Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

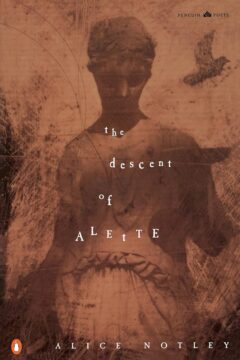

Remembering Alice Notley

Nick Sturm at Poetry Magazine:

A few days before she died, I asked Alice if she would make me a list of her favorite folk songs, the ones she’d sometimes sing while we worked together in her apartment. She emailed me from her hospital bed with the subject line “probably illegible” and a photo showing her open notebook with two pages of handwritten song titles. “Careless Love,” “Wild Mountain Thyme,” “What is the Soul of a Man,” “Shady Grove.” At the bottom of the image, she arranged two figurines—a blue-eyed owl and little R2-D2—to weigh down the pages. “Baby, Please Don’t Go,” “Down in the Valley,” “Spanish Johnny,” “In the Pines.” There are no musicians, just song titles—these are folk and blues songs, after all—all written in her lush cursive. “Shenandoah,” “Black Is the Color of My True Love’s Hair,” “The Water Is Wide,” “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean.” This will be the last thing she says to me.

A few days before she died, I asked Alice if she would make me a list of her favorite folk songs, the ones she’d sometimes sing while we worked together in her apartment. She emailed me from her hospital bed with the subject line “probably illegible” and a photo showing her open notebook with two pages of handwritten song titles. “Careless Love,” “Wild Mountain Thyme,” “What is the Soul of a Man,” “Shady Grove.” At the bottom of the image, she arranged two figurines—a blue-eyed owl and little R2-D2—to weigh down the pages. “Baby, Please Don’t Go,” “Down in the Valley,” “Spanish Johnny,” “In the Pines.” There are no musicians, just song titles—these are folk and blues songs, after all—all written in her lush cursive. “Shenandoah,” “Black Is the Color of My True Love’s Hair,” “The Water Is Wide,” “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean.” This will be the last thing she says to me.

I adored Alice. Writing that sentence is bright pain. I adore her.

The last time I saw Alice earlier this year, I was in Paris for a week to pack her archive. Everything we had sorted through and inventoried during my previous visits we touched again, together, before placing it all in newly labeled folders and boxes.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Zhuangzi And The Butterfly Self

Alexander Douglas at Aeon Magazine:

Zhuangzi’s view, as interpreted by Guo, is that when we seek a definite identity, we betray our true nature as fundamentally fluid and indeterminate. We end up pursuing some external model of definiteness. Even if the model is one of our own devising, it is external to our true indefinite nature. One story in the Zhuangzi tells of a welcoming and benevolent but faceless emperor, Hundun. Hundun has a face drilled into him by two other emperors who already have faces of their own. As a result, he dies. The story suggests that fixed identity always comes to us from the outside, from others who have already attached themselves to fixed identities and drive us to do the same, not usually by drills but rather by example. This peer-driven attachment to identity kills our fundamental nature, which is formless and fluid like Hundun (his name, 混沌, means something like ‘mixed-up chaos’, and each character contains the water radical signalling fluidity). Our true Hundun-nature is the capacity to take on many forms without being finally defined by any of them.

Zhuangzi’s view, as interpreted by Guo, is that when we seek a definite identity, we betray our true nature as fundamentally fluid and indeterminate. We end up pursuing some external model of definiteness. Even if the model is one of our own devising, it is external to our true indefinite nature. One story in the Zhuangzi tells of a welcoming and benevolent but faceless emperor, Hundun. Hundun has a face drilled into him by two other emperors who already have faces of their own. As a result, he dies. The story suggests that fixed identity always comes to us from the outside, from others who have already attached themselves to fixed identities and drive us to do the same, not usually by drills but rather by example. This peer-driven attachment to identity kills our fundamental nature, which is formless and fluid like Hundun (his name, 混沌, means something like ‘mixed-up chaos’, and each character contains the water radical signalling fluidity). Our true Hundun-nature is the capacity to take on many forms without being finally defined by any of them.

This encounter with a distant philosophical culture liberates us to ask questions we might not have otherwise thought to ask. Imagine if we hadn’t been conditioned to believe that our true self is something fixed and inborn.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

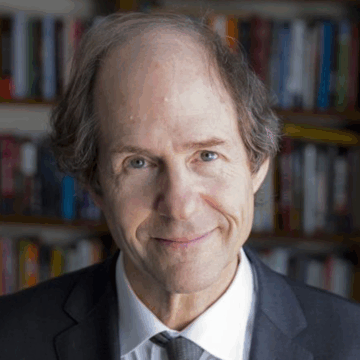

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Cass Sunstein on Liberalism

Sean Carroll at Preposterous Universe:

“Liberalism,” divorced from its particular connotations in this or that modern political context, refers broadly to a philosophy of individual rights, liberties, and responsibilities, coupled with respect for institutions and rule of law over personalized power. As Cass Sunstein construes the term, liberalism encompasses a broad tent, from Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher to Martin Luther King and Franklin Roosevelt. But liberalism is being challenged both from the right and from the left, by those who think that individual liberties can go too far. We talk about the philosophical case for liberalism as well as the challenges to it in modern politics, as discussed in his new book On Liberalism.

“Liberalism,” divorced from its particular connotations in this or that modern political context, refers broadly to a philosophy of individual rights, liberties, and responsibilities, coupled with respect for institutions and rule of law over personalized power. As Cass Sunstein construes the term, liberalism encompasses a broad tent, from Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher to Martin Luther King and Franklin Roosevelt. But liberalism is being challenged both from the right and from the left, by those who think that individual liberties can go too far. We talk about the philosophical case for liberalism as well as the challenges to it in modern politics, as discussed in his new book On Liberalism.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A 101 on how to benefit from Dr. GPT

Stephen McBride at the Rational Optimist Society:

“Should we bring him to the hospital?”

You never want to hear that from your wife at 5am.

Our 7-month-old son had woken up with angry red blotches all over his body. Measles?

Instead of going to the ER, I remembered my friend Tyler Cowen’s sage advice: You should ask AI more questions.

I snapped two photos of the rash and asked ChatGPT to evaluate.

In less than five seconds, ChatGPT said it was likely a common viral infection, nothing more serious. It also gave me specific warning signs that would warrant a trip to the ER.

The anxiety vanished, and we went back to sleep.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

David Deutsch: AGI, the origins of quantum computing, and the future of humanity

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Responsibility of Intellectuals in the Age of Fascism and Genocide

Robin D. G. Kelley in the Boston Review:

Fourteen years ago, Noam Chomsky published “The Responsibility of Intellectuals, Redux” in these pages. He used the occasion of the tenth anniversary of 9/11 to revisit his classic 1967 essay on the subject, although the immediate occasion for the piece was the assassination of Osama bin Laden by U.S. Navy Seals. As the Obama administration (and much of America) celebrated, Chomsky exposed the operation as a violation of U.S. and international law. The singular goal was to kill bin Laden, not capture him and bring him to trial. There was no pretense of habeas corpus since his body was summarily dumped into the sea.

Fourteen years ago, Noam Chomsky published “The Responsibility of Intellectuals, Redux” in these pages. He used the occasion of the tenth anniversary of 9/11 to revisit his classic 1967 essay on the subject, although the immediate occasion for the piece was the assassination of Osama bin Laden by U.S. Navy Seals. As the Obama administration (and much of America) celebrated, Chomsky exposed the operation as a violation of U.S. and international law. The singular goal was to kill bin Laden, not capture him and bring him to trial. There was no pretense of habeas corpus since his body was summarily dumped into the sea.

Chomsky thus reiterates his original contention that it is the “responsibility of intellectuals” to tell the truth about war—in this instance, the war on terror and the crimes of U.S. imperialism in the Middle East, Latin America, Asia, and Africa. Referring to decades of debate on the phrase, he notes, “The phrase is ambiguous: does it refer to intellectuals’ moral responsibility as decent human beings in a position to use their privilege and status to advance the causes of freedom, justice, mercy, peace, and other such sentimental concerns? Or does it refer to the role they are expected to play, serving, not derogating, leadership and established institutions?” His answer was clear: intellectuals must be guided by conscience and refuse to be beholden to state interests, either out of political loyalty or ideological commitment or both.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wenesday Poem

At Sea

talking with Perschke on the fantail. I ask him

“What time do you go on lookout?”

—”When the sun sets. But I can’t tell tonight, it’s

… cloudy.”

—”In Japan in the Buddhist temples they ring the evening

… bell when it gets so dark you can’t see the lines in

… your hand while sitting in your room.”

—”Full length or up close?”

—”Full length I guess.”

—”Suppose you got a long arm. Maybe you’re late. Are the

… windows open?”

—”Don’t have any windows. The walls are open.”

—”Always?”

—”Sometimes they’re closed.”

—”Can’t always ring it at the right time, huh. What do

… they ring it for anyway?”

—”Wake people up.”

—”But that’s in the evening.”

—”They ring it in the morning too.”

by Gary Snyder

from Earth House Hold

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Scientists Just Made ‘Biological Qubits’ That Act as Quantum Sensors Inside Cells

Edd Gent in Singularity Hub:

Fragile quantum states might seem incompatible with the messy world of biology. But researchers have now coaxed cells to produce quantum sensors made of proteins. Quantum states are incredibly sensitive to changes in the environment. This is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they can sense physical properties with unprecedented precision. At the same time, they’re extremely delicate and hard to work with. This sensitivity makes it challenging to create quantum sensors that work in living systems, which are warm, biochemically active, and in constant motion. Scientists have tried to integrate various kinds of synthetic quantum sensors into biology, but they’ve been bedeviled by problems related to targeting, efficiency, and durability.

Fragile quantum states might seem incompatible with the messy world of biology. But researchers have now coaxed cells to produce quantum sensors made of proteins. Quantum states are incredibly sensitive to changes in the environment. This is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they can sense physical properties with unprecedented precision. At the same time, they’re extremely delicate and hard to work with. This sensitivity makes it challenging to create quantum sensors that work in living systems, which are warm, biochemically active, and in constant motion. Scientists have tried to integrate various kinds of synthetic quantum sensors into biology, but they’ve been bedeviled by problems related to targeting, efficiency, and durability.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Stressors affect systemic inflammation, tumor aggressiveness in breast cancer

Elana Gotkine in Medical X Press:

For women with breast cancer, stressors are associated with deleterious alterations to the systemic and tumor immune environment, according to a study published online Feb. 14 in JAMA Network Open.

For women with breast cancer, stressors are associated with deleterious alterations to the systemic and tumor immune environment, according to a study published online Feb. 14 in JAMA Network Open.

…More favorable immune-stimulatory changes were seen in association with greater perceived social support (e.g., increased serum interleukin-5 and activated natural killer cells in noncancerous breast tissue of Black women). Associations were seen for higher levels of perceived stress, exposure to discrimination, and neighborhood deprivation with systemic inflammation, deleterious immune cell profiles, and aggressive tumor biologic characteristics. Distinct immunologic features associated with stressors were identified in Black women, including chemotaxis with stress and immune suppression with stress at the systemic level and increased tumor-associated myeloid cells at the tissue level. An association was seen for perceived stress with elevated tumor mutational burden.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, September 2, 2025

Dante’s success was far from guaranteed

Richard Hughes Gibson in The Hedgehog Review:

“Now he is scattered among a hundred cities,” W.H. Auden wrote in 1939, “And wholly given over to unfamiliar affections.” Auden was ruminating on the recent death of the Irish poet W.B. Yeats, but the words could serve as an epitaph for any great author. Poets like to imagine that their creations confer afterlives—for themselves and their subjects—impervious to the assaults of “wasteful war” and “sluttish time” so ruinous to monuments of marble or metal (see Horace’s Ode 3.30 and Shakespeare’s Sonnet 55). But as Auden recognized, the moment an author dies, his or her legacy is on the loose. Any chance those poems have of a future depends on what readers make of them: “The words of a dead man,” Auden continues, “Are modified in the guts of the living.”

“Now he is scattered among a hundred cities,” W.H. Auden wrote in 1939, “And wholly given over to unfamiliar affections.” Auden was ruminating on the recent death of the Irish poet W.B. Yeats, but the words could serve as an epitaph for any great author. Poets like to imagine that their creations confer afterlives—for themselves and their subjects—impervious to the assaults of “wasteful war” and “sluttish time” so ruinous to monuments of marble or metal (see Horace’s Ode 3.30 and Shakespeare’s Sonnet 55). But as Auden recognized, the moment an author dies, his or her legacy is on the loose. Any chance those poems have of a future depends on what readers make of them: “The words of a dead man,” Auden continues, “Are modified in the guts of the living.”

In Dante’s Divine Comedy: A Biography, Joseph Luzzi, literature professor at Bard College, offers a vivid account of this process of cultural digestion, and, at times, indigestion, from the Middle Ages to the present day. At first glance, such a slim book—little more than two hundred pages, including notes—would hardly seem adequate to the task, given the number, ardor, and productivity of Dante’s devotees over the centuries. Yet, as Luzzi argues in the introduction, those are exactly the reasons against attempting a truly comprehensive reception history of the Comedy (as Dante called it—Divine was added later by a Venetian printer). Such a study’s girth would be measured in hundreds of thousands of pages. No one would read it.

Instead, across ten chapters, Luzzi mixes passage analysis and brief case studies to illustrate the major trends in the Comedy’s reception.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Incalculable Costs of Corrupt Statistics

Diane Coyle at Project Syndicate:

The modern concept of GDP was developed in the 1930s and became firmly established during World War II, as it served a national purpose. While Germany was working on its own methods for gauging economic capacity, the United States and the United Kingdom gained a decisive strategic edge by being the first to define total output and compile reliable statistics. This enabled the Allies to maximize production and manage the sacrifices required of their citizens more effectively.

The modern concept of GDP was developed in the 1930s and became firmly established during World War II, as it served a national purpose. While Germany was working on its own methods for gauging economic capacity, the United States and the United Kingdom gained a decisive strategic edge by being the first to define total output and compile reliable statistics. This enabled the Allies to maximize production and manage the sacrifices required of their citizens more effectively.

Greece’s 2012 debt crisis underscores the dangers of unreliable economic data. For years, the country relied on inflated GDP figures and understated debt levels to borrow cheaply on international markets. Eurostat, the European Union’s statistical arm, and others cautioned that Greece’s statistics were misleading, but their warnings were largely unheeded – not least because banks were eager to profit from loan commissions.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How one unexpected element turned the rubber industry around

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The US really is unlike other rich countries when it comes to job insecurity – and AI could make it even more ‘exceptional’

Jeffrey C. Dixon in The Conversation:

How will AI affect American workers? There are two major narratives floating around. The “techno-optimist” view is that AI will free humans from boring tasks and create new jobs, while the “techno-pessimist” view is that AI will lead to widespread unemployment.

How will AI affect American workers? There are two major narratives floating around. The “techno-optimist” view is that AI will free humans from boring tasks and create new jobs, while the “techno-pessimist” view is that AI will lead to widespread unemployment.

As a sociologist who studies job insecurity, I’m among the pessimists. And that’s not just because of AI itself. It’s about something deeper – what scholars call “American exceptionalism.” While people commonly use this phrase to refer to anything that makes the U.S. unique, I use it narrowly to refer to the country’s approach to work and social welfare, which is quite different from the systems in other rich countries.

I suspect AI will “turbocharge” American exceptionalism in ways that make workers more afraid of losing their jobs. When fused with organizations’ adoption of new types of AI, workers’ fears may soon become reality, if they haven’t already.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Two Years of Doxxing at Harvard

Max Krupnick in Harvard Magazine:

On Wednesday, October 11, 2023, an unusual truck circled the streets surrounding Harvard Yard, pausing outside the bakery across from Widener Library. Three video screens on its sides showed the faces and names of Harvard students. Accompanying text, in newspaper typeface, labeled them “Harvard’s Leading Antisemites.”

On Wednesday, October 11, 2023, an unusual truck circled the streets surrounding Harvard Yard, pausing outside the bakery across from Widener Library. Three video screens on its sides showed the faces and names of Harvard students. Accompanying text, in newspaper typeface, labeled them “Harvard’s Leading Antisemites.”

By now, nearly everyone is familiar with how it happened. The day after the October 7, 2023, Hamas terrorist attacks on Israel, Harvard’s Palestine Solidarity Committee circulated a letter holding “the Israeli regime entirely responsible for all unfolding violence.” Representatives of 33 student organizations, from overtly political groups to a South Asian dance troupe, cosigned it. And amid the angry backlash, some prominent voices called out for a particular form of retribution. Investor Bill Ackman ’88, M.B.A. ’92, posted on X that Harvard should release the names of students who belonged to the signing groups “to insure [sic] none of us inadvertently hire any of their members.” If students support the letter, he continued, their views should be “publicly known.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How ageing changes our genes

Chris Simms in Nature:

The visible effects of ageing on our body are in part linked to invisible changes in gene activity. The epigenetic process of DNA methylation — the addition or removal of tags called methyl groups — becomes less precise as we age. The result is changes to gene expression that are linked to reduced organ function and increased susceptibility to disease as people age. Now, a meta-analysis of epigenetic changes in 17 types of human tissue throughout the entire adult lifespan provides the most comprehensive picture to date of how ageing modifies our genes.

The visible effects of ageing on our body are in part linked to invisible changes in gene activity. The epigenetic process of DNA methylation — the addition or removal of tags called methyl groups — becomes less precise as we age. The result is changes to gene expression that are linked to reduced organ function and increased susceptibility to disease as people age. Now, a meta-analysis of epigenetic changes in 17 types of human tissue throughout the entire adult lifespan provides the most comprehensive picture to date of how ageing modifies our genes.

The study assessed DNA methylation patterns in human tissue samples and revealed that some tissues seem to age faster than others. The retina and stomach, for example, accumulate more ageing-related DNA methylation changes than do the cervix or skin. The analysis also found universal epigenetic markers of ageing across different organs. This ‘epigenetic atlas’ might help researchers to study the link between DNA methylation and ageing and could aid the identification of molecular targets for anti-ageing treatments.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Dua Lipa in Conversation With Percival Everett

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Salt Statues: Carhué Cemetery, Buenos Aires

Mariana Enríquez at the Paris Review:

The concrete Christ designed by Francisco Salamone, severe like all his works are, emerged some time ago from the ultrasalty waters of the flooded Epecuén Lagoon. Now people leave offerings to it, partly in thanksgiving that the flood didn’t reach the town of Carhué, partly to pray that the town of Villa Epecuén will once again become the successful tourist resort that it was for decades, before it turned into the ruin it is today, a town haunted by trees so dry and salt-coated they look like they’re made of ash. White trees, ghost trees, triffid trees with their roots exposed, trees that look like spiders on an endless march.

I remember photographs of that Christ on the cross. The water had risen to cover his feet, and all around him were dead, half-submerged trees. The trees are still there, but the crucifix was moved a few meters closer to the city; it’s now on a wooden platform that you access by a ladder from the beach in front of the lake.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

September

September

and autumn creeps

into summer’s room

so many dresses

shade upon shade of green

too many

the young girl

wants something richer

to bring out

the cream of her skin

the sweep

of her dark hair

she fingers an oak leaf

imagining herself dancing

in that shape, but fiery, across the hills

smiles

yes

that will do

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

On Felix Shumba

Marissa Moorman at the LRB:

The female cabbage tree emperor moth (Bunaea alcinoe) is the size of a human hand. I saw one in 1992 in Zimbabwe’s Eastern Highlands, where the Vumba mountain range runs along the border with Mozambique; in the 1970s, ZANU guerrillas fighting for independence from white Rhodesia had hidden in the area. I snapped a shaky photo of the giant moth, beneath a dull outdoor light, with a pocket camera. I don’t know whether I still have the print, but it doesn’t matter. The image stayed with me. The moth was alone. Still. Unbothered. She seemed to own the night.

I remembered the moth when I visited the artist Felix Shumba at the International Studio and Curatorial Programme in Williamsburg, Brooklyn in March this year. Shumba, an artist from Zimbabwe, spent three months in the converted industrial space of the ISCP. Charcoal drawings hung on the walls. File folders were arranged on the floor in neat rows. Shumba had drawn oversized bugs on them in charcoal, including a moth. He makes the charcoal himself. It is light in the hand but his images are full of gravity. The human and animal figures sometimes seem to lift from the paper, as if they could step into the room.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.