Matthew Yglesias at Slow Boring:

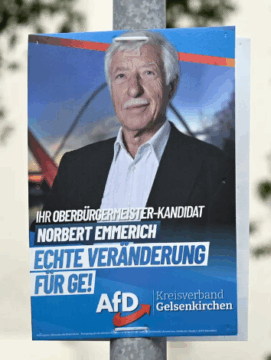

Almost all theories in elite discourse about why people vote for right-wing populism posit that deindustrialization or free trade or “neoliberalism” or some other thing that left-wing intellectuals think is bad induces support for political parties on the right.

Almost all theories in elite discourse about why people vote for right-wing populism posit that deindustrialization or free trade or “neoliberalism” or some other thing that left-wing intellectuals think is bad induces support for political parties on the right.

A simpler explanation is that a significant minority of the public in most Western countries agrees with right-wing cultural politics.

I tend to believe that the latter is true.

For example, many rank-and-file G.O.P. primary voters circa 2015 were a bit more moderate than Republican leaders on topics like Social Security and Medicare but more right-wing on immigration and crime. So when Trump offered that set of issue positions during the primaries, his platform resonated with a lot of voters.

This hypothesis tends to be under-explored in the scholarly literature, I think, because researchers are overwhelmingly left-wing themselves.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Carlisle illustrates the difference with a children’s fable told in Karen Blixen’s Out of Africa. In brief: a man stumbles around in the mud for a while in the middle of the night. He loses his way, changes direction and trips over a few things before going back to bed. Only when he wakes up and sees the scene by daylight does he realise that his footprints have traced out a perfect picture of a stork. The point is that, by living, we create a meaningful picture without knowing it – unless we attain some inkling of that wider view through art or mysticism.

Carlisle illustrates the difference with a children’s fable told in Karen Blixen’s Out of Africa. In brief: a man stumbles around in the mud for a while in the middle of the night. He loses his way, changes direction and trips over a few things before going back to bed. Only when he wakes up and sees the scene by daylight does he realise that his footprints have traced out a perfect picture of a stork. The point is that, by living, we create a meaningful picture without knowing it – unless we attain some inkling of that wider view through art or mysticism. Growing up, one of the first things I learned from the Bible was the commandment Thou shalt not kill. This makes sense considering that the religious community I belong to—the Bruderhof—is rooted in Anabaptism, a Christian tradition that, with occasional exceptions, has been pacifist since 1525. (The Anabaptist movement, which also includes the Amish, Mennonites and Hutterites, celebrates its quincentenary this year.) Over the sixteenth century, thousands of Anabaptists were executed as traitors to Christendom by Catholic and Protestant rulers. No doubt that’s why their signature virtue was Gelassenheit—“self-abandonment,” “submission,” “readiness to suffer.” It’s an ethic Nietzsche would have hated.

Growing up, one of the first things I learned from the Bible was the commandment Thou shalt not kill. This makes sense considering that the religious community I belong to—the Bruderhof—is rooted in Anabaptism, a Christian tradition that, with occasional exceptions, has been pacifist since 1525. (The Anabaptist movement, which also includes the Amish, Mennonites and Hutterites, celebrates its quincentenary this year.) Over the sixteenth century, thousands of Anabaptists were executed as traitors to Christendom by Catholic and Protestant rulers. No doubt that’s why their signature virtue was Gelassenheit—“self-abandonment,” “submission,” “readiness to suffer.” It’s an ethic Nietzsche would have hated. Cole Escola, the actor and playwright, stood before a mirror at a pastel-colored studio in Manhattan’s garment district, holding a spray of white satin flowers in one hand. “The calla lilies are in bloom again,” Escola said, quoting a

Cole Escola, the actor and playwright, stood before a mirror at a pastel-colored studio in Manhattan’s garment district, holding a spray of white satin flowers in one hand. “The calla lilies are in bloom again,” Escola said, quoting a  David Baltimore

David Baltimore O

O In the early 1800s, the French mathematician Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier discovered a way to take any function and decompose it into a set of fundamental waves, or frequencies. Add these constituent frequencies back together, and you’ll get your original function. The technique, today called the Fourier transform, allowed the mathematician — previously an ardent proponent of the French revolution — to spur a mathematical revolution as well.

In the early 1800s, the French mathematician Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier discovered a way to take any function and decompose it into a set of fundamental waves, or frequencies. Add these constituent frequencies back together, and you’ll get your original function. The technique, today called the Fourier transform, allowed the mathematician — previously an ardent proponent of the French revolution — to spur a mathematical revolution as well. EU leaders “jokingly call me the president of Europe,” Donald Trump

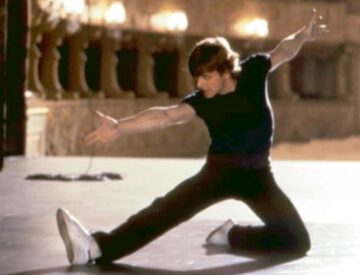

EU leaders “jokingly call me the president of Europe,” Donald Trump  From the moment Baryshnikov landed in New York he was hungry to learn new roles and to have works created for him. In quick succession, he performed Frederick Ashton’s La Fille mal gardée, Roland Petit’s Le Jeune Homme et la Mort, John Butler’s Medea, Antony Tudor’s Shadowplay, Michel Fokine’s Le Spectre de la Rose, Jerome Robbins’ Other Dances, Alvin Ailey’s Pas de Duke, a total of about two dozen new roles in two years according to the book Baryshnikov at Work. His most significant collaboration was with the modern-dance choreographer Twyla Tharp, who created Push Comes to Shove, a work in which he revealed a new, vaudevillian side, around Baryshnikov’s talents. This ballet provided the audience with the first inkling of Baryshnikov’s new “American” persona. In 1977 and early 1978, he also débuted in two essential male roles by Balanchine: Prodigal Son and Apollo. Neither début took place at New York City Ballet, nor did he learn the choreography or receive coaching from Balanchine.

From the moment Baryshnikov landed in New York he was hungry to learn new roles and to have works created for him. In quick succession, he performed Frederick Ashton’s La Fille mal gardée, Roland Petit’s Le Jeune Homme et la Mort, John Butler’s Medea, Antony Tudor’s Shadowplay, Michel Fokine’s Le Spectre de la Rose, Jerome Robbins’ Other Dances, Alvin Ailey’s Pas de Duke, a total of about two dozen new roles in two years according to the book Baryshnikov at Work. His most significant collaboration was with the modern-dance choreographer Twyla Tharp, who created Push Comes to Shove, a work in which he revealed a new, vaudevillian side, around Baryshnikov’s talents. This ballet provided the audience with the first inkling of Baryshnikov’s new “American” persona. In 1977 and early 1978, he also débuted in two essential male roles by Balanchine: Prodigal Son and Apollo. Neither début took place at New York City Ballet, nor did he learn the choreography or receive coaching from Balanchine. It was in the summer of 1835 that a report landed, with what was surely an ominous thud, on the desk of Carl Sigmund Franz Freiherr vom Stein zum Altenstein – the book is worth reading for the names alone – the Prussian minister of church affairs, based in Berlin, which was a very long way from Königsberg, capital of East Prussia. Königsberg’s renown derived chiefly from the presence at the city’s university, the Albertina, of the philosopher Immanuel Kant. After his death in 1804, however, the Albertina ‘lapsed into the status of a sleepy provincial college’. The diminution of the intellectual tone in the city may account for some of the religious excesses that Clark recounts.

It was in the summer of 1835 that a report landed, with what was surely an ominous thud, on the desk of Carl Sigmund Franz Freiherr vom Stein zum Altenstein – the book is worth reading for the names alone – the Prussian minister of church affairs, based in Berlin, which was a very long way from Königsberg, capital of East Prussia. Königsberg’s renown derived chiefly from the presence at the city’s university, the Albertina, of the philosopher Immanuel Kant. After his death in 1804, however, the Albertina ‘lapsed into the status of a sleepy provincial college’. The diminution of the intellectual tone in the city may account for some of the religious excesses that Clark recounts. An unusual experience

An unusual experience