Andrew Keen in Literary Hub:

Did you know there are over 700 million government-owned surveillance cameras in China? I didn’t, until Liza Lin, The Wall Street Journal’s China correspondent, came on Keen On this week to talk about her new book Surveillance State. My intuitively Orwellian conclusion from this chilling statistic is that the Xi Jinping regime is creating a digital version of Ninety Eighty-Four, with government operated networked cameras on every street corner and in every bedroom, office, classroom and store.

Did you know there are over 700 million government-owned surveillance cameras in China? I didn’t, until Liza Lin, The Wall Street Journal’s China correspondent, came on Keen On this week to talk about her new book Surveillance State. My intuitively Orwellian conclusion from this chilling statistic is that the Xi Jinping regime is creating a digital version of Ninety Eighty-Four, with government operated networked cameras on every street corner and in every bedroom, office, classroom and store.

But Lin had another, weirdly counterintuitive explanation. The two largest manufacturers of surveillance cameras in the world are Chinese, she explained. And so China’s surveillance state, with its hundreds of millions of government-purchased cameras, is designed to benefit Chinese industry.

No wonder, then, that the Chinese state is now packaging this technology to the rest of the world. That may be all of our futures. State surveillance capitalism. Infinitely scalable. A win-win for both innovative entrepreneurs and dictators.

More here.

HAVING RESURFACED late in life due to a revival of her sex films, an eighty-nine-year-old Doris Wishman, clad in leopard print and wedge sandals, appeared on Late Night with Conan O’Brien in 2002. Conan is flummoxed by Wishman’s spiky retorts and willfully evasive manner. Affecting sheepishness when asked for the name of her latest (penultimate) film, she finally discloses the title: Dildo Heaven. Sensing discomfort, Wishman asks, “Conan, are you afraid of me?” The other guest, Roger Ebert, enters the fray to discuss Wishman’s work, announcing his familiarity with Deadly Weapons (1973) and Double Agent 73 (1974), which stars Chesty Morgan and her seventy-three-inch bustline. Ebert states that the only reason to watch these films, in his view, is to see Morgan entirely nude, and yet she remains mostly clothed. Wishman cannily replies: “Well Roger, I’m sorry you’re frustrated . . . Is there anything I can do?” Reframing male cinephilic desire as pitiful erotic disappointment, Wishman’s bait and switch is both the work of a cunning “exploiteer” in the old-school tradition, with some Borscht Belt thrown in, as well as a testament to the blurring of contraries she and her films embody: feigned prudery and ribald provocation, sincerity and self-consciousness. Asking Ebert why he didn’t put Dildo Heaven on his “Best Of” list, the filmmaker is met with the critic’s blanching reply—of course he likes to see films first before reviewing them! Wishman scoffs: “Ugh, how ordinary!”

HAVING RESURFACED late in life due to a revival of her sex films, an eighty-nine-year-old Doris Wishman, clad in leopard print and wedge sandals, appeared on Late Night with Conan O’Brien in 2002. Conan is flummoxed by Wishman’s spiky retorts and willfully evasive manner. Affecting sheepishness when asked for the name of her latest (penultimate) film, she finally discloses the title: Dildo Heaven. Sensing discomfort, Wishman asks, “Conan, are you afraid of me?” The other guest, Roger Ebert, enters the fray to discuss Wishman’s work, announcing his familiarity with Deadly Weapons (1973) and Double Agent 73 (1974), which stars Chesty Morgan and her seventy-three-inch bustline. Ebert states that the only reason to watch these films, in his view, is to see Morgan entirely nude, and yet she remains mostly clothed. Wishman cannily replies: “Well Roger, I’m sorry you’re frustrated . . . Is there anything I can do?” Reframing male cinephilic desire as pitiful erotic disappointment, Wishman’s bait and switch is both the work of a cunning “exploiteer” in the old-school tradition, with some Borscht Belt thrown in, as well as a testament to the blurring of contraries she and her films embody: feigned prudery and ribald provocation, sincerity and self-consciousness. Asking Ebert why he didn’t put Dildo Heaven on his “Best Of” list, the filmmaker is met with the critic’s blanching reply—of course he likes to see films first before reviewing them! Wishman scoffs: “Ugh, how ordinary!” Proprioception, the sense of where we are in space, can do more than simply bring character into focus—it also grants a kind of topicality when employed effectively. In the opening scene of Jesmyn Ward’s National Book Award-winning

Proprioception, the sense of where we are in space, can do more than simply bring character into focus—it also grants a kind of topicality when employed effectively. In the opening scene of Jesmyn Ward’s National Book Award-winning  The true horror of puberty isn’t the emergence of surprising hairs and baneful odors but the abrupt arrival of consequences. Physical ones, obviously — like the sudden possibility of getting pregnant or impregnating someone — but also existential consequences. To enter puberty is to discover not only that the stakes have ratcheted up, but that such a thing as “stakes” exist.

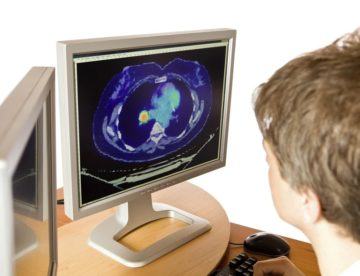

The true horror of puberty isn’t the emergence of surprising hairs and baneful odors but the abrupt arrival of consequences. Physical ones, obviously — like the sudden possibility of getting pregnant or impregnating someone — but also existential consequences. To enter puberty is to discover not only that the stakes have ratcheted up, but that such a thing as “stakes” exist. If a single medical objective could be applied to the entire range of cancers, it would be detecting the disease as soon as possible. “At the highest level, finding any cancer early gives you the opportunity for curative treatments,” says Andrea Ferris, CEO of research funding organization, LUNGevity. Although the goal of early detection emerged decades ago, much work remains to be done. Low-dose computed tomography (CT) scanning, used to detect lung cancer, has not changed much in the past ten years, and Ferris says that another part of the problem is a lack of public awareness of the “importance of screening and that it can save lives.”

If a single medical objective could be applied to the entire range of cancers, it would be detecting the disease as soon as possible. “At the highest level, finding any cancer early gives you the opportunity for curative treatments,” says Andrea Ferris, CEO of research funding organization, LUNGevity. Although the goal of early detection emerged decades ago, much work remains to be done. Low-dose computed tomography (CT) scanning, used to detect lung cancer, has not changed much in the past ten years, and Ferris says that another part of the problem is a lack of public awareness of the “importance of screening and that it can save lives.” In 1986, the US Fish and Wildlife Service took drastic, controversial action: they captured all remaining condors from the wild to save them.

In 1986, the US Fish and Wildlife Service took drastic, controversial action: they captured all remaining condors from the wild to save them. The detection of gravitational waves from inspiraling black holes by the LIGO and Virgo collaborations was rightly celebrated as a landmark achievement in physics and astronomy. But ultra-precise ground-based observatories aren’t the only way to detect gravitational waves; we can also search for their imprints on the timing of signals from pulsars scattered throughout our galaxy. Chiara Mingarelli is a member of the

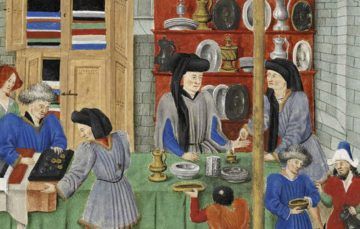

The detection of gravitational waves from inspiraling black holes by the LIGO and Virgo collaborations was rightly celebrated as a landmark achievement in physics and astronomy. But ultra-precise ground-based observatories aren’t the only way to detect gravitational waves; we can also search for their imprints on the timing of signals from pulsars scattered throughout our galaxy. Chiara Mingarelli is a member of the  In many ways, the story of medieval economic thought begins with the life of the founder of the Franciscan Order, Saint Francis of Assisi. He was born Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone in 1181 in Umbria, Italy, his father a silk merchant and his mother a noblewoman from Provence. The family was part of a new class of wealthy merchants who inhabited the Latin Mediterranean from Italy and southern France to Barcelona. It was a socioeconomic stratum that Francis would reject.

In many ways, the story of medieval economic thought begins with the life of the founder of the Franciscan Order, Saint Francis of Assisi. He was born Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone in 1181 in Umbria, Italy, his father a silk merchant and his mother a noblewoman from Provence. The family was part of a new class of wealthy merchants who inhabited the Latin Mediterranean from Italy and southern France to Barcelona. It was a socioeconomic stratum that Francis would reject. On the whole, motherhood has reshaped my life and habits in ways that have made me a lot happier, but the one thing I really miss from my childless life is waking up slowly. I have never been someone who jumps out of bed, eager to get started with my day. Instead, I like to lie in bed for a while to soak in the dream residue and listen to the radio and to the sounds coming from outside of my window. Maybe this is too obvious to say, but there is something uniquely relaxing about sleeping in after the sun has risen. Marcel Proust’s narrator, Marcel, a connoisseur of sleep, claims that morning sleep “is — on an average — four times as refreshing, it seems to the awakened sleeper to have lasted four times as long when it has really been four times as short. A splendid, sixteenfold error in multiplication which gives so much beauty to our awakening and gives life a veritable new dimension…”

On the whole, motherhood has reshaped my life and habits in ways that have made me a lot happier, but the one thing I really miss from my childless life is waking up slowly. I have never been someone who jumps out of bed, eager to get started with my day. Instead, I like to lie in bed for a while to soak in the dream residue and listen to the radio and to the sounds coming from outside of my window. Maybe this is too obvious to say, but there is something uniquely relaxing about sleeping in after the sun has risen. Marcel Proust’s narrator, Marcel, a connoisseur of sleep, claims that morning sleep “is — on an average — four times as refreshing, it seems to the awakened sleeper to have lasted four times as long when it has really been four times as short. A splendid, sixteenfold error in multiplication which gives so much beauty to our awakening and gives life a veritable new dimension…” Internal and external cues, such as

Internal and external cues, such as  Consider the many different purposes that can be served by conversation. Of course, we speak with others – and to ourselves! – to impart information. But we also exchange words to ask questions, forge connections, vent emotions, change attitudes, gain status, urge action, share stories, pass the time, advise, amuse, comfort, challenge, and much, much more. Examining what makes conversation work, and looking at how philosophers have thought about conversation, opens a window on to how language functions and how we function with language. So it is well to ask: what makes someone a good conversant? What makes conversation work?

Consider the many different purposes that can be served by conversation. Of course, we speak with others – and to ourselves! – to impart information. But we also exchange words to ask questions, forge connections, vent emotions, change attitudes, gain status, urge action, share stories, pass the time, advise, amuse, comfort, challenge, and much, much more. Examining what makes conversation work, and looking at how philosophers have thought about conversation, opens a window on to how language functions and how we function with language. So it is well to ask: what makes someone a good conversant? What makes conversation work? Six years ago, the psychologist Michael Inzlicht

Six years ago, the psychologist Michael Inzlicht  In the past, hosts like Johnny Carson and Jay Leno avoided taking partisan stances so they wouldn’t alienate half their viewers. Letterman and his successor, Conan O’Brien, did the same for the most part. In more recent years, journalists have discussed what is perceived as an increasing politicization and partisanship of late-night,

In the past, hosts like Johnny Carson and Jay Leno avoided taking partisan stances so they wouldn’t alienate half their viewers. Letterman and his successor, Conan O’Brien, did the same for the most part. In more recent years, journalists have discussed what is perceived as an increasing politicization and partisanship of late-night,