Douglas Hofstadter in Inference Review:

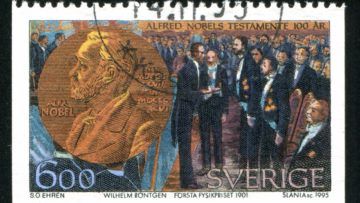

Actually, until 1961, when I was 16, I’d never given any thought to Sweden at all, but everything shifted on a dime when my Dad shared the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics. That December, our family flew to Stockholm for the ceremonies and it was unforgettable. Not only were the solemn, yet deeply joyous, festivities a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence, but I was powerfully struck by the classic European beauty of Stockholm in the midst of that romantically dark and snowy Scandinavian winter—such a clean and sophisticated city with its old-fashioned trams, its glittering neon signs, its colorful store windows, its elegant ladies and gentlemen, and, last but not least, its strange, alien language.

Actually, until 1961, when I was 16, I’d never given any thought to Sweden at all, but everything shifted on a dime when my Dad shared the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics. That December, our family flew to Stockholm for the ceremonies and it was unforgettable. Not only were the solemn, yet deeply joyous, festivities a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence, but I was powerfully struck by the classic European beauty of Stockholm in the midst of that romantically dark and snowy Scandinavian winter—such a clean and sophisticated city with its old-fashioned trams, its glittering neon signs, its colorful store windows, its elegant ladies and gentlemen, and, last but not least, its strange, alien language.

When, one day in the Grand Hôtel, which certainly lived up to its name, our family first laid eyes on my Dad’s Nobel diploma, colorfully and exquisitely hand-calligraphed in Swedish, I tried to make some sense of the citation—“För hans banbrytande undersökningar över elektronspridningen mot atomkärnor och därvid gjorda upptäckter rörande nuckleonernas struktur”—but I couldn’t do much with it. Although I knew a weensy bit of German, I didn’t know a word of any of its cousin languages, such as Swedish. And yet I instantly noticed something that looked odd; a tiny little thing that, to my eye, stuck out like a sore thumb. Even if you know zero Swedish, I urge you to try to spot the spot that was an eyesore to me. Hint: it’s just one word toward the end. And by the way, in English, what those italicized words mean is this: “For his pathbreaking investigations of electron-scattering from atomic nuclei, and for his discoveries, made thereby, concerning the structure of nucleons.”

More here.

WHEN I FINISHED MY FIRST READ of Which as You Know Means Violence, critic Philippa Snow’s debut “on self-injury as art and entertainment,” I returned to my own cultural hallmark of suffering, the 2006 film adaptation of The Da Vinci Code. Reading Snow’s analysis of artist Chris Burden’s 1974 crucifixion atop a Volkswagen Beetle alongside the comical stunts of Johnny Knoxville and his squad of Jackass pranksters, I thought frequently of Paul Bettany’s fanatical Silas, who torments himself to such extremes that he plays at the brink of absurdity. Silas spends most of his screen time scurrying around church cloisters in monk’s robes and a bloody cilice, or flagellating his back in penance, a commitment to suffering so all-consuming and ridiculous that, by his third murderous jump-scare, it’s a challenge not to laugh mid-flinch.

WHEN I FINISHED MY FIRST READ of Which as You Know Means Violence, critic Philippa Snow’s debut “on self-injury as art and entertainment,” I returned to my own cultural hallmark of suffering, the 2006 film adaptation of The Da Vinci Code. Reading Snow’s analysis of artist Chris Burden’s 1974 crucifixion atop a Volkswagen Beetle alongside the comical stunts of Johnny Knoxville and his squad of Jackass pranksters, I thought frequently of Paul Bettany’s fanatical Silas, who torments himself to such extremes that he plays at the brink of absurdity. Silas spends most of his screen time scurrying around church cloisters in monk’s robes and a bloody cilice, or flagellating his back in penance, a commitment to suffering so all-consuming and ridiculous that, by his third murderous jump-scare, it’s a challenge not to laugh mid-flinch. The Japanese writer Taeko Kōno is a maestro of transgressive desire whose stories often—and deliciously—use food as a metaphor for sexual appetite. Kōno, who died in 2015, is considered one of Japan’s foremost feminist writers and one of its foremost writers of any kind. She won many of the country’s top literary prizes, including the Akutagawa, the Tanizaki, the Noma, and the Yomiuri. The single selection of her work in English, Toddler-Hunting & Other Stories, first published by New Directions in 1996 and translated by Lucy North and Lucy Lower, contains ten dark, deceptively simple stories about women who find the gender roles in Japanese society unbearable, and are warped by them.

The Japanese writer Taeko Kōno is a maestro of transgressive desire whose stories often—and deliciously—use food as a metaphor for sexual appetite. Kōno, who died in 2015, is considered one of Japan’s foremost feminist writers and one of its foremost writers of any kind. She won many of the country’s top literary prizes, including the Akutagawa, the Tanizaki, the Noma, and the Yomiuri. The single selection of her work in English, Toddler-Hunting & Other Stories, first published by New Directions in 1996 and translated by Lucy North and Lucy Lower, contains ten dark, deceptively simple stories about women who find the gender roles in Japanese society unbearable, and are warped by them. In this essay, I argue for a reorientation of discourse about the humanities to the objects of humanistic study rather than claims for their value or effect. Returning to an essay Erwin Panofsky published in 1940, “The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline,” I build on Panofsky’s rich distinction between “monuments” and “documents” as the two sides of the humanistic object of study. By “monuments,” Panofsky refers to all of those human artifacts, actions, or ideas that have urgent meaning for us in the present. By “document,” he refers to all of those traces or records by means of which we recover monuments. Monuments and documents bring the long time of human existence, past or future, into relation to the short time of human life, a relation that defines the objects of study in all the humanities and confirms the undeniable interest of that study.

In this essay, I argue for a reorientation of discourse about the humanities to the objects of humanistic study rather than claims for their value or effect. Returning to an essay Erwin Panofsky published in 1940, “The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline,” I build on Panofsky’s rich distinction between “monuments” and “documents” as the two sides of the humanistic object of study. By “monuments,” Panofsky refers to all of those human artifacts, actions, or ideas that have urgent meaning for us in the present. By “document,” he refers to all of those traces or records by means of which we recover monuments. Monuments and documents bring the long time of human existence, past or future, into relation to the short time of human life, a relation that defines the objects of study in all the humanities and confirms the undeniable interest of that study.

Ben Bernanke at the Brookings Institution in Washington DC, Douglas Diamond at the University of Chicago in Illinois and Philip Dybvig at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, shared equal parts of the 10-million-Swedish-krona (US$915,000) award, formally known as the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.

Ben Bernanke at the Brookings Institution in Washington DC, Douglas Diamond at the University of Chicago in Illinois and Philip Dybvig at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, shared equal parts of the 10-million-Swedish-krona (US$915,000) award, formally known as the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. When the blackbird flew out of sight,

When the blackbird flew out of sight, Scientists have successfully transplanted clusters of human neurons into the brains of newborn rats, a striking feat of biological engineering that may provide more realistic models for neurological conditions such as autism and serve as a way to restore injured brains.

Scientists have successfully transplanted clusters of human neurons into the brains of newborn rats, a striking feat of biological engineering that may provide more realistic models for neurological conditions such as autism and serve as a way to restore injured brains. In the US, we are feeling the sickening after-effects of

In the US, we are feeling the sickening after-effects of  Actually, until 1961, when I was 16, I’d never given any thought to Sweden at all, but everything shifted on a dime when my Dad shared the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics. That December, our family flew to Stockholm for the ceremonies and it was unforgettable. Not only were the solemn, yet deeply joyous, festivities a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence, but I was powerfully struck by the classic European beauty of Stockholm in the midst of that romantically dark and snowy Scandinavian winter—such a clean and sophisticated city with its old-fashioned trams, its glittering neon signs, its colorful store windows, its elegant ladies and gentlemen, and, last but not least, its strange, alien language.

Actually, until 1961, when I was 16, I’d never given any thought to Sweden at all, but everything shifted on a dime when my Dad shared the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics. That December, our family flew to Stockholm for the ceremonies and it was unforgettable. Not only were the solemn, yet deeply joyous, festivities a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence, but I was powerfully struck by the classic European beauty of Stockholm in the midst of that romantically dark and snowy Scandinavian winter—such a clean and sophisticated city with its old-fashioned trams, its glittering neon signs, its colorful store windows, its elegant ladies and gentlemen, and, last but not least, its strange, alien language. In 1977, Ken Olsen declared that ‘there is no reason for any individual to have a computer in his home.’ In 1995, Robert Metcalfe predicted in InfoWorld that the internet would go ‘spectacularly supernova’ and then collapse within a year. In 2000, the Daily Mail reported that the ‘Internet may be just a passing fad,’ adding that ‘predictions that the Internet would revolutionise the way society works have proved wildly inaccurate.’ Any day now, the millions of internet users would simply stop, either bored or frustrated, and rejoin the real world.

In 1977, Ken Olsen declared that ‘there is no reason for any individual to have a computer in his home.’ In 1995, Robert Metcalfe predicted in InfoWorld that the internet would go ‘spectacularly supernova’ and then collapse within a year. In 2000, the Daily Mail reported that the ‘Internet may be just a passing fad,’ adding that ‘predictions that the Internet would revolutionise the way society works have proved wildly inaccurate.’ Any day now, the millions of internet users would simply stop, either bored or frustrated, and rejoin the real world. Nobel Prizes used to be awarded fairly quickly after the discovery, achievement, or event that prompted them. The instructions left by Alfred Nobel seemed to warrant this speed. However, this has occasionally led to awards for discoveries that later turned out to be bunk. Perhaps no case of this is clearer-cut than the 1926 prize in medicine, which was awarded “for [Fibiger’s] discovery of the Spiroptera carcinoma.”

Nobel Prizes used to be awarded fairly quickly after the discovery, achievement, or event that prompted them. The instructions left by Alfred Nobel seemed to warrant this speed. However, this has occasionally led to awards for discoveries that later turned out to be bunk. Perhaps no case of this is clearer-cut than the 1926 prize in medicine, which was awarded “for [Fibiger’s] discovery of the Spiroptera carcinoma.” The House committee tasked with investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol made its closing arguments to the American public today and voted 9-0 to subpoena former President Donald Trump. They highlighted snippets from more than a million Secret Service communications in the days and hours leading up to the breach of the Capitol, bolstering their thesis that then-President Donald Trump had incited a mob and bears singular responsibility for the violence that ensued. “Armed and Ready, Mr. President!” read one snippet of intelligence presented in a Secret Service email on Dec. 24, 2020, about two weeks before the Jan. 6 joint session of Congress to formalize Joe Biden’s election victory.

The House committee tasked with investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol made its closing arguments to the American public today and voted 9-0 to subpoena former President Donald Trump. They highlighted snippets from more than a million Secret Service communications in the days and hours leading up to the breach of the Capitol, bolstering their thesis that then-President Donald Trump had incited a mob and bears singular responsibility for the violence that ensued. “Armed and Ready, Mr. President!” read one snippet of intelligence presented in a Secret Service email on Dec. 24, 2020, about two weeks before the Jan. 6 joint session of Congress to formalize Joe Biden’s election victory. Pain has been long recognized as one of evolution’s most reliable tools to detect the presence of harm and signal that something is wrong—an alert system that tells us to pause and pay attention to our bodies. But what if

Pain has been long recognized as one of evolution’s most reliable tools to detect the presence of harm and signal that something is wrong—an alert system that tells us to pause and pay attention to our bodies. But what if