Dennis Overbye in The New York Times:

The future belongs to those who prepare for it, as scientists who petition federal agencies like NASA and the Department of Energy for research funds know all too well. The price of big-ticket instruments like a space telescope or particle accelerator can be as high as $10 billion.

The future belongs to those who prepare for it, as scientists who petition federal agencies like NASA and the Department of Energy for research funds know all too well. The price of big-ticket instruments like a space telescope or particle accelerator can be as high as $10 billion.

And so this past June, the physics community began to consider what they want to do next, and why.

That is the mandate of a committee appointed by the National Academy of Sciences, called Elementary Particle Physics: Progress and Promise. Sharing the chairmanship are two prominent scientists: Maria Spiropulu, Shang-Yi Ch’en Professor of Physics at the California Institute of Technology, and the cosmologist Michael Turner, an emeritus professor at the University of Chicago, the former assistant director of the National Science Foundation and former president of the American Physical Society.

More here.

Certainly, Ferber’s approach—critical but forgiving to individual people and America at large—stems largely from who she was as a person and the way in which she moved through the world as a feme sole. A firsthand expert on the old maid lifestyle herself, Ferber was never known to have had a romantic or sexual relationship. But far from being a sad, sere figure whom life was passing by, she was vibrant, indefatigable, witty, and successful, a member of the Algonquin Round Table in New York and a winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1925 for So Big, another wonderful Chicago novel. She saw that book eventually adapted into one silent picture and two talkies. Her 1926 novel Show Boat was made into the famous 1927 musical, and Cimarron (1930), Giant (1952), and The Ice Palace (1958) were all adapted into films as well. When

Certainly, Ferber’s approach—critical but forgiving to individual people and America at large—stems largely from who she was as a person and the way in which she moved through the world as a feme sole. A firsthand expert on the old maid lifestyle herself, Ferber was never known to have had a romantic or sexual relationship. But far from being a sad, sere figure whom life was passing by, she was vibrant, indefatigable, witty, and successful, a member of the Algonquin Round Table in New York and a winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1925 for So Big, another wonderful Chicago novel. She saw that book eventually adapted into one silent picture and two talkies. Her 1926 novel Show Boat was made into the famous 1927 musical, and Cimarron (1930), Giant (1952), and The Ice Palace (1958) were all adapted into films as well. When  IF A SINGLE QUESTION is guiding for our understanding of Manet’s art during the first half of the 1860s, it is this: What are we to make of the numerous references in his paintings of those years to the work of the great painters of the past? A few of Manet’s historically aware contemporaries recognized explicit references to past art in some of his important pictures of that period; and by the time he died his admirers tended to play down the paintings of the first half of the sixties, if not of the entire decade, largely because of what had come to seem their overall dependence on the Old Masters. By 1912 Blanche could claim, in a kind of hyperbole, that it was impossible to find two paintings in Manet’s oeuvre that had not been inspired by other paintings, old or modern. But it has been chiefly since the retrospective exhibition of 1932 that historians investigating the sources of Manet’s art have come to realize concretely the extent to which it is based upon specific paintings, engravings after paintings, and original prints by artists who preceded him. It is now clear, for example, that most of the important pictures of the sixties depend either wholly or in part on works by Velasquez, Goya, Rubens, Van Dyck, Raphael, Titian, Giorgione, Veronese, Le Nain, Watteau, Chardin, Courbet . . . This by itself is an extraordinary fact, one that must be accounted for if Manet’s enterprise is to be made intelligible.

IF A SINGLE QUESTION is guiding for our understanding of Manet’s art during the first half of the 1860s, it is this: What are we to make of the numerous references in his paintings of those years to the work of the great painters of the past? A few of Manet’s historically aware contemporaries recognized explicit references to past art in some of his important pictures of that period; and by the time he died his admirers tended to play down the paintings of the first half of the sixties, if not of the entire decade, largely because of what had come to seem their overall dependence on the Old Masters. By 1912 Blanche could claim, in a kind of hyperbole, that it was impossible to find two paintings in Manet’s oeuvre that had not been inspired by other paintings, old or modern. But it has been chiefly since the retrospective exhibition of 1932 that historians investigating the sources of Manet’s art have come to realize concretely the extent to which it is based upon specific paintings, engravings after paintings, and original prints by artists who preceded him. It is now clear, for example, that most of the important pictures of the sixties depend either wholly or in part on works by Velasquez, Goya, Rubens, Van Dyck, Raphael, Titian, Giorgione, Veronese, Le Nain, Watteau, Chardin, Courbet . . . This by itself is an extraordinary fact, one that must be accounted for if Manet’s enterprise is to be made intelligible. Indeed, the

Indeed, the  The blue, fin, bowhead, gray, humpback, right and sperm whales are the largest animals alive today. In fact, the blue whale is the largest-known creature ever on Earth, topping even the biggest of the dinosaurs.

The blue, fin, bowhead, gray, humpback, right and sperm whales are the largest animals alive today. In fact, the blue whale is the largest-known creature ever on Earth, topping even the biggest of the dinosaurs. In late 1968, the train and bus stations of Chinese cities filled with sobbing adolescents and frightened parents. The authorities had decreed that teenagers – deployed by

In late 1968, the train and bus stations of Chinese cities filled with sobbing adolescents and frightened parents. The authorities had decreed that teenagers – deployed by  If the coconut symbolizes the natural bounty of the tropical zone in many people’s minds, it is often used to “explain” the human poverty frequently found in the zone. A common assumption in rich countries is that poor countries are poor because their people do not work hard. And given that most, if not all, poor countries are in the tropics, they often attribute the lack of work ethic of the people in poor countries to the easy living that they supposedly get thanks to the bounty of the tropics. In the tropics, it is said, food grows everywhere (bananas, coconuts, mangoes—the usual imagery goes), while the high temperature means that people don’t need sturdy shelter or much clothing.

If the coconut symbolizes the natural bounty of the tropical zone in many people’s minds, it is often used to “explain” the human poverty frequently found in the zone. A common assumption in rich countries is that poor countries are poor because their people do not work hard. And given that most, if not all, poor countries are in the tropics, they often attribute the lack of work ethic of the people in poor countries to the easy living that they supposedly get thanks to the bounty of the tropics. In the tropics, it is said, food grows everywhere (bananas, coconuts, mangoes—the usual imagery goes), while the high temperature means that people don’t need sturdy shelter or much clothing.

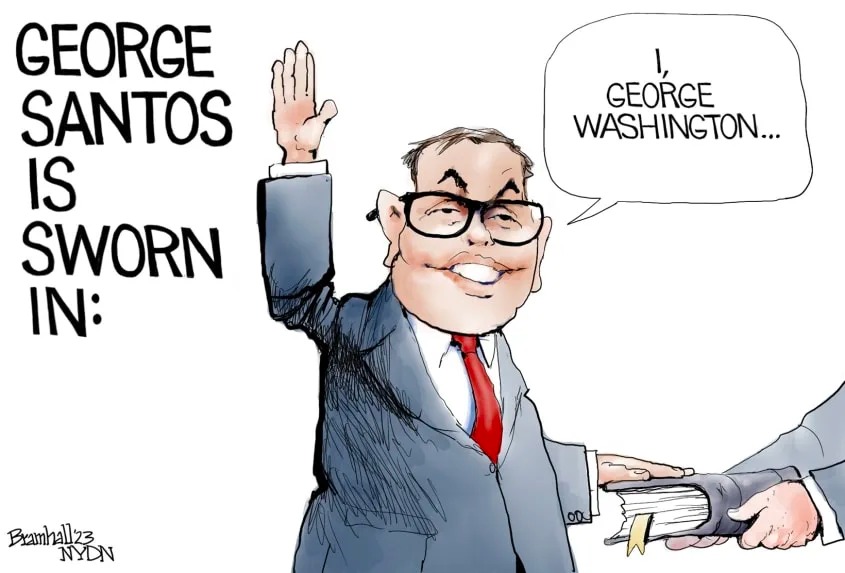

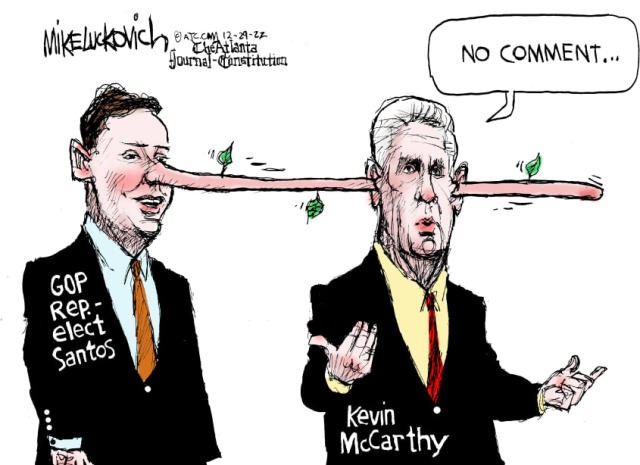

WASHINGTON — It’s not a pretty sight when pols lose power. They wilt, they crumple, they cling to the vestiges, they mourn their vanished entourage and perks. How can their day in the sun be over? One minute they’re running the world and the next, they’re in the room where it doesn’t happen.

WASHINGTON — It’s not a pretty sight when pols lose power. They wilt, they crumple, they cling to the vestiges, they mourn their vanished entourage and perks. How can their day in the sun be over? One minute they’re running the world and the next, they’re in the room where it doesn’t happen. Paul Dicken in LA Review of Books:

Paul Dicken in LA Review of Books: Merve Emre in The New Yorker:

Merve Emre in The New Yorker: Justin Vassallo in Phenomenal World:

Justin Vassallo in Phenomenal World: Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar:

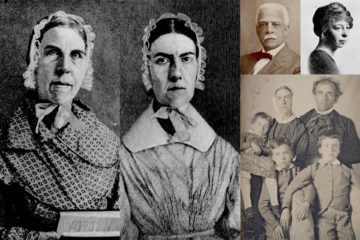

Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar: Born at the turn of the 19th century, the Grimke sisters, Angelina and Sarah, left their slaveholding family in Charleston, S.C., as young adults and made new lives for themselves as abolitionists in the North. In 1838, Angelina became the first woman to speak before a legislative body in the United States when she addressed the Massachusetts Legislature and called for an immediate end to slavery. In the same speech, she made a passionate case for women’s rights, insisting that women belonged at the center of major political debates. “Are we aliens because we are women?” she asked. “Are we bereft of citizenship because we are the mothers, wives and daughters of a mighty people?”

Born at the turn of the 19th century, the Grimke sisters, Angelina and Sarah, left their slaveholding family in Charleston, S.C., as young adults and made new lives for themselves as abolitionists in the North. In 1838, Angelina became the first woman to speak before a legislative body in the United States when she addressed the Massachusetts Legislature and called for an immediate end to slavery. In the same speech, she made a passionate case for women’s rights, insisting that women belonged at the center of major political debates. “Are we aliens because we are women?” she asked. “Are we bereft of citizenship because we are the mothers, wives and daughters of a mighty people?” This is not a thing anymore.

This is not a thing anymore.