Sam Leith in The Guardian:

In this clever book, Stuart Jeffries starts out at a double disadvantage, though. First: he has an excellently snappy title but it’s open to question whether stupidity can be said to have a history in any meaningful sense. The quality of stupidity is just, sort of, there; and there’s lots of it. Could you write a history of happiness, or bad luck, or knees? You’d be on firmer ground, as he recognises, historicising the concept of stupidity: a short history, in other words, of “stupidity” – how successive societies and thinkers have defined and responded to reason’s derr-brained secret sharer. As an intellectual historian who has written smart and chewy popular books about the Frankfurt School (Grand Hotel Abyss) and postmodernism (Everything, All the Time, Everywhere), he certainly has the chops for it.

In this clever book, Stuart Jeffries starts out at a double disadvantage, though. First: he has an excellently snappy title but it’s open to question whether stupidity can be said to have a history in any meaningful sense. The quality of stupidity is just, sort of, there; and there’s lots of it. Could you write a history of happiness, or bad luck, or knees? You’d be on firmer ground, as he recognises, historicising the concept of stupidity: a short history, in other words, of “stupidity” – how successive societies and thinkers have defined and responded to reason’s derr-brained secret sharer. As an intellectual historian who has written smart and chewy popular books about the Frankfurt School (Grand Hotel Abyss) and postmodernism (Everything, All the Time, Everywhere), he certainly has the chops for it.

But then there’s the second problem: definitions. Is stupidity the same thing as ignorance? As foolishness? As the unwillingness to learn (AKA obtuseness, or what the Greeks called amathia)? As the inability to draw the right conclusions from what you have learned? Is it a quality of person or a quality of action? On and off, in ordinary usage, it’s all of these. It’s a know-it-when-you-see-it (except in yourself) thing.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

In 2025,

In 2025,  Every generation thinks it’s witnessing humanity’s moral collapse. New York Times columnist

Every generation thinks it’s witnessing humanity’s moral collapse. New York Times columnist  “The personal is the political” was a reality for me long before it became the mantra of Second Wave feminism in the United States. In 1951, when I was ten years old, my father, Samuel Wallach, a New York City high school teacher, was suspended from his job for refusing to cooperate with an investigation into communism in the public schools. He was fired for insubordination two years later—one of some 350 teachers who were fired or resigned in those years.

“The personal is the political” was a reality for me long before it became the mantra of Second Wave feminism in the United States. In 1951, when I was ten years old, my father, Samuel Wallach, a New York City high school teacher, was suspended from his job for refusing to cooperate with an investigation into communism in the public schools. He was fired for insubordination two years later—one of some 350 teachers who were fired or resigned in those years. During these first nine months

During these first nine months UFOs exist. On that we can all agree. The question is not whether they are but what they are.

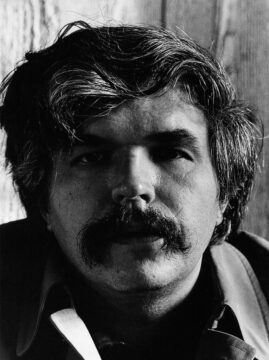

UFOs exist. On that we can all agree. The question is not whether they are but what they are. Brakhage virtually invented and singularly dominated the characteristic genre of American avant-garde cinema: the crisis film, that lyric articulation of the moods and observations of the filmmaker, following a rhythmical association of images without a predetermined scenario or enacted drama. Since the early ’60s he handpainted on film so elaborately that he brought that way of filmmaking, at least as old as Len Lye’s work in the mid-’30s, to new profundities. It became the predominant process of his filmmaking in the ’90s. Perhaps a quarter of his oeuvre was made without using a camera.

Brakhage virtually invented and singularly dominated the characteristic genre of American avant-garde cinema: the crisis film, that lyric articulation of the moods and observations of the filmmaker, following a rhythmical association of images without a predetermined scenario or enacted drama. Since the early ’60s he handpainted on film so elaborately that he brought that way of filmmaking, at least as old as Len Lye’s work in the mid-’30s, to new profundities. It became the predominant process of his filmmaking in the ’90s. Perhaps a quarter of his oeuvre was made without using a camera. I looked at my wife. Her eyes — soulful, brown, impossibly beautiful — met mine. I had looked into them thousands of times before, but in that moment, I wondered: Had I ever really seen them?

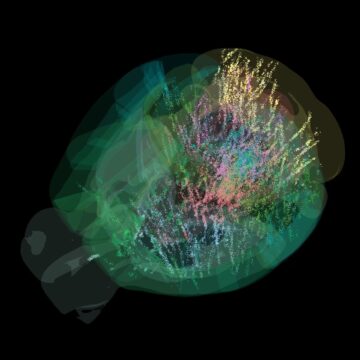

I looked at my wife. Her eyes — soulful, brown, impossibly beautiful — met mine. I had looked into them thousands of times before, but in that moment, I wondered: Had I ever really seen them? Neuroscientists from 22 labs joined forces in an unprecedented international partnership to produce a landmark achievement: a neural map that shows activity across the entire brain during decision-making.

Neuroscientists from 22 labs joined forces in an unprecedented international partnership to produce a landmark achievement: a neural map that shows activity across the entire brain during decision-making. Polycrisis is a descriptor that the establishment can agree on without challenging itself. It abstracts the causes of crises, making them appear as natural convergences rather than the systemic outcomes of extractive and exclusionary orders. And it makes the concept appear global when in fact the voices, experiences, and priorities it reflects are overwhelmingly Eurocentric.

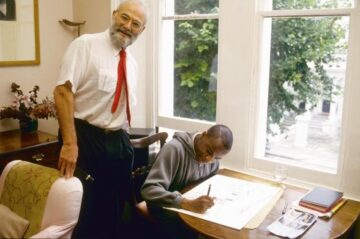

Polycrisis is a descriptor that the establishment can agree on without challenging itself. It abstracts the causes of crises, making them appear as natural convergences rather than the systemic outcomes of extractive and exclusionary orders. And it makes the concept appear global when in fact the voices, experiences, and priorities it reflects are overwhelmingly Eurocentric. To think today of the late Oliver Sacks, physician and author, is to bring to mind the extraordinary fellow human beings whose defects and gifts, depicted in Sacks’s books and essays, made the world a bit larger and much more interesting: the twin autistic boys who could instantly recall hundred-digit figures; the man who could not identify the person at whom he was staring in the mirror; the sailor for whom the distant past was detailed and vividly clear but for whom the immediate past had no existence; the woman without an awareness that she had been enclosed for sixty years in a body, her own; and, of course, the scores of victims of the 1920s encephalitis epidemic who had been treated with the new L-DOPA drug, and had recovered for a brief period the awareness of living. All these human exceptions peopled the world of medicine that Sacks created for his readers.

To think today of the late Oliver Sacks, physician and author, is to bring to mind the extraordinary fellow human beings whose defects and gifts, depicted in Sacks’s books and essays, made the world a bit larger and much more interesting: the twin autistic boys who could instantly recall hundred-digit figures; the man who could not identify the person at whom he was staring in the mirror; the sailor for whom the distant past was detailed and vividly clear but for whom the immediate past had no existence; the woman without an awareness that she had been enclosed for sixty years in a body, her own; and, of course, the scores of victims of the 1920s encephalitis epidemic who had been treated with the new L-DOPA drug, and had recovered for a brief period the awareness of living. All these human exceptions peopled the world of medicine that Sacks created for his readers. ADHD exists in this odd diagnostic liminal space where we know it’s a thing, but it’s hard to definitively pinpoint it in the physical structures of the brain. MRI studies have given us mixed signals over the years. Some say kids with smaller gray matter volumes in their brains are more likely to

ADHD exists in this odd diagnostic liminal space where we know it’s a thing, but it’s hard to definitively pinpoint it in the physical structures of the brain. MRI studies have given us mixed signals over the years. Some say kids with smaller gray matter volumes in their brains are more likely to  Artificial meat is under attack: US states like Montana, Mississippi and Alabama have banned it – taking the lead from

Artificial meat is under attack: US states like Montana, Mississippi and Alabama have banned it – taking the lead from  I just read the above-titled book by Jonathan Gottschall. It was really interesting–he convincingly argues that (a) stories are a central part of lives and always will be, and (b) stories are dangerous and we’re living in a world of dangerous stories. The book isn’t perfect–the author is a bit too credulous for my taste in citing dubious social-psychology studies–but no book is perfect, and I got a lot out of it, and now that I’ve read it, I feel pretty much in agreement with its arguments.

I just read the above-titled book by Jonathan Gottschall. It was really interesting–he convincingly argues that (a) stories are a central part of lives and always will be, and (b) stories are dangerous and we’re living in a world of dangerous stories. The book isn’t perfect–the author is a bit too credulous for my taste in citing dubious social-psychology studies–but no book is perfect, and I got a lot out of it, and now that I’ve read it, I feel pretty much in agreement with its arguments.