin’s “sports masseuse” or a terrifying night in an Iranian nuclear facility spent replacing uranium with a slurry of crushed Cheetos and Mountain Dew. Then, with your heart full of appreciation, hum—more of a flat “mm” here, as “om” is now considered a little appropriative—and visualize each agent you may be sending to an untimely death. Now chant, in your mind, I declassify, I declassify, with my mind, I declassify.

More here.

I measure every Grief I meet

Emily Dickinson in Poets.org:

I measure every Grief I meet With narrow, probing, eyes – I wonder if It weighs like Mine – Or has an Easier size. I wonder if They bore it long – Or did it just begin – I could not tell the Date of Mine – It feels so old a pain – I wonder if it hurts to live – And if They have to try – And whether – could They choose between – It would not be – to die – More here.

Saturday Poem

Trees

Trees know these things –

how to survive by bending with the wind

stretching roots to quench thirst.

When branches break from winter’s wet snow,

trees know how to heal wounds

make do with what remains.

They even know how to die with grace, rotting back to soft earth,

offering themselves for what comes next.

If I could today

I would become that tree,

poised in front of this green metal chair

where I sit this early spring afternoon.

Empty of color,

its branches wait patiently for their blossoming

as months from now they will accept their dying back to grey.

Clinging to this craggy hillside

it stands tall, crooked, framed by endless sky above,

steadfast ground beneath.

If I could today

I would borrow this tree’s belonging in the world.

Stephanie Shafran

from the Bouttelle-Day Poetry Center

Smith College, Northampton Ma.

‘Life Is Hard’ By Kieran Setiya

Anil Gomes at The Guardian:

Philosophy’s role here is not primarily analytical. We cannot be argued into coping with suffering. Instead, Setiya’s book is guided by an insight from Iris Murdoch: that philosophical progress often consists of finding new and better ways to describe some stretch of our experience. This kind of progress is not won by logic. It requires careful attention, precise thinking and the ability to draw distinctions that cast light on that which is of value. Setiya is at his best when he has something or someone clearly in view – for example in his account of living with chronic pain, or his discussion of the philosopher and mystic Simone Weil.

Philosophy’s role here is not primarily analytical. We cannot be argued into coping with suffering. Instead, Setiya’s book is guided by an insight from Iris Murdoch: that philosophical progress often consists of finding new and better ways to describe some stretch of our experience. This kind of progress is not won by logic. It requires careful attention, precise thinking and the ability to draw distinctions that cast light on that which is of value. Setiya is at his best when he has something or someone clearly in view – for example in his account of living with chronic pain, or his discussion of the philosopher and mystic Simone Weil.

And if the prescriptions sometimes seem a little pat, that is a danger inherent to the project. Setiya’s targets are the infirmities of human life in general, but many of the problems that bedevil us are as individual as we are.

more here.

Philosophy And The Good Life: A Conversation With Kieran Setiya

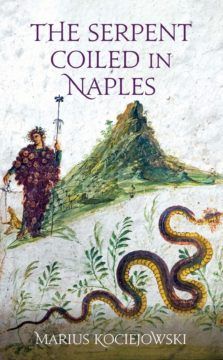

A Search For The Soul Of Naples

Claudia Roth Pierpont at The New Yorker:

One day a few years ago, an Englishman walked into a tourist shop on the ground floor of a Neapolitan palazzo and told a woman he encountered there that he was searching for the soul of Naples. The building, named Palazzo del Panormita, for an obscure fifteenth-century author of erotic Latin epigrams, stands near a small piazza named for the River Nile, recalling the Egyptian traders who once lived in a mini-quarter within the city center’s ancient Greek grid. (There was a Greek settlement there before the Parthenon was built.) Today, that grid runs into a thoroughfare cut by the Spanish in the sixteenth century, when the Kingdom of Naples was under their imperial control. Named Via Toledo by the Spanish, the street became Via Roma three centuries later, when Naples, at last free of a series of foreign overlords, joined a unified Italy. And yet for many Neapolitans the idea of being governed from Rome was apparently as abhorrent as Spanish dominion: the name Via Roma aroused so much resentment that, in the nineteen-eighties, the city brought the old Spanish name back into official use. Even now, Neapolitans differ sharply on what their central commercial street should be called.

One day a few years ago, an Englishman walked into a tourist shop on the ground floor of a Neapolitan palazzo and told a woman he encountered there that he was searching for the soul of Naples. The building, named Palazzo del Panormita, for an obscure fifteenth-century author of erotic Latin epigrams, stands near a small piazza named for the River Nile, recalling the Egyptian traders who once lived in a mini-quarter within the city center’s ancient Greek grid. (There was a Greek settlement there before the Parthenon was built.) Today, that grid runs into a thoroughfare cut by the Spanish in the sixteenth century, when the Kingdom of Naples was under their imperial control. Named Via Toledo by the Spanish, the street became Via Roma three centuries later, when Naples, at last free of a series of foreign overlords, joined a unified Italy. And yet for many Neapolitans the idea of being governed from Rome was apparently as abhorrent as Spanish dominion: the name Via Roma aroused so much resentment that, in the nineteen-eighties, the city brought the old Spanish name back into official use. Even now, Neapolitans differ sharply on what their central commercial street should be called.

more here.

Friday, September 23, 2022

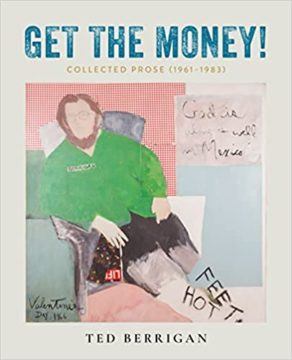

On Ted Berrigan’s Exuberant And Idiosyncratic Prose

Jordan Davis at Poetry Magazine:

Though there is less of Berrigan’s prose than his poetry, the best of it—his early journals, the collaged “interview” with John Cage from 1966, the Chicago Report and the Boston journal—has been crying out to be collected for decades. With the publication of Get the Money!: Collected Prose 1961-1983 (City Lights, 2022), edited by Berrigan’s widow, Alice Notley, their sons Edmund and Anselm Berrigan, and scholar Nick Sturm, readers already familiar with the pleasures of the self-made poet have a new, single-volume resource to consult. This great book stands alongside Berrigan’s Collected Poems (2007); On the Level Everyday (1997), his collected lectures; and Talking in Tranquility (1991), his collected interviews. The book may not teach readers how to interpret or analyze poetry in a way that will impress comparative literature professors, but every page offers a sense of what a living, noninstitutional poetry community looks and sounds like. Over the book’s more than 20-year span, we see when that community is doing well—attracting new recruits, producing new poetic forms—and when it’s under strain as consensus emerges and chance intervenes to support some members but not others, and money and attention accumulate at a slower rate.

Though there is less of Berrigan’s prose than his poetry, the best of it—his early journals, the collaged “interview” with John Cage from 1966, the Chicago Report and the Boston journal—has been crying out to be collected for decades. With the publication of Get the Money!: Collected Prose 1961-1983 (City Lights, 2022), edited by Berrigan’s widow, Alice Notley, their sons Edmund and Anselm Berrigan, and scholar Nick Sturm, readers already familiar with the pleasures of the self-made poet have a new, single-volume resource to consult. This great book stands alongside Berrigan’s Collected Poems (2007); On the Level Everyday (1997), his collected lectures; and Talking in Tranquility (1991), his collected interviews. The book may not teach readers how to interpret or analyze poetry in a way that will impress comparative literature professors, but every page offers a sense of what a living, noninstitutional poetry community looks and sounds like. Over the book’s more than 20-year span, we see when that community is doing well—attracting new recruits, producing new poetic forms—and when it’s under strain as consensus emerges and chance intervenes to support some members but not others, and money and attention accumulate at a slower rate.

more here.

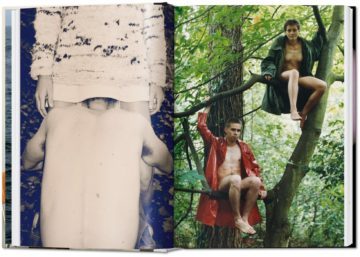

Wolfgang Tillmans Changed What Photos Look Like

Jerry Saltz at New York Magazine:

Over the course of his 36-year career, the photographer Wolfgang Tillmans has created what I think of as a new sublime. His work conveys that the bigness of it all is no longer in God, the ceilings of the Renaissance, the grandeur of nature, or the allover fields of the Abstract Expressionists. Tillmans intuited that the sublime had shifted, had alighted on us. It’s in an overhead shot of friends wearing camo and military garb sprawled on the beach in a frondlike configuration and cradling one another — becoming a single organism with tentacles. It’s in a man holding a naked woman’s legs apart and looking below her exposed bush to the grassy dunes beyond. The people we see are often Tillmans’s friends: artists, musicians, designers, dancers. But these aren’t the usual club-kid, gay-bar, grunge-life photos. The rhapsodic rapport Tillmans has with his subjects gives his work a tenderness that seems almost sacred.

Over the course of his 36-year career, the photographer Wolfgang Tillmans has created what I think of as a new sublime. His work conveys that the bigness of it all is no longer in God, the ceilings of the Renaissance, the grandeur of nature, or the allover fields of the Abstract Expressionists. Tillmans intuited that the sublime had shifted, had alighted on us. It’s in an overhead shot of friends wearing camo and military garb sprawled on the beach in a frondlike configuration and cradling one another — becoming a single organism with tentacles. It’s in a man holding a naked woman’s legs apart and looking below her exposed bush to the grassy dunes beyond. The people we see are often Tillmans’s friends: artists, musicians, designers, dancers. But these aren’t the usual club-kid, gay-bar, grunge-life photos. The rhapsodic rapport Tillmans has with his subjects gives his work a tenderness that seems almost sacred.

more here.

Lecture by Wolfgang Tillmans | Trafó Gallery

Mark Zuckerberg’s latest iteration of his virtual world has been derided as aesthetically primitive – but is that the point?

Justin E. H. Smith in The New Statesman:

In October 2021, Meta Platforms, Inc, released a “trailer”, hosted by the company’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg, to give a visual tour of its recent expansion into the Metaverse – the immersive, virtual-reality world that is expected to be the next great iteration of our internet technologies.

In October 2021, Meta Platforms, Inc, released a “trailer”, hosted by the company’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg, to give a visual tour of its recent expansion into the Metaverse – the immersive, virtual-reality world that is expected to be the next great iteration of our internet technologies.

It was a curious piece of work. The trailer began with Zuckerberg standing in a living room with a fireplace, a stunning mountain view, and other conventional signifiers of wealth. The Zuckerberg who first greets us appears to be the real one; he quickly proceeds to summon up a nearly life-size digital avatar of himself, and then runs through a sequence of possible costumes to dress his Meta-self in ahead of a virtual meeting with his Meta colleagues (or, more accurately, is yea-saying underlings). He briefly considers some more outlandish outfits before deciding on one that exactly matches what he, the real Zuckerberg, is already wearing: an unassuming anti-fashion ensemble for which he has long been known for, consisting of a black shirt and black trousers. This comedic set-up reveals something about the mentality behind the dismal aesthetics of the Metaverse as we have seen it so far.

More here.

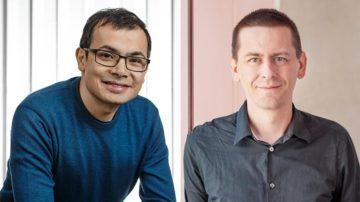

AlphaFold developers win US$3-million Breakthrough Prize

Zeeya Merali in Nature:

The researchers behind the AlphaFold artificial-intelligence (AI) system have won one of this year’s US$3-million Breakthrough prizes — the most lucrative awards in science. Demis Hassabis and John Jumper, both at DeepMind in London, were recognized for creating the tool that has predicted the 3D structures of almost every known protein on the planet.

The researchers behind the AlphaFold artificial-intelligence (AI) system have won one of this year’s US$3-million Breakthrough prizes — the most lucrative awards in science. Demis Hassabis and John Jumper, both at DeepMind in London, were recognized for creating the tool that has predicted the 3D structures of almost every known protein on the planet.

“Few discoveries so dramatically alter a field, so rapidly,” says Mohammed AlQuraishi, a computational biologist at Columbia University in New York City. “It’s really changed the practice of structural biology, both computational and experimental.”

The award was one of five Breakthrough prizes — awarded for achievements in life sciences, physics and mathematics — announced on 22 September.

More here.