Category: Recommended Reading

How the Victorians Took Us to the Moon

Katy Guest at The Guardian:

As he unveiled Tesla’s new humanoid robot, Optimus, this September, Elon Musk spoke with characteristic flamboyance about the device’s potential. “This means a future of abundance,” he declared. “A future where there is no poverty … It really is a fundamental transformation of civilisation as we know it.” Perhaps deliberately, he was echoing the tone of his company’s namesake, Nikola Tesla, who in the 1890s was making similarly bold claims about his own work-in-progress. With his new system of wireless telegraphy, Tesla insisted, battleships would be controlled remotely, meaning that pretty soon “war would be abolished” and there would be a “revolution in the politics of the whole world”.

As he unveiled Tesla’s new humanoid robot, Optimus, this September, Elon Musk spoke with characteristic flamboyance about the device’s potential. “This means a future of abundance,” he declared. “A future where there is no poverty … It really is a fundamental transformation of civilisation as we know it.” Perhaps deliberately, he was echoing the tone of his company’s namesake, Nikola Tesla, who in the 1890s was making similarly bold claims about his own work-in-progress. With his new system of wireless telegraphy, Tesla insisted, battleships would be controlled remotely, meaning that pretty soon “war would be abolished” and there would be a “revolution in the politics of the whole world”.

How the Victorians Took Us to the Moon argues that this triumphalist view of the future, so much the norm among Tesla’s contemporaries, led directly to the advances that enabled the moon landings, the technological present we now inhabit and the way we still think about the future today.

more here.

What Next For Detroit?

Thomas J. Sugrue at Public Books:

Vergara’s newest book, Detroit Is No Dry Bones, powerfully documents the transformation of Detroit over the last several decades, offering an unflinching portrayal of a city gutted by decades of anti-urban public policies, intense racial segregation, and heartlessly mobile capital. Vergara’s approach is a reminder of the power of looking at small things—a fence, a broken window, a graffiti-strewn brick wall, a lawn ornament—to illustrate what might otherwise be impersonal processes and grand social forces. But Vergara’s keen eye also sees what cannot simply be reduced to urban decay. A raggedy lot becomes a lush garden, a blank wall becomes a canvas for an unknown artist, a pile of tires and a piece of wood become an impromptu bench at a bus stop. Vergara’s Detroit is not simply an acropolis, it is a place of rebirth and reinvention.

Vergara’s newest book, Detroit Is No Dry Bones, powerfully documents the transformation of Detroit over the last several decades, offering an unflinching portrayal of a city gutted by decades of anti-urban public policies, intense racial segregation, and heartlessly mobile capital. Vergara’s approach is a reminder of the power of looking at small things—a fence, a broken window, a graffiti-strewn brick wall, a lawn ornament—to illustrate what might otherwise be impersonal processes and grand social forces. But Vergara’s keen eye also sees what cannot simply be reduced to urban decay. A raggedy lot becomes a lush garden, a blank wall becomes a canvas for an unknown artist, a pile of tires and a piece of wood become an impromptu bench at a bus stop. Vergara’s Detroit is not simply an acropolis, it is a place of rebirth and reinvention.

more here.

Nā́rī

Magali Nuzant in lensculture:

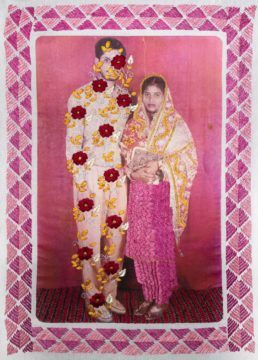

The images are printed on khadi, the cloth produced by traditional spinning wheels—the charkha, a device that is deeply rooted in Indian history. During the struggle for independence, Mahatma Gandhi used the spinning wheel as a symbol of self-reliance, urging Indians to spin their own cloth as a means of gaining economic freedom from the exploitation of British colonizers. If the spinning wheel has come to be a symbol of self-reliance, then in the work of Malik, the act of embroidery embodies resistance and the strength and care that can be found in community. Behind the work lies the reality of the struggle for women’s rights and the issue of gendered violence in India.

The images are printed on khadi, the cloth produced by traditional spinning wheels—the charkha, a device that is deeply rooted in Indian history. During the struggle for independence, Mahatma Gandhi used the spinning wheel as a symbol of self-reliance, urging Indians to spin their own cloth as a means of gaining economic freedom from the exploitation of British colonizers. If the spinning wheel has come to be a symbol of self-reliance, then in the work of Malik, the act of embroidery embodies resistance and the strength and care that can be found in community. Behind the work lies the reality of the struggle for women’s rights and the issue of gendered violence in India.

“‘Nā́rī’ is a word that I’ve used all my life,” explains Malik. “There are multiple definitions that appear in Hindi: woman, wife, female, an object that is regarded as feminine, but it also means sacrifice. When I first read that, I started to read more about women in the time that the word was coined and all that women had to sacrifice throughout history, all the rituals that were part of the culture, that were built around this word.”

More here.

The Kingdom of Antonin Scalia

Liza Batkin in The New Yorker:

In 1978, when Antonin Scalia was still a law professor at the University of Chicago, the American Enterprise Institute invited him to a panel called “An Imperial Judiciary: Fact or Myth?” On his side of the table was Laurence Silberman, who had been Richard Nixon’s Deputy Attorney General; across from them sat the executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union and a Harvard Law professor. Within the previous several years, the Supreme Court had established the right to abortion and had upheld a lower court ruling that required schools to bus students from other districts as a remedy for segregation. The panel’s speakers were debating whether the judiciary had taken on an outsized role in public life and the political process.

In 1978, when Antonin Scalia was still a law professor at the University of Chicago, the American Enterprise Institute invited him to a panel called “An Imperial Judiciary: Fact or Myth?” On his side of the table was Laurence Silberman, who had been Richard Nixon’s Deputy Attorney General; across from them sat the executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union and a Harvard Law professor. Within the previous several years, the Supreme Court had established the right to abortion and had upheld a lower court ruling that required schools to bus students from other districts as a remedy for segregation. The panel’s speakers were debating whether the judiciary had taken on an outsized role in public life and the political process.

“I am not particularly concerned about whether the courts put the crown on their own head in Napoleonic fashion or whether somebody else conferred it upon them,” Scalia said to the panel. “We can blame everybody: the Congress, the executive, and the courts. I do not care whom we blame, I just do not want the crown there.” The philosophy that he went on to develop as a professor and Justice took aim at broad, ambiguous, and flexible decrees that he thought let judges rule imperiously.

More here.

Saturday Poem

A Little Flower

A little flower doesn’t know how beautiful she is

She has no such a concept

A little flower doesn’t even know her own name

Not to mention the meaning

On the side of the road

A little flower never feels lonely

She blooms as if she doesn’t know she will wither

She withers as if she doesn’t know what is wither

She just quietly blooms, blooms

Like a ring that is just the right size

Worn on the knuckle of God

by Ting Li

from Rattle #77, Fall 2022

Translated from the Chinese by the author

Friday, November 11, 2022

Beauty and Truth Again? Lessons from Physics, Art, and Theology

Tom McLeish at Marginalia:

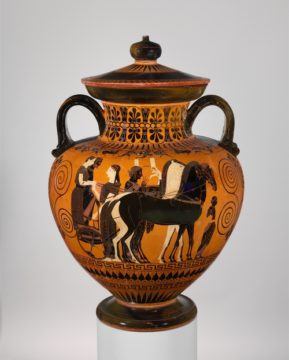

There are distinct signs that the poet John Keats’ Grecian Urn has found its voice again. This is a surprise. The final Delphic utterance of the decorated vessel in his poem Ode to a Grecian Urn runs: “Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty, — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” Though well-known as verse, it has long been relegated to romantic wishful thinking.

There are distinct signs that the poet John Keats’ Grecian Urn has found its voice again. This is a surprise. The final Delphic utterance of the decorated vessel in his poem Ode to a Grecian Urn runs: “Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty, — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” Though well-known as verse, it has long been relegated to romantic wishful thinking.

The dominant, highly dualistic discussion of beauty and truth over the last century, and of aesthetics more generally, has long stifled the wistful notion that beautiful ideas are more likely to be true than ugly ones. Furthermore, multiple voices in late modern philosophy adopt the equally dualistic assurance that the objective (truth) and subjective (beauty) simply don’t mix, that they support no connection, enjoy no conversation. Yet a recently-published and extensive survey of over 20,000 scientists in the US, India, Italy and the UK, The Role of Aesthetics in Science, by Brandon Vaidyanathan and Christopher Jacobi, found that only 34% of scientists disagreed with the statement declaring “mathematical beauty is a good indicator of scientific truth.” A very large majority also found that the objects of their scientific investigations were aesthetically beautiful.

Here, I want to explore the reasons for the apparent failure to suffocate the Urn’s continuing voice in our own time. Anticipating that this will require some philosophy as well as the testimony of science itself, the continually conflictual conversations between beauty and truth will require listening to the arts, as well as the sciences. Surprisingly perhaps, the road to resolution leads through theology.

More here.

AI uses artificial sleep to learn new task without forgetting the last

Jeremy Hsu in New Scientist:

Artificial intelligence can learn and remember how to do multiple tasks by mimicking the way sleep helps us cement what we learned during waking hours.

Artificial intelligence can learn and remember how to do multiple tasks by mimicking the way sleep helps us cement what we learned during waking hours.

“There is a huge trend now to bring ideas from neuroscience and biology to improve existing machine learning – and sleep is one of them” says Maxim Bazhenov at the University of California, San Diego.

Many AIs can only master one set of well-defined tasks – they can’t acquire additional knowledge later on without losing everything they had previously learned. “The issue pops up if you want to develop systems which are capable of so-called lifelong learning,” says Pavel Sanda at the Czech Academy of Sciences in the Czech Republic. Lifelong learning is how humans accumulate knowledge to adapt to and solve future challenges.

Bazhenov, Sanda and their colleagues trained a spiking neural network – a connected grid of artificial neurons resembling the human brain’s structure – to learn two different tasks without overwriting connections learned from the first task. They accomplished this by interspersing focused training periods with sleep-like periods.

More here.

World Orchestra for Peace – Valery Gergiev: Mahler Symphony No.5, 4th Movement “Adagietto”

Lunchtime in Italy: On solidarity in civic life

Jonathan Levy in the Boston Review:

The morning after the 2016 U.S. presidential election, my partner Skyped her parents back home in Italy. I finished my coffee, and they chatted. At some point her mother asked where I was: I had broken my usual pattern of dropping in to say ciao. My partner slid the laptop over to direct the camera’s gaze at my head, slumped onto our dining room table. “What happened?” the voice on the computer asked. “Trump won,” I explained.

The morning after the 2016 U.S. presidential election, my partner Skyped her parents back home in Italy. I finished my coffee, and they chatted. At some point her mother asked where I was: I had broken my usual pattern of dropping in to say ciao. My partner slid the laptop over to direct the camera’s gaze at my head, slumped onto our dining room table. “What happened?” the voice on the computer asked. “Trump won,” I explained.

It is not that my in-laws did not appreciate the gravity of the event; they were stunned too. Born under Mussolini, they preferred to look fondly upon the United States whenever possible. After all, the U.S. Army helped liberate their country from fascism. Like many outside the United States, and unlike many Americans, they appreciate the power the U.S. government enjoys abroad. After sharing in the dour mood, to console me, my mother-in-law asked, “Well . . . what is there for lunch?”

The question was a nudge back from the brink of political despair. But many questions could have accomplished that end. She asked about lunchtime. Having been visiting Italy regularly for over a decade, I could understand why.

More here.

Giorgio Agamben. The Archaeology of Commandment.

The Mark Fisher Generation

Alex Niven at The New Statesman:

For me, and for many others, encountering Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism in 2009 felt like coming up for air. In a society where everything was arranged to make you think that emotional well-being began and ended with your own personal psychodrama, perhaps the most important thing Capitalist Realism did was to suggest that mental suffering might have something to do with structural flaws in society as a whole. In a political system which endlessly promoted the notion that we were all alone, Fisher’s book announced that we were suffering together. Also, more hopefully, it said that if we were to realise this, and somehow make connections between our several hardships, we would be taking the first step towards doing something we seemed to have mostly forgotten about by the late Noughties: mounting an organised resistance. This is the near-spiritual message in the short, sharp text of Capitalist Realism, published on the eve of a new and tumultuous decade. Whatever political and theoretical nuances it might otherwise have implied, this was a book which called for a joining of human hands.

For me, and for many others, encountering Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism in 2009 felt like coming up for air. In a society where everything was arranged to make you think that emotional well-being began and ended with your own personal psychodrama, perhaps the most important thing Capitalist Realism did was to suggest that mental suffering might have something to do with structural flaws in society as a whole. In a political system which endlessly promoted the notion that we were all alone, Fisher’s book announced that we were suffering together. Also, more hopefully, it said that if we were to realise this, and somehow make connections between our several hardships, we would be taking the first step towards doing something we seemed to have mostly forgotten about by the late Noughties: mounting an organised resistance. This is the near-spiritual message in the short, sharp text of Capitalist Realism, published on the eve of a new and tumultuous decade. Whatever political and theoretical nuances it might otherwise have implied, this was a book which called for a joining of human hands.

more here.

The Singularities By John Banville

Ian Critchley at Literary Review:

John Banville once told an interviewer that he absolutely hates being John Banville. He was contrasting his productivity as a literary novelist with his achievements writing crime fiction under the name Benjamin Black. ‘On a good day,’ he said, ‘Banville can’t write more than four hundred words … With Black it’s ten times more.’ Banville’s literary novels may be painstaking to write, but the results are usually worth it. Full of exquisite prose, humour and stunning flights of fancy, they have secured his reputation as one of the best stylists of his generation.

John Banville once told an interviewer that he absolutely hates being John Banville. He was contrasting his productivity as a literary novelist with his achievements writing crime fiction under the name Benjamin Black. ‘On a good day,’ he said, ‘Banville can’t write more than four hundred words … With Black it’s ten times more.’ Banville’s literary novels may be painstaking to write, but the results are usually worth it. Full of exquisite prose, humour and stunning flights of fancy, they have secured his reputation as one of the best stylists of his generation.

His new novel returns to Arden House, a crumbling old pile that was the setting of 2009’s The Infinities. In that earlier novel, scientist and ‘thoroughgoing shit’ Adam Godley was nearing the end of his life; The Singularities picks up the story several years later.

more here.

Return of Nutkin: Red squirrels’ comeback in UK

Jason Thomson in The Christian Science Monitor:

As I stand on the blue bridge, gateway to a subtropical garden on this island haven near southwestern England, I look to the side and see a small creature sitting astride a mound of hazelnuts. Its fur blazes a bright russet color, its tail fanned out like a sail. I glance up, and in the neighboring pine tree I see two or three more, racing up and down the trunk, pausing every so often to steal a glance at the feast below, waiting their turn. These are red squirrels, and to see them in the wild, let alone in such numbers, is a rare treat. The animals were once common throughout the United Kingdom, but the invasive gray squirrel has pushed them to the brink of extinction in all but a few strongholds.

As I stand on the blue bridge, gateway to a subtropical garden on this island haven near southwestern England, I look to the side and see a small creature sitting astride a mound of hazelnuts. Its fur blazes a bright russet color, its tail fanned out like a sail. I glance up, and in the neighboring pine tree I see two or three more, racing up and down the trunk, pausing every so often to steal a glance at the feast below, waiting their turn. These are red squirrels, and to see them in the wild, let alone in such numbers, is a rare treat. The animals were once common throughout the United Kingdom, but the invasive gray squirrel has pushed them to the brink of extinction in all but a few strongholds.

…Red squirrels have been a part of Britain’s native fauna for thousands of years. They are emblematic of the British countryside, so much so that generations of schoolchildren have been raised on Beatrix Potter’s “tale of a tail” about a little red squirrel named Nutkin. By contrast, the first recorded introduction of North American gray squirrels into a British park occurred in the 1870s.

More here.

100 years after his birth, Kurt Vonnegut is more relevant than ever to science

Zack Savitsky in Science:

When American novelist Kurt Vonnegut addressed the Bennington College class of 1970—1 year after publishing his best-selling novel, Slaughterhouse-Five—he hit the crowd with his signature one-two punch. “I fully expected that by the time I was 21, some scientist … would have taken a color photograph of God Almighty and sold it to Popular Mechanics magazine,” he said. “What actually happened … was that we dropped scientific truth on Hiroshima.” This weary skepticism for the scientific endeavor rings through many of Vonnegut’s 14 novels and dozens of short stories. For what would have been the famed author’s 100th birthday, Science talked to literary scholars, philosophers of science, and political theorists about the messages Vonnegut left for the scientific community—and why he’s more relevant than ever.

When American novelist Kurt Vonnegut addressed the Bennington College class of 1970—1 year after publishing his best-selling novel, Slaughterhouse-Five—he hit the crowd with his signature one-two punch. “I fully expected that by the time I was 21, some scientist … would have taken a color photograph of God Almighty and sold it to Popular Mechanics magazine,” he said. “What actually happened … was that we dropped scientific truth on Hiroshima.” This weary skepticism for the scientific endeavor rings through many of Vonnegut’s 14 novels and dozens of short stories. For what would have been the famed author’s 100th birthday, Science talked to literary scholars, philosophers of science, and political theorists about the messages Vonnegut left for the scientific community—and why he’s more relevant than ever.

More here.

Friday Poem

Abuela Warns Me a Caravan Of “Esa Gente” Is Headed Our Way

—After Lucille Clifton

if i should

take you

to that spot

by the water

you can’t pronounce

but love

because it reminds you

of Varadero

the fabled Cuban beach

you confessed

to having seen

only once

because the bus ride

from el campo

cost tres pesetas

too many

and as the oldest

of five siblings

you could not

leave the little ones

behind, you

so young

but already adept

at the doing without

of mothering

if i should

despite knowing

this about you

refuse to translate

the menu for you

refuse to place

your order

in English for you

if i should

stiff the blonde waiter

who does not deign

to acknowledge you

of his tip

if i should

ask it of you

then

would you

finally say

esa gente

son mi gente

esa gente

soy yo.*

by Caridad Moro-Gronlier

from Split This Rock

*

those people

They are my people

those people

This is me.

Thursday, November 10, 2022

Understanding liberalism as a culture not just a tidy set of axioms

Charles Mathewes in The Hedgehog Review:

Francis Fukuyama’s work is generally treated much the way pigeons treat statues: as something on which to deposit badly digested ideas, which are then left for others to clean up. His notoriety for the “End of History” thesis is based on a misreading of that phrase, not a real reading of his 1989 National Interest article “The End of History?” or his less sanguine 1992 book The End of History and the Last Man. His subsequent work has received respectful public attention, but little scholarly engagement; he is treated more as a symptom than an intellect. Even with this book, the pattern of neglect-by-vague-praise continues: None of its many reviewers, for all their pretense at comprehension, noticed that his drive-by definition of “deontology” (“not linked to any ontology or substantive theory of human nature”) is totally wrong: Deontology comes from deon, a Greek word here meaning something like “duty” and refers to the study of ethics.

Francis Fukuyama’s work is generally treated much the way pigeons treat statues: as something on which to deposit badly digested ideas, which are then left for others to clean up. His notoriety for the “End of History” thesis is based on a misreading of that phrase, not a real reading of his 1989 National Interest article “The End of History?” or his less sanguine 1992 book The End of History and the Last Man. His subsequent work has received respectful public attention, but little scholarly engagement; he is treated more as a symptom than an intellect. Even with this book, the pattern of neglect-by-vague-praise continues: None of its many reviewers, for all their pretense at comprehension, noticed that his drive-by definition of “deontology” (“not linked to any ontology or substantive theory of human nature”) is totally wrong: Deontology comes from deon, a Greek word here meaning something like “duty” and refers to the study of ethics.

The slip-up is a little embarrassing, but it doesn’t really damage the book’s argument.

More here.

Sex, Gender, and Cancel Culture on Campus

Paper by Carole K. Hooven:

I teach in and co-direct the undergraduate program in the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University. During the promotion of my recent book on testosterone and sex differences, I appeared on “Fox and Friends,” a Fox News program, and explained that sex is binary and biological. In response, the director of my department’s Diversity, Inclusion and Belonging task force (a graduate student) accused me on Twitter of transphobia and harming undergraduates, and I responded. The tweets went viral, receiving international news coverage. The public attack by the task force director runs contrary to Harvard’s stated academic freedom principles, yet no disciplinary action was taken, nor did any university administrators publicly support my right to express my views in an environment free of harassment. Unfortunately, what happened to me is not unusual, and an increasing number of scholars face restrictions imposed by formal sanctions or the creation of hostile work environments. In this article, I describe what happened to me, discuss why clear talk about the science of sex and gender is increasingly met with hostility on college campuses, why administrators are largely failing in their responsibilities to protect scholars and their rights to express their views, and what we can do to remedy the situation.

I teach in and co-direct the undergraduate program in the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University. During the promotion of my recent book on testosterone and sex differences, I appeared on “Fox and Friends,” a Fox News program, and explained that sex is binary and biological. In response, the director of my department’s Diversity, Inclusion and Belonging task force (a graduate student) accused me on Twitter of transphobia and harming undergraduates, and I responded. The tweets went viral, receiving international news coverage. The public attack by the task force director runs contrary to Harvard’s stated academic freedom principles, yet no disciplinary action was taken, nor did any university administrators publicly support my right to express my views in an environment free of harassment. Unfortunately, what happened to me is not unusual, and an increasing number of scholars face restrictions imposed by formal sanctions or the creation of hostile work environments. In this article, I describe what happened to me, discuss why clear talk about the science of sex and gender is increasingly met with hostility on college campuses, why administrators are largely failing in their responsibilities to protect scholars and their rights to express their views, and what we can do to remedy the situation.

More here.

Soumahoro: The migrant who can save the Italian left

Santiago Zabala at Al Jazeera:

With the centre-left divided and in perpetual crisis, none of its well-known leaders appears remotely capable of forming an effective opposition movement against the far-right government.

With the centre-left divided and in perpetual crisis, none of its well-known leaders appears remotely capable of forming an effective opposition movement against the far-right government.

There is, however, one progressive in the new Italian parliament who has a real chance of reviving the long-flailing Italian left and forming an opposition movement that can actually pose a meaningful challenge to Meloni: migrant union leader Aboubakar Soumahoro.

Soumahoro, 42, is an Ivory Coast native who migrated to Italy in 1999, aged 19, with the dream of building a better life in the country. After sleeping rough on the streets of Rome for some time, he eventually managed to overcome the many obstacles to migrant success in Italy, became an Italian citizen and completed a degree in sociology at the University of Naples.

More here.