Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Hermann Nitsch

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Yanis Varoufakis: Will Trump’s Working-Class Base Turn on Him?

Yanis Varoufakis at Project Syndicate:

Following the 2008 financial collapse, US capitalism changed forever. While the banks were bailed out, more and more workers with secure, high-quality employment found themselves among the “untouchables” scrounging for a living in short-term, low-paid, dead-end jobs. Whereas Reagan and the Bushes won elections because secure proletarians voted for them and untouchables were too disheartened to vote at all, Trump won by rallying the untouchables, who now included a growing number of hitherto secure proletarians.

Following the 2008 financial collapse, US capitalism changed forever. While the banks were bailed out, more and more workers with secure, high-quality employment found themselves among the “untouchables” scrounging for a living in short-term, low-paid, dead-end jobs. Whereas Reagan and the Bushes won elections because secure proletarians voted for them and untouchables were too disheartened to vote at all, Trump won by rallying the untouchables, who now included a growing number of hitherto secure proletarians.

Against the backdrop of Bill (and Hillary) Clinton’s open romancing of Wall Street, Barack Obama’s banker bailouts, and Joe Biden’s suicidal strategy of telling struggling people that the Democrats had delivered an “excellent” economy, Trump tapped into working-class rage. All it took to attract voters the Democrats had long since abandoned were some incoherent musings about a “broken” country and the “carnage” that feckless, self-interested elites had inflicted on people like them.

Democrats hope and pray that when the pain from Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill begins to bite, workers will desert him.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

On Hermann Nitsch’s Orgies Mysteries Theater

Göksu Kunak at Artforum:

What transpired next was a kind of Dionysian rural festival where performers hung carcasses and living bodies, animal and human, losing themselves in pouring, smearing, splashing—actions Nitsch had developed for years. Mythical figures became crucial scaffolds alongside Christian elements like garments, foot-washing, a grail, and the cross. Odysseus and Parsifal recurred as structural motifs that framed the choreography, scent, sound, and sacrificial acts: Odysseus as an emblem of the wandering heroic subject who must cross the threshold into chaos, the way the performers descend into a forest of flesh. Performers took their time carrying wooden structures for which human and animal bodies were used as embellishment. Huge white cloths were stretched, spattered with bright-red animal blood next to lilies, slaughtered flesh, and the symbolically crucified, tied-up human body.

What transpired next was a kind of Dionysian rural festival where performers hung carcasses and living bodies, animal and human, losing themselves in pouring, smearing, splashing—actions Nitsch had developed for years. Mythical figures became crucial scaffolds alongside Christian elements like garments, foot-washing, a grail, and the cross. Odysseus and Parsifal recurred as structural motifs that framed the choreography, scent, sound, and sacrificial acts: Odysseus as an emblem of the wandering heroic subject who must cross the threshold into chaos, the way the performers descend into a forest of flesh. Performers took their time carrying wooden structures for which human and animal bodies were used as embellishment. Huge white cloths were stretched, spattered with bright-red animal blood next to lilies, slaughtered flesh, and the symbolically crucified, tied-up human body.

In Nitsch’s work, disembodiment becomes a way to get back into the body. But there’s also something digital in his immersive choreography whereby everything, even nature, seems programmed. The sun set. Flowers smelled. Birds chirped. There was an ongoing pitch, a sound that lingered in the space, even when the actions stopped. It felt very weird to drink the Nitsch-branded Wine and talk.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Using Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy To Help the Body Heal

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A Prominent Buddhist Scholar’s Quest To Unify East And West

Costică Brădăţan at The American Scholar:

“Raised in Britain as a post-Christian secular humanist and trained in Asia as a Tibetan and Zen Buddhist monk,” Stephen Batchelor writes at the end of his book, Buddha, Socrates, and Us, “I find that I can no longer identify exclusively with either a Western or an Eastern tradition.” Decades of dwelling in these traditions—each with its own intellectual, spiritual, and philosophical riches—have left him strangely homeless. Far from making him unhappy, though, this state of existential homelessness has given Batchelor access to what he sees as a higher life. For, while “unsettling and disorienting” at times, such “spaces of uncertainty seem far richer in creative possibilities, more open to leading a life of wonder, imagination, and action.”

“Raised in Britain as a post-Christian secular humanist and trained in Asia as a Tibetan and Zen Buddhist monk,” Stephen Batchelor writes at the end of his book, Buddha, Socrates, and Us, “I find that I can no longer identify exclusively with either a Western or an Eastern tradition.” Decades of dwelling in these traditions—each with its own intellectual, spiritual, and philosophical riches—have left him strangely homeless. Far from making him unhappy, though, this state of existential homelessness has given Batchelor access to what he sees as a higher life. For, while “unsettling and disorienting” at times, such “spaces of uncertainty seem far richer in creative possibilities, more open to leading a life of wonder, imagination, and action.”

At its core, Batchelor’s Buddha, Socrates, and Us may be read as a response to a simple, yet important observation: everything in life tends to fall into patterns, to settle into habits and routines. Not even matters of the spirit—religion and philosophy, beliefs and ideas, thinking and writing—seem to escape this fate. Such mindless repetition makes our lives easier and more comfortable, at least on the outside, but to do things mechanically and unthinkingly is to invite emptiness and meaninglessness into our existence.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Why a Kiwi May Be the Perfect Snack

Caroline Legaspi in The New York Times:

Apples and bananas may be some of America’s favorite fruits. But nutrition experts say that kiwis deserve a spot in your shopping cart. These brown, fuzzy fruits with green, yellow or even red flesh are packed with beneficial nutrients like fiber and vitamin C. And on TikTok, wellness influencers rave about their digestive and sleep-inducing benefits. “Kiwis are having a moment right now, and for good reason,” said Judy Simon, a clinical dietitian at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle.

Apples and bananas may be some of America’s favorite fruits. But nutrition experts say that kiwis deserve a spot in your shopping cart. These brown, fuzzy fruits with green, yellow or even red flesh are packed with beneficial nutrients like fiber and vitamin C. And on TikTok, wellness influencers rave about their digestive and sleep-inducing benefits. “Kiwis are having a moment right now, and for good reason,” said Judy Simon, a clinical dietitian at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle.

Here’s why their spotlight is so well-deserved, and how incorporating kiwis into your diet may influence your health. Kiwis contain an impressive array of nutrients. A medium-sized fruit offers a little over two grams of fiber at just 48 calories. The skin is especially fiber-rich.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Monday, August 25, 2025

Trump’s Global War on Decarbonization

Mark Blyth and Daniel Driscoll at Project Syndicate:

The US sits atop vast reserves of fossil fuels, which have underpinned its national prosperity for decades. They have lit cities, powered factories, stimulated postwar job growth, and forged broad regional political coalitions among labor, agriculture, and corporations. They are also highly profitable commodities, with exports creating global dependence on US supplies (which is especially true for liquefied natural gas following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine). Fossil fuels are a core component of the country’s political economy – and a key factor in US domestic and foreign policymaking.

The US sits atop vast reserves of fossil fuels, which have underpinned its national prosperity for decades. They have lit cities, powered factories, stimulated postwar job growth, and forged broad regional political coalitions among labor, agriculture, and corporations. They are also highly profitable commodities, with exports creating global dependence on US supplies (which is especially true for liquefied natural gas following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine). Fossil fuels are a core component of the country’s political economy – and a key factor in US domestic and foreign policymaking.

The Trump administration recognizes this. It includes ideological realists who understand that energy transitions make hegemons – that energy is power. Just as coal drove the industrial revolution in England, oil and gas fueled America’s postwar dominance. Whoever controls energy controls the future.

Unfortunately for the US, if the next energy transition is a green one, the future surely belongs to China, whose green-tech dominance is so firmly established that it does not really matter which metric you look at.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Sarin shortcut: How AI lowers the bar for chemical weapons

Ashutosh Jogalekar at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists:

For those contemplating mass casualties, biotoxins like ricin are easy to produce. But delivering them effectively is difficult, requiring specialized techniques like aerosolization. Conversely for chemical warfare agents like sarin, synthesis (because of restricted precursors) has traditionally been the hard part, even if delivering them does not require specialized methods.

For those contemplating mass casualties, biotoxins like ricin are easy to produce. But delivering them effectively is difficult, requiring specialized techniques like aerosolization. Conversely for chemical warfare agents like sarin, synthesis (because of restricted precursors) has traditionally been the hard part, even if delivering them does not require specialized methods.

However, that balance is tipping because of advances in artificial intelligence. Generative AI and off-the-shelf computational tools are collapsing the precursor barrier, making DIY sarin analogs (compounds that resemble the molecular structure of sarin) as attractive as castor-bean mash for rogue individuals. These applications can make the synthesis and use of nerve agents for nefarious purposes marginally but consequentially more probable.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

David Brooks talks to Tyler Cowen about Audacity, AI, and the American Psyche

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Fiction and the Fantastic: Stories by Jorge Luis Borges

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How To Fix DEI

Rachel Kleinfeld at Persuasion:

Recent assaults on DEI from the right have caused people who care about a diverse, inclusive America to circle the wagons against attacks from people who, at best, want to pretend the country is already colorblind, and at worst, want a return to an era when White, Christian men presided unquestioned at the top of the status hierarchy. But proponents of diversity do need to alter these programs—not to please those who want to go backward, but to help America become the inclusive nation it needs to be moving forward.

Recent assaults on DEI from the right have caused people who care about a diverse, inclusive America to circle the wagons against attacks from people who, at best, want to pretend the country is already colorblind, and at worst, want a return to an era when White, Christian men presided unquestioned at the top of the status hierarchy. But proponents of diversity do need to alter these programs—not to please those who want to go backward, but to help America become the inclusive nation it needs to be moving forward.

If America is to remain a democracy, demographic reality means that its politics and culture must become ever more inclusive. According to U.S. census data, in 1860 Whites comprised 86% of the population. A century later, the number had gone up slightly to 89%. And then it began to fall, fast. By 2023, only 62 percent of Americans identified as solely White.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Creature of the Late Afternoon

E. Tammy Kim at n+1:

There’s a movement, or voguish tendency, in South Korea called 4B, which emerged online as part of a #MeToo-style feminist resurgence in 2016. It pushed a four-pronged refusal of marriage, reproduction, dating, and sex. (The B is for 비 bhee, meaning un- or anti-.) When a right-wing prosecutor named Yoon Suk Yeol rallied men’s-rights voters to win the nation’s presidency in 2022, the feminist wave seemed decidedly over. But Trump’s reelection two years later provoked an American interest in 4B. According to some viral TikToks and newspaper articles, American women were disavowing heterosexual habits. The dust of 4B in Korea swirled temporarily back to life.

I was in Seoul with my parents when I noticed the Korean social media posts quoting US social media posts celebrating dated Korean social media posts. My editor asked me to write a short piece about 4B, which I started to outline at the dining table of our rental in the Itaewon neighborhood, near the decommissioned US military base.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Reality Is Evil

Drew M Dalton at Aeon Magazine:

Consider Friedrich Nietzsche, one of the first thinkers of the 19th century who saw the emerging thermodynamic revolution as a pathway to a new vision of the cosmos. What he saw was neither good nor evil, but simply a ‘monster of energy, without beginning, without end; a firm, iron magnitude of force that does not grow bigger or smaller, that does not expend itself but only transforms.’ However, Nietzsche seems to have overlooked the second and third laws of thermodynamics, which complicates (or nullifies) his optimism in the infinite creative potency of reality. The same could not be said for his contemporary Philipp Mainländer, who drew upon all three of the laws of thermodynamics to establish a metaphysical foundation for a new pessimistic philosophy. In the inevitable decay and destruction, Mainländer saw a new basis for the moral resignation and quietism dominating German intellectual circles at the time.

Consider Friedrich Nietzsche, one of the first thinkers of the 19th century who saw the emerging thermodynamic revolution as a pathway to a new vision of the cosmos. What he saw was neither good nor evil, but simply a ‘monster of energy, without beginning, without end; a firm, iron magnitude of force that does not grow bigger or smaller, that does not expend itself but only transforms.’ However, Nietzsche seems to have overlooked the second and third laws of thermodynamics, which complicates (or nullifies) his optimism in the infinite creative potency of reality. The same could not be said for his contemporary Philipp Mainländer, who drew upon all three of the laws of thermodynamics to establish a metaphysical foundation for a new pessimistic philosophy. In the inevitable decay and destruction, Mainländer saw a new basis for the moral resignation and quietism dominating German intellectual circles at the time.

In the 20th century, thinkers like Isabelle Stengers and Bernard Stiegler have drawn upon the insights of the thermodynamic revolution to argue for what the former sees as the fundamental indeterminacy of reality and what the latter argues is the driving force of social and political developments since the Industrial Revolution.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

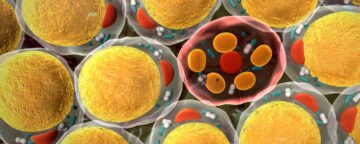

Aggressive Breast Cancers Steal Energy from Nearby Fat Cells

Shelby Bradford in TheScientist:

Patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) have more aggressive, invasive tumors and fewer treatment options than other kinds of breast cancers. TNBC tumors use fatty acid oxidation as a key part of their metabolism.1 Coupled with studies that showed people with higher body mass indexes are more likely to develop TNBC, researchers suspected that adipose tissue influenced tumor growth.2 However, the mechanism underlying this relationship was unclear.

Patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) have more aggressive, invasive tumors and fewer treatment options than other kinds of breast cancers. TNBC tumors use fatty acid oxidation as a key part of their metabolism.1 Coupled with studies that showed people with higher body mass indexes are more likely to develop TNBC, researchers suspected that adipose tissue influenced tumor growth.2 However, the mechanism underlying this relationship was unclear.

In a study published in Nature Communications, Andrei Goga, a cancer biologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and his team showed that TNBC cells form bridges to nearby fat cells and activate lipolysis in adipocytes to release fatty acids.3 The researchers showed that blocking this process halted tumor growth in mice. “This is a golden opportunity for us to develop effective strategies to treat the most aggressive forms of breast cancer,” Goga said in a press release.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How a self-taught biologist transformed nature writing — and inspired Darwin

Sunday, August 24, 2025

Creatures Apart

Vivian Gornick on Shulamith Firestone’s portraits of madness, in Boston Review:

When I was a girl in the 1950s women, for the most part, got married, gave birth, and stayed home; if necessary, they went to work as schoolteachers or secretaries or salesgirls. They did not enter the professions, start a business, serve in government, or become university professors; nor did they climb a telephone pole, go down in the mines, or compete in a marathon. Today a girl is born with the knowledge that not only can she do any or all of the above, it is even assumed that she will pursue a working life as well as a domestic one. The change in social expectations for women, nothing short of monumental, is due to the Second Wave of American feminism (otherwise known as the Women’s Liberation Movement), a political and social development characterized by the twin efforts of liberals who worked throughout the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s to achieve equality for women under the law and radicals who worked to eradicate deep-dyed, historic sexism through a change in cultural consciousness. Among the leading figures in this second group was Shulamith Firestone, of whom it was said, “I think of her as a shooting star. She flashed brightly across the midnight sky, and then she disappeared.” That’s exactly how I remember her.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

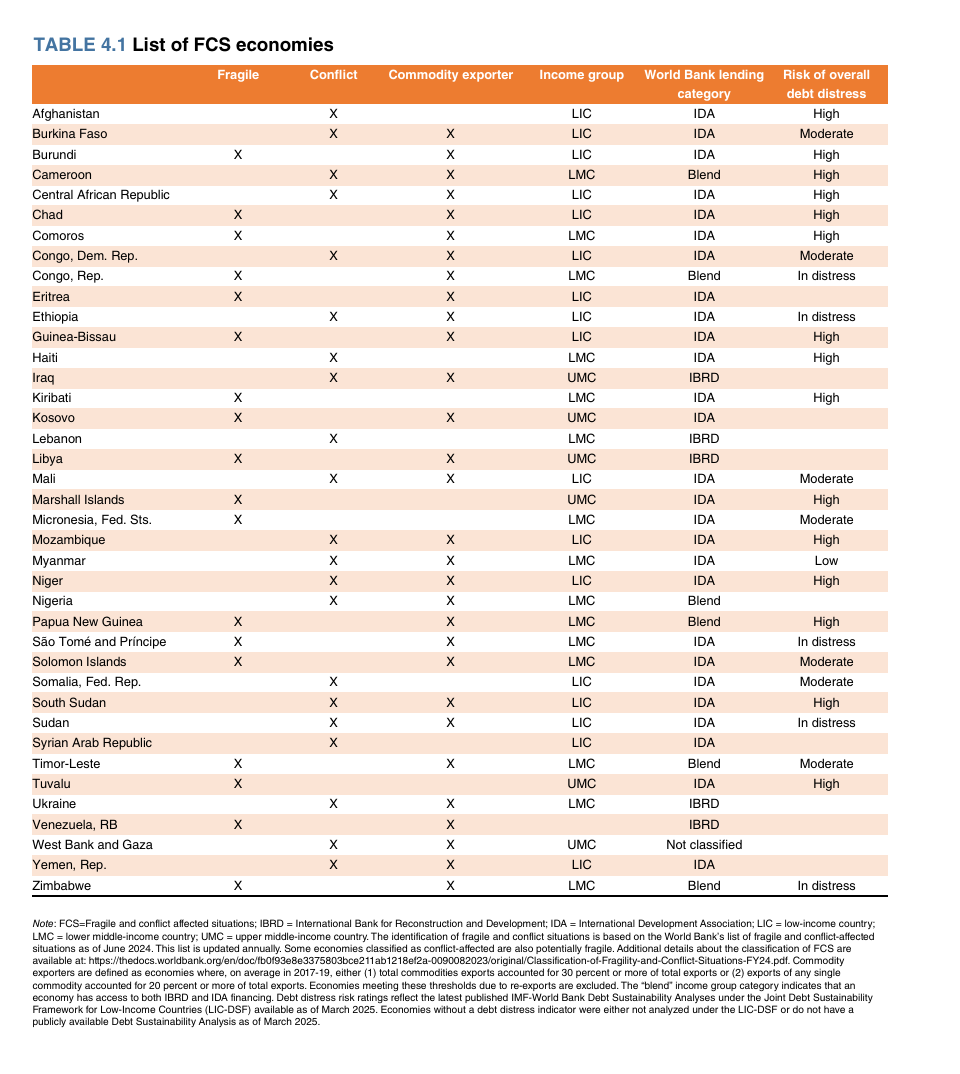

Violence and (de)development: From Gaza to “fragile and conflict-affected situations”

Adam Tooze in Chartbook:

Starting with Gaza and asking where else people starve and fight for their lives is an urgent and productive task. I wrote about the question a few weeks ago. I am prompted to return to it by a new publication by a team at the World Bank.

As I argued in the previous post: Gaza is an extreme case because it involves a rich and powerful state victimizing a tightly controlled and largely defenseless population under a state of siege with the explicit intent of ethnic cleansing in conjunction with an ongoing settler-colonial project. Writing in the 1940s Raphael Lemkin struggled to find categories to describe just such a case in Nazi occupied Poland. The neologism he coined was genocide.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sari Nusseibeh on Philosophy and Conflict

In Philosophy Bites, David Edmonds and Nigel Warburton interview Sari Nusseibeh:

Host 1: We’re talking today about philosophy and conflict. But before we get into that, perhaps you can tell us a bit about your early years because you’re born into a a very famous and distinguished Palestinian family.

Guest: Yes. I was born into a family that considers itself to be distinguished. Our family name, Nasebeh, comes from the very, very distant past. It’s the name of a woman who supposedly fought alongside the prophet Muhammad. And in theory, we actually came to Jerusalem right from that time.

Guest: I was born personally in Damascus. That was during the early wars that created Israel and created, on the other hand, the Palestinian refugee problem. My parents’ mother was in Damascus. I was born there. But a year or two later after my birth, I came to Jerusalem and grew up in Jerusalem.

Host 1: And then you went to Oxford as an undergraduate at a time when Wittgenstein and linguistic philosophy more generally was dominant. Ordinary language in particular, the idea that philosophical problems as it were dissolve in the analysis of language, that’s very much gone out of fashion. But I wonder whether its influence has stayed with you, what the importance of your Oxford philosophy was.

Guest: Well, I think the primary importance has to do not with the theory of linguistics or the theory of philosophy of language as such, but with the way philosophy tutors are conducted. And in my case, I was very lucky to have as a tutor Oscar Wood. Although he did not necessarily like me, I was quite fond of him, and he has remained with me ever since. He was the kind of person who made you always search for good reasons for holding the view that you hold or the opinion that you hold. And this has stayed with me.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Shulamith Firestone’s portraits of madness reveal a condition afflicting us all

Vivian Gornick in Boston Reviews:

When I was a girl in the 1950s women, for the most part, got married, gave birth, and stayed home; if necessary, they went to work as schoolteachers or secretaries or salesgirls. They did not enter the professions, start a business, serve in government, or become university professors; nor did they climb a telephone pole, go down in the mines, or compete in a marathon. Today a girl is born with the knowledge that not only can she do any or all of the above, it is even assumed that she will pursue a working life as well as a domestic one. The change in social expectations for women, nothing short of monumental, is due to the Second Wave of American feminism (otherwise known as the Women’s Liberation Movement), a political and social development characterized by the twin efforts of liberals who worked throughout the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s to achieve equality for women under the law and radicals who worked to eradicate deep-dyed, historic sexism through a change in cultural consciousness. Among the leading figures in this second group was Shulamith Firestone, of whom it was said, “I think of her as a shooting star. She flashed brightly across the midnight sky, and then she disappeared.” That’s exactly how I remember her.

When I was a girl in the 1950s women, for the most part, got married, gave birth, and stayed home; if necessary, they went to work as schoolteachers or secretaries or salesgirls. They did not enter the professions, start a business, serve in government, or become university professors; nor did they climb a telephone pole, go down in the mines, or compete in a marathon. Today a girl is born with the knowledge that not only can she do any or all of the above, it is even assumed that she will pursue a working life as well as a domestic one. The change in social expectations for women, nothing short of monumental, is due to the Second Wave of American feminism (otherwise known as the Women’s Liberation Movement), a political and social development characterized by the twin efforts of liberals who worked throughout the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s to achieve equality for women under the law and radicals who worked to eradicate deep-dyed, historic sexism through a change in cultural consciousness. Among the leading figures in this second group was Shulamith Firestone, of whom it was said, “I think of her as a shooting star. She flashed brightly across the midnight sky, and then she disappeared.” That’s exactly how I remember her.

Although I, too, was a Second Wave feminist, I functioned in the Movement more as a writer than a group-oriented activist. In fact, I first met Shulamith when I interviewed her for my first feminist piece for the Village Voice. I can still see her that day in 1969, sitting in the kitchen of her fourth-floor Lower East Side walk-up—small, fierce, large dark eyes peering out at me from the middle of that extraordinary mane of waist-length black hair—answering my every question with the rapid-fire rhetorical skill that marked her every utterance. It was no surprise to me when, the following year, her first book, The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution was published and I, along with the rest of the world, felt the full force of her Talmudic brilliance.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Born in 1720, White was educated at the University of Oxford, UK, before settling at The Wakes — his family home in Selborne, UK — in around 1757. Then, from 1768, he worked for 25 years on his Naturalist’s Journal, a columnar diary in which each page covered a week of observations on fruit and vegetable experiments, local creatures and weather conditions. White’s daily entries in Selborne were often haiku-like in their simplicity. He described “vast rocklike, distant clouds” or simply stated “Bees swarm much. Sheep are shorn.”

Born in 1720, White was educated at the University of Oxford, UK, before settling at The Wakes — his family home in Selborne, UK — in around 1757. Then, from 1768, he worked for 25 years on his Naturalist’s Journal, a columnar diary in which each page covered a week of observations on fruit and vegetable experiments, local creatures and weather conditions. White’s daily entries in Selborne were often haiku-like in their simplicity. He described “vast rocklike, distant clouds” or simply stated “Bees swarm much. Sheep are shorn.”