Sophie McBain in The Guardian:

A maths lecturer, convinced his wife is cheating, will not check the CCTV footage that might confirm his fears but instead keeps a private tally of the number of pubic hairs she sheds in her underwear. One hair is “OK, acceptable”, more is evidence that she has been “having it off”, he says, unaware that he uses these delusions of her infidelity to protect himself from the dangers of intimacy. A high-flying Fulbright scholar becomes a sex worker to avenge the father she hates. An ex-nun discovers that her decades of religious seclusion were driven by an unconscious fear of pregnancy. A troubled young woman, seeking redress for her psychological losses, steals large sums of money that she will never spend.

A maths lecturer, convinced his wife is cheating, will not check the CCTV footage that might confirm his fears but instead keeps a private tally of the number of pubic hairs she sheds in her underwear. One hair is “OK, acceptable”, more is evidence that she has been “having it off”, he says, unaware that he uses these delusions of her infidelity to protect himself from the dangers of intimacy. A high-flying Fulbright scholar becomes a sex worker to avenge the father she hates. An ex-nun discovers that her decades of religious seclusion were driven by an unconscious fear of pregnancy. A troubled young woman, seeking redress for her psychological losses, steals large sums of money that she will never spend.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

T

T There is so much hype around AI, especially in the market. If you want to sell something to people today, you call it AI. Not every automatic machine is an AI. What makes AI AI is that it is able to learn and change by itself and come up with decisions and ideas that we don’t anticipate, can’t anticipate.

There is so much hype around AI, especially in the market. If you want to sell something to people today, you call it AI. Not every automatic machine is an AI. What makes AI AI is that it is able to learn and change by itself and come up with decisions and ideas that we don’t anticipate, can’t anticipate. AI psychosis (

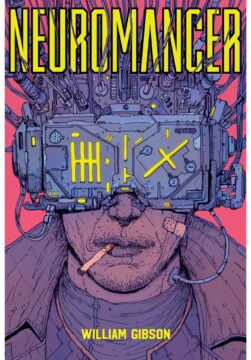

AI psychosis ( In fact, it is Gibson’s critique of what he calls the “

In fact, it is Gibson’s critique of what he calls the “ In the popular imagination, the history of sex is a straightforward one. For centuries, the people of the Christian West lived in a state of sexual repression, straitjacketed by an overwhelming fear of sin, combined with a complete lack of knowledge about their own bodies. Those who fell short of the high moral standards that church, state and society demanded of them faced ostracism and punishment. Then in the mid-20th century things changed forever when, in Philip Larkin’s oft-quoted words, ‘Sexual intercourse began in 1963 … between the end of the Chatterley ban and the Beatles’ first LP.’

In the popular imagination, the history of sex is a straightforward one. For centuries, the people of the Christian West lived in a state of sexual repression, straitjacketed by an overwhelming fear of sin, combined with a complete lack of knowledge about their own bodies. Those who fell short of the high moral standards that church, state and society demanded of them faced ostracism and punishment. Then in the mid-20th century things changed forever when, in Philip Larkin’s oft-quoted words, ‘Sexual intercourse began in 1963 … between the end of the Chatterley ban and the Beatles’ first LP.’ The statistics are staggering — and so is the toll on society. Throughout the world, roughly

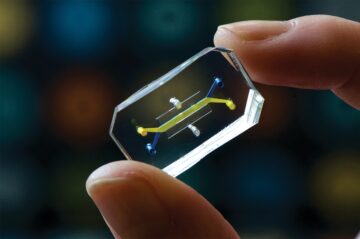

The statistics are staggering — and so is the toll on society. Throughout the world, roughly  The small plastic chip etched with channels is a synthetic human organ—and one vision of future drug safety testing. Inside, layers of human liver, epithelial, and immune cells line the tiny conduits, which feed them with bloodlike fluid and remove waste. The chip, made by the Boston-based biotech company Emulate Inc., could one day help researchers and pharmaceutical companies screen out candidate drugs that cause a condition known as drug-induced liver injury (DILI)—one of several types of liver toxicity that together

The small plastic chip etched with channels is a synthetic human organ—and one vision of future drug safety testing. Inside, layers of human liver, epithelial, and immune cells line the tiny conduits, which feed them with bloodlike fluid and remove waste. The chip, made by the Boston-based biotech company Emulate Inc., could one day help researchers and pharmaceutical companies screen out candidate drugs that cause a condition known as drug-induced liver injury (DILI)—one of several types of liver toxicity that together  We’ve all heard (some among us have preached) well-meaning sermons about the importance of amplifying marginalized voices in literary spaces. Yet despite good intentions—e.g., tropes of the “perceptive outsider” or “staunch individualist”—there remains a dearth of more fully rendered neurodiverse characters. One of our finest contemporary writers, Gary Shteyngart, is here to remedy that problem. Meet Vera Bradford-Shmulkin, the plucky, if often melancholy, 10-year-old protagonist of Shteyngart’s enchanting new novel, Vera, or Faith. An academic overachiever obsessed with language and a future career as “a woman in STEM,” Vera feels alienated from her classmates at her Manhattan magnet elementary. She struggles to calm her “monkey brain” and control her toe-walking and arm flaps, signature behaviors of mild autism, or what we used to categorize as Asperger’s syndrome. Shteyngart portrays these with compassion; his focus is on the potential of the “outsider” as a gifted truth-teller. Far from a subject of pity, Vera is a wise and feeling guide—like a 10-year-old Virgil, shepherding us through the novel’s netherworld of tormented souls while contending with her own angsts.

We’ve all heard (some among us have preached) well-meaning sermons about the importance of amplifying marginalized voices in literary spaces. Yet despite good intentions—e.g., tropes of the “perceptive outsider” or “staunch individualist”—there remains a dearth of more fully rendered neurodiverse characters. One of our finest contemporary writers, Gary Shteyngart, is here to remedy that problem. Meet Vera Bradford-Shmulkin, the plucky, if often melancholy, 10-year-old protagonist of Shteyngart’s enchanting new novel, Vera, or Faith. An academic overachiever obsessed with language and a future career as “a woman in STEM,” Vera feels alienated from her classmates at her Manhattan magnet elementary. She struggles to calm her “monkey brain” and control her toe-walking and arm flaps, signature behaviors of mild autism, or what we used to categorize as Asperger’s syndrome. Shteyngart portrays these with compassion; his focus is on the potential of the “outsider” as a gifted truth-teller. Far from a subject of pity, Vera is a wise and feeling guide—like a 10-year-old Virgil, shepherding us through the novel’s netherworld of tormented souls while contending with her own angsts. Ecologist Mark Vellend’s thesis is that to understand the world, “physics and evolution are the only two things you need”.

Ecologist Mark Vellend’s thesis is that to understand the world, “physics and evolution are the only two things you need”.  Because of climate, the North farmed crops like wheat and barley that required very little work, and that work was easy to automate. This tended to make farmers independent, incentivize industrialization for the machinery, and push settlers west very fast, as they weren’t as limited by labor needs.

Because of climate, the North farmed crops like wheat and barley that required very little work, and that work was easy to automate. This tended to make farmers independent, incentivize industrialization for the machinery, and push settlers west very fast, as they weren’t as limited by labor needs. Kaputt

Kaputt