Akin Adeṣọkan at The Current:

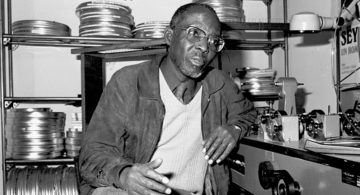

Birago Diop was a brilliant high-school student in Senegal. During his final exam, he made the unusual mistake of misconjugating a French verb, an error that was to prove fateful for his career. With a wry, self-deprecating smile past the camera, Diop, now an acclaimed poet and short-story writer, declares that what happened to him followed “the law of destiny.” The professional paths open to colonial students in the French system were narrow: they could become teachers if they passed a critical test, or doctors or civil servants if they didn’t. Diop went on to study veterinary medicine in France, and his collections are filled with animal tales.

Birago Diop was a brilliant high-school student in Senegal. During his final exam, he made the unusual mistake of misconjugating a French verb, an error that was to prove fateful for his career. With a wry, self-deprecating smile past the camera, Diop, now an acclaimed poet and short-story writer, declares that what happened to him followed “the law of destiny.” The professional paths open to colonial students in the French system were narrow: they could become teachers if they passed a critical test, or doctors or civil servants if they didn’t. Diop went on to study veterinary medicine in France, and his collections are filled with animal tales.

Sitting behind the camera and listening to this story in Birago Diop, conteur (1981), Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, the Beninese-Senegalese filmmaker, historian, critic, and bureaucrat, must have heard something of his own travails. The two men, both outstanding artists, achieved renown despite the constricting educational system of the French colonies.

more here.

The Plague was not an easy book to write. Camus was ill when he began it, then trapped by the borders keeping him in Nazi-occupied France. Aside from these difficulties, there was the pressure of authentically speaking up about the violence of World War II without falling into the nationalist heroics he deplored. Like with most problems in art, the solution was to address it directly: in one of the most revelatory sections of the novel, the character Tarrou blurs the line between fancy rhetoric and violence. “I’ve heard so much reasoning that almost turned my head,” he says, “and which had turned enough other heads to make them consent to killing, and I understood that all human sorrow came from not keeping language clear.”

The Plague was not an easy book to write. Camus was ill when he began it, then trapped by the borders keeping him in Nazi-occupied France. Aside from these difficulties, there was the pressure of authentically speaking up about the violence of World War II without falling into the nationalist heroics he deplored. Like with most problems in art, the solution was to address it directly: in one of the most revelatory sections of the novel, the character Tarrou blurs the line between fancy rhetoric and violence. “I’ve heard so much reasoning that almost turned my head,” he says, “and which had turned enough other heads to make them consent to killing, and I understood that all human sorrow came from not keeping language clear.” I

I Imagine you go to a zoology conference. The first speaker talks about her 3D model of a 12-legged purple spider that lives in the Arctic. There’s no evidence it exists, she admits, but it’s a testable hypothesis, and she argues that a mission should be sent off to search the Arctic for spiders.

Imagine you go to a zoology conference. The first speaker talks about her 3D model of a 12-legged purple spider that lives in the Arctic. There’s no evidence it exists, she admits, but it’s a testable hypothesis, and she argues that a mission should be sent off to search the Arctic for spiders. Parenting can make you wonder about human nature. If you have kids, you might have noticed their differences early on. When my infant son first heard music, his eyes grew big, and his gaze got intense. My infant daughter was clearly the people person. At 3 months, she was using her single tooth to mischievously bite me and watch my reaction. No wonder my son became a composer and my daughter turned to psychology.

Parenting can make you wonder about human nature. If you have kids, you might have noticed their differences early on. When my infant son first heard music, his eyes grew big, and his gaze got intense. My infant daughter was clearly the people person. At 3 months, she was using her single tooth to mischievously bite me and watch my reaction. No wonder my son became a composer and my daughter turned to psychology. The southwestern province of Balochistan and the southern province of Sindh have been the worst hit, with more than 500,000 people currently living in shelters. Across the country more than 750,000 livestock have died and over 3 million acres of agricultural land have been completely washed away. Agriculture accounts for more than a quarter of Pakistan’s economy. Of the country’s 154 districts, 116 are severely affected and 80 have been declared “calamity hit.”

The southwestern province of Balochistan and the southern province of Sindh have been the worst hit, with more than 500,000 people currently living in shelters. Across the country more than 750,000 livestock have died and over 3 million acres of agricultural land have been completely washed away. Agriculture accounts for more than a quarter of Pakistan’s economy. Of the country’s 154 districts, 116 are severely affected and 80 have been declared “calamity hit.” AT EVERY JOB

AT EVERY JOB T

T We have tried, in various ways, to convey to the world the scale of destruction caused by recent floods in Pakistan, because, apparently, a third of the country underwater and thirty-three million lives upended doesn’t cut it. Pakistan’s climate minister has called it Biblical. We have shot and shared videos in which the landmark New Honeymoon Hotel crumbles in the duration of a TikTok. The U.N. Secretary-General, António Guterres, who is seventy-three and has called the climate crisis a “

We have tried, in various ways, to convey to the world the scale of destruction caused by recent floods in Pakistan, because, apparently, a third of the country underwater and thirty-three million lives upended doesn’t cut it. Pakistan’s climate minister has called it Biblical. We have shot and shared videos in which the landmark New Honeymoon Hotel crumbles in the duration of a TikTok. The U.N. Secretary-General, António Guterres, who is seventy-three and has called the climate crisis a “ It was not an isolated incident of police violence in Iran. But the death of 22-year-old

It was not an isolated incident of police violence in Iran. But the death of 22-year-old  The word ‘bravery’ is applied all too liberally nowadays.

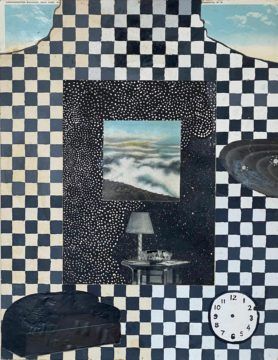

The word ‘bravery’ is applied all too liberally nowadays.  Ted and I saw one another off and on for about five years. In the spring of 1970, we lived together on Saint Mark’s Place in the East Village, until June, when Ted went to teach a course in Buffalo. I moved into the artists Rudy Burckhardt and Yvonne Jacquette’s loft on East Fourteenth Street while they summered in Maine. Ted stayed with me for a number of weekends that summer, and he proposed that we undertake a collaborative book. As I remember, I began the collaboration by making drawings with empty word balloons. I’m pretty sure Ted provided the project’s title at the outset. Ted would take the drawings—I think I made them in batches of four or five—back to Buffalo, where he began to fill in the words. We went back and forth this way, sometimes in person, sometimes by mail. I had forgotten all about this collaboration by the time Ted Berrigan’s youngest son, Eddie, contacted me in the summer of 2018. He wanted to bring me something his father and I had done together, which had recently turned up. As I looked at sixteen pages of my drawings and Ted’s handwritten words, the memories came back. These diaries describe some of them, along with the artistic milieu I was in in New York at that time—which included the painter Martha Diamond and the poets Bernadette Mayer, Michael Brownstein, Anne Waldman, and John Giorno.

Ted and I saw one another off and on for about five years. In the spring of 1970, we lived together on Saint Mark’s Place in the East Village, until June, when Ted went to teach a course in Buffalo. I moved into the artists Rudy Burckhardt and Yvonne Jacquette’s loft on East Fourteenth Street while they summered in Maine. Ted stayed with me for a number of weekends that summer, and he proposed that we undertake a collaborative book. As I remember, I began the collaboration by making drawings with empty word balloons. I’m pretty sure Ted provided the project’s title at the outset. Ted would take the drawings—I think I made them in batches of four or five—back to Buffalo, where he began to fill in the words. We went back and forth this way, sometimes in person, sometimes by mail. I had forgotten all about this collaboration by the time Ted Berrigan’s youngest son, Eddie, contacted me in the summer of 2018. He wanted to bring me something his father and I had done together, which had recently turned up. As I looked at sixteen pages of my drawings and Ted’s handwritten words, the memories came back. These diaries describe some of them, along with the artistic milieu I was in in New York at that time—which included the painter Martha Diamond and the poets Bernadette Mayer, Michael Brownstein, Anne Waldman, and John Giorno.