Steve Futterman at Commonweal:

For open-eared pop music fanatics of the seventies, Circle was a gateway album that revealed vistas. It spoke of a world beyond the sonic eruptions of rock-and-roll, yet one that could exist peaceably alongside it. The unassuming splendor of the music I heard that night in Central Park, particularly the marvelous flatpicking and straight-from-the-hills singing of Watson and the offhand brilliance of Scruggs’s banjo playing—indeed, the seemingly effortless, stirringly unselfconscious virtuosity of both men—brought to life the pleasures of a new idiom, one I still cherish. It was the joy already embedded in that momentous album come to life.

For open-eared pop music fanatics of the seventies, Circle was a gateway album that revealed vistas. It spoke of a world beyond the sonic eruptions of rock-and-roll, yet one that could exist peaceably alongside it. The unassuming splendor of the music I heard that night in Central Park, particularly the marvelous flatpicking and straight-from-the-hills singing of Watson and the offhand brilliance of Scruggs’s banjo playing—indeed, the seemingly effortless, stirringly unselfconscious virtuosity of both men—brought to life the pleasures of a new idiom, one I still cherish. It was the joy already embedded in that momentous album come to life.

Antecedents for the project were actually abundant. The Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, the Flying Burrito Brothers (with the stylistic pioneer Gram Parsons at the helm), the Band, the Grateful Dead, and, of course, Bob Dylan, among others, were already infusing elements of country and bluegrass into their sound.

more here.

In 1938, Joseph Roth sat across the street watching the demolition of the Paris hotel he called home. He drank, he smoked and he wrote a short, sharp, lyrical piece describing how, ‘because the hotel is shattered and the years I lived in it have gone, it seems bigger’. On the last remaining wall he could still see the blue and gold wallpaper of what had been his room. After it had been torn down, he drank and joked with ‘the destroyers’, until the significance of the moment hit him: ‘You lose one home after another … terror flutters up, and it doesn’t even frighten me any more. And that’s the most desolate thing of all.’ This is pure Roth, nostalgia vying with irony, gallows humour saving him from despair. Writing was for him a form of survival: ‘I can only understand the world when I’m writing, and the moment I put down my pen, I’m lost.’

In 1938, Joseph Roth sat across the street watching the demolition of the Paris hotel he called home. He drank, he smoked and he wrote a short, sharp, lyrical piece describing how, ‘because the hotel is shattered and the years I lived in it have gone, it seems bigger’. On the last remaining wall he could still see the blue and gold wallpaper of what had been his room. After it had been torn down, he drank and joked with ‘the destroyers’, until the significance of the moment hit him: ‘You lose one home after another … terror flutters up, and it doesn’t even frighten me any more. And that’s the most desolate thing of all.’ This is pure Roth, nostalgia vying with irony, gallows humour saving him from despair. Writing was for him a form of survival: ‘I can only understand the world when I’m writing, and the moment I put down my pen, I’m lost.’ Suketu Mehta

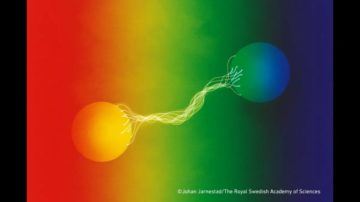

Suketu Mehta For generations, scientists argued over whether there was truly an objective, predictable reality for even quantum particles, or whether quantum “weirdness” was inherent to physical systems. In the 1960s, John Stewart Bell developed an inequality describing the maximum possible statistical correlation between two entangled particles: Bell’s inequality. But certain experiments could violate Bell’s inequality, and these three pioneers — John Clauser, Alain Aspect, and Anton Zeilinger — helped make quantum information systems a bona fide science.

For generations, scientists argued over whether there was truly an objective, predictable reality for even quantum particles, or whether quantum “weirdness” was inherent to physical systems. In the 1960s, John Stewart Bell developed an inequality describing the maximum possible statistical correlation between two entangled particles: Bell’s inequality. But certain experiments could violate Bell’s inequality, and these three pioneers — John Clauser, Alain Aspect, and Anton Zeilinger — helped make quantum information systems a bona fide science. Try to remember life as you lived it years ago, on a typical day in the fall. Back then, you cared deeply about certain things (a girlfriend? Depeche Mode?) but were oblivious of others (your political commitments? your children?). Certain key events—college? war? marriage? Alcoholics Anonymous?—hadn’t yet occurred. Does the self you remember feel like you, or like a stranger? Do you seem to be remembering yesterday, or reading a novel about a fictional character?

Try to remember life as you lived it years ago, on a typical day in the fall. Back then, you cared deeply about certain things (a girlfriend? Depeche Mode?) but were oblivious of others (your political commitments? your children?). Certain key events—college? war? marriage? Alcoholics Anonymous?—hadn’t yet occurred. Does the self you remember feel like you, or like a stranger? Do you seem to be remembering yesterday, or reading a novel about a fictional character? In a surprise discovery, researchers found that cells from some types of cancers escaped destruction by the immune system by hiding inside other cancer cells.

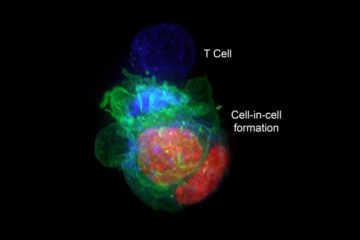

In a surprise discovery, researchers found that cells from some types of cancers escaped destruction by the immune system by hiding inside other cancer cells. Weiskrantz took a new approach with a human patient, known by the initials DB, who, after surgery to remove a growth affecting the visual cortex on the left side of his brain, was blind across the right-half field of vision. In the blind area, DB himself maintained that he had no visual awareness. Nonetheless, Weiskrantz asked him to guess the location and shape of an object that lay in this area. To everyone’s surprise, he consistently guessed correctly. To DB himself, his success in guessing seemed quite unreasonable. So far as he was concerned, he wasn’t the source of his perceptual judgments, his sight had nothing to do with him. Weiskrantz named this capacity ‘blindsight’: visual perception in the absence of any felt visual sensations.

Weiskrantz took a new approach with a human patient, known by the initials DB, who, after surgery to remove a growth affecting the visual cortex on the left side of his brain, was blind across the right-half field of vision. In the blind area, DB himself maintained that he had no visual awareness. Nonetheless, Weiskrantz asked him to guess the location and shape of an object that lay in this area. To everyone’s surprise, he consistently guessed correctly. To DB himself, his success in guessing seemed quite unreasonable. So far as he was concerned, he wasn’t the source of his perceptual judgments, his sight had nothing to do with him. Weiskrantz named this capacity ‘blindsight’: visual perception in the absence of any felt visual sensations.

Frans Hals was born in Antwerp in around 1582, moved to Haarlem when he was three, found fame rather late, in his mid-thirties, died in 1666 – and was forgotten, at least outside his native country. The apparent lack of finish in his work made it unfashionable in the eyes of connoisseurs and collectors until interest in his paintings grew again in the mid-19th century. In 1865 Hals’s Laughing Cavalier was bought for a vast sum by Lord Hertford and exhibited in London to huge acclaim. Soon afterwards it entered the Wallace Collection.

Frans Hals was born in Antwerp in around 1582, moved to Haarlem when he was three, found fame rather late, in his mid-thirties, died in 1666 – and was forgotten, at least outside his native country. The apparent lack of finish in his work made it unfashionable in the eyes of connoisseurs and collectors until interest in his paintings grew again in the mid-19th century. In 1865 Hals’s Laughing Cavalier was bought for a vast sum by Lord Hertford and exhibited in London to huge acclaim. Soon afterwards it entered the Wallace Collection. A team of computer scientists has come up with a

A team of computer scientists has come up with a  In September 2016 I gave a lecture at Duke University: “

In September 2016 I gave a lecture at Duke University: “ Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman, died on September 16th in Tehran after being detained and allegedly beaten by Iran’s

Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman, died on September 16th in Tehran after being detained and allegedly beaten by Iran’s  The first therapeutic cancer vaccine, approved more than a decade ago, targeted prostate tumours. The treatment involves extracting antigen-presenting cells — a component of the immune system that tells other cells what to target — from a person’s blood, loading them with a marker found on prostate tumours, and then returning them to the patient. The idea is that other immune cells will then take note and attack the cancer.

The first therapeutic cancer vaccine, approved more than a decade ago, targeted prostate tumours. The treatment involves extracting antigen-presenting cells — a component of the immune system that tells other cells what to target — from a person’s blood, loading them with a marker found on prostate tumours, and then returning them to the patient. The idea is that other immune cells will then take note and attack the cancer. The signaling behavior of human beings is intricate indeed. Forty years ago a man, seething with desire, issued forth a string of identical second-person singular imperatives followed by a hortatory first-person plural:

The signaling behavior of human beings is intricate indeed. Forty years ago a man, seething with desire, issued forth a string of identical second-person singular imperatives followed by a hortatory first-person plural: