Justin E. H. Smith in Unherd:

Justin E. H. Smith in Unherd:

Among the most ingenious moments in Kraftwerk’s admirable oeuvre is the point in 1981’s “Pocket Calculator” when a human voice self-contentedly sings: “By pressing down a special key / It plays a little melody.” The melody follows in confirmation. The genius here seems to lie in the blunt honesty of the singer, owning up to the contemporary condition of music as an art form that has largely been outsourced to machines. It’s not that the German electronic band invented the technology, nor that they were the first to make use of it. They are simply among the first to figure out how to elevate it to self-awareness, and to press it into a gesture of timely irony and potentially timeless beauty; that is, to make art out of it.

The little melody in question is of course a pre-set. Its sequence of notes is planned in advance, and once the key is pressed, the machine may be relied upon to do only the thing it has been programmed to do. The melody, it goes without saying, is no Bach fugue. It is simple, naïve, kind of dumb; and within the context of the song, it is utterly compelling.

Several conditions — technological, cultural, historical — had to fall into place in order for this melodic interlude, with its verbal introduction, to come across to the critical listener as an expression of genius. All of these conditions might be cited in response to any philistine tempted to declare, of the pressing down of that special key, that “I could have done that too”. We are used to hearing such petulant ressentiment, especially in connection with the 20th-century avant-garde in the figurative arts: “I could have entered a urinal in an exhibition, too”; “I could have painted an all-white monochrome, too”; etc. The simplest response is, “Yes, but you didn’t”.

More here.

Escape behavior offers useful insight into the brain’s inner workings because it engages nervous system networks that originated in the early days of evolution. “From the moment there was life, there were species predating on each other and therefore strong evolutionary pressure for evolving behaviors to avoid predators,” says neuroscientist Tiago Branco of University College London.

Escape behavior offers useful insight into the brain’s inner workings because it engages nervous system networks that originated in the early days of evolution. “From the moment there was life, there were species predating on each other and therefore strong evolutionary pressure for evolving behaviors to avoid predators,” says neuroscientist Tiago Branco of University College London.

We should expunge, forever, the epithet ‘precolonial’ or any of its cognates from all aspects of the study of Africa and its phenomena. We should banish title phrases, names and characterisations of reality and ideas containing the word.

We should expunge, forever, the epithet ‘precolonial’ or any of its cognates from all aspects of the study of Africa and its phenomena. We should banish title phrases, names and characterisations of reality and ideas containing the word. The game is rigged. It is rigged like capitalism is rigged. There is no puppet master, no conspiracy, only a field where advantages, to begin with, are distributed unequally. You can beat the long odds, but you have long odds to beat; a team of scholars has been working for almost 10 years to detail exactly how the rigging works. Juliana Spahr and Stephanie Young, later joined by Claire Grossman, began by noticing that poetry readings they regularly attended were held in “mainly white rooms.” They wanted to know why. To find out, they would need to widen their purview. The wider they went, the hungrier they became to understand who gets to succeed as a writer in the United States today. They wanted to reveal the system, to see all of it.

The game is rigged. It is rigged like capitalism is rigged. There is no puppet master, no conspiracy, only a field where advantages, to begin with, are distributed unequally. You can beat the long odds, but you have long odds to beat; a team of scholars has been working for almost 10 years to detail exactly how the rigging works. Juliana Spahr and Stephanie Young, later joined by Claire Grossman, began by noticing that poetry readings they regularly attended were held in “mainly white rooms.” They wanted to know why. To find out, they would need to widen their purview. The wider they went, the hungrier they became to understand who gets to succeed as a writer in the United States today. They wanted to reveal the system, to see all of it. I

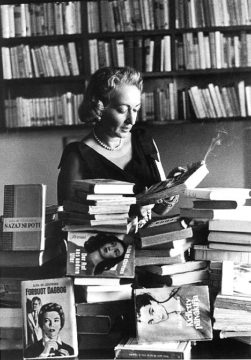

I The field is all but clear now, and it seems safe to say that the two most important long-form journalists this country produced in the second half of the last century were Joan Didion and Janet Malcolm. Their differences are more evident than their similarities: the cold Los Angeles burn of Didion’s work, the measured New York ambiguity of Malcolm’s. Still, perhaps it’s no accident that both were white women, marginalized by definition, yet not so strictly that it prevented either from slipping into the mainstream as witness, as recorder. Both were born in 1934, and both died in 2021. A world goes with them.

The field is all but clear now, and it seems safe to say that the two most important long-form journalists this country produced in the second half of the last century were Joan Didion and Janet Malcolm. Their differences are more evident than their similarities: the cold Los Angeles burn of Didion’s work, the measured New York ambiguity of Malcolm’s. Still, perhaps it’s no accident that both were white women, marginalized by definition, yet not so strictly that it prevented either from slipping into the mainstream as witness, as recorder. Both were born in 1934, and both died in 2021. A world goes with them. Herman Mark Schwartz in Progressive International:

Herman Mark Schwartz in Progressive International: Justin E. H. Smith in Unherd:

Justin E. H. Smith in Unherd: Jeremy Walton in Sidecar (image credit: Stable Diffusion):

Jeremy Walton in Sidecar (image credit: Stable Diffusion): Daniel Driscoll in Phenomenal World’s Polycrisis (image credit: Stable Diffusion):

Daniel Driscoll in Phenomenal World’s Polycrisis (image credit: Stable Diffusion): T

T Rome, 1950: The diary begins innocently enough, with the name of its owner, Valeria Cossati, written in a neat script.

Rome, 1950: The diary begins innocently enough, with the name of its owner, Valeria Cossati, written in a neat script. When British brain surgeon Henry Marsh sat down beside his patient’s bed following surgery, the bad news he was about to deliver stemmed from his own mistake. The man had a trapped nerve in his arm that required an operation – but after making a midline incision in his neck,

When British brain surgeon Henry Marsh sat down beside his patient’s bed following surgery, the bad news he was about to deliver stemmed from his own mistake. The man had a trapped nerve in his arm that required an operation – but after making a midline incision in his neck,  Animals that produce many offspring tend to have short lives, while less prolific species tend to live longer. Cockroaches lay hundreds of eggs while living less than a year. Mice have dozens of babies during their year or two of life. Humpback whales produce only one calf every two or three years and live for decades. The rule of thumb seems to reflect evolutionary strategies that channel nutritional resources either into reproducing quickly or into growing more robust for a long-term advantage.

Animals that produce many offspring tend to have short lives, while less prolific species tend to live longer. Cockroaches lay hundreds of eggs while living less than a year. Mice have dozens of babies during their year or two of life. Humpback whales produce only one calf every two or three years and live for decades. The rule of thumb seems to reflect evolutionary strategies that channel nutritional resources either into reproducing quickly or into growing more robust for a long-term advantage. A carefully administered and properly controlled dosage of a hallucinogen, their studies attest, can accomplish in a single, not-to-be-repeated session what years of psychotherapy and regimens of antidepressant medications often fail to achieve.

A carefully administered and properly controlled dosage of a hallucinogen, their studies attest, can accomplish in a single, not-to-be-repeated session what years of psychotherapy and regimens of antidepressant medications often fail to achieve.