Category: Recommended Reading

An Epicurean Guide To Happiness

Julian Baggini at The Guardian:

No one today would dream of practising the physics, medicine or biology of the ancient Greeks. But their thoughts on how to live remain perennially inspiring. Plato, Aristotle and the Stoics have all had their 21st-century evangelists. Now it is Epicurus’s turn, and his advocate is American philosopher Emily A Austin.

No one today would dream of practising the physics, medicine or biology of the ancient Greeks. But their thoughts on how to live remain perennially inspiring. Plato, Aristotle and the Stoics have all had their 21st-century evangelists. Now it is Epicurus’s turn, and his advocate is American philosopher Emily A Austin.

Living for Pleasure is likely to evoke feelings of deja vu. One reason why “ancient wisdom” is so enduring is that most thinkers came to very similar conclusions on certain key points. Do not be seduced by the shallow temptations of wealth or glory. Pursue what is of real value to you, not what society tells you is most important. Be the sovereign of your desires, not a slave to them. Do not be scared of death, since only the superstitious fear divine punishment.

more here.

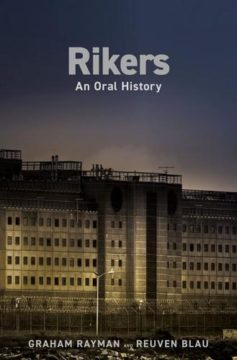

An Oral History of Rikers Island

Dwight Garner at the NY Times:

One of the takeaways of “Rikers: An Oral History,” a new book by the journalists Graham Rayman and Reuven Blau, is the shock inmates feel upon entering this run-down and lawless prison for the first time. It’s not just the sense of peril, the reek of toilets and cramped quarters, and the nullity of the concept of presumption of innocence — it’s an awareness, as one interviewee puts it, that “nobody cared and nobody was watching.”

One of the takeaways of “Rikers: An Oral History,” a new book by the journalists Graham Rayman and Reuven Blau, is the shock inmates feel upon entering this run-down and lawless prison for the first time. It’s not just the sense of peril, the reek of toilets and cramped quarters, and the nullity of the concept of presumption of innocence — it’s an awareness, as one interviewee puts it, that “nobody cared and nobody was watching.”

Alongside that shock, the rapper Fat Joe tells the authors, is the awareness that, if you grew up in the projects and attended the public schools, you know this place. “I’m willing to bet that the same architect designed all three things,” he says, having visited friends at the jail complex when he was growing up. “I’m telling you I was born in Rikers.”

more here.

Saturday Poem

Quarantine

In the worst hour of the worst season

of the worst year of a whole people

a man set out from the workhouse with his wife.

He was walking—they were both walking—north.

She was sick with famine fever and could not keep up.

He lifted her and put her on his back.

He walked like that west and west and north.

Until at nightfall under freezing stars they arrived.

In the morning they were both found dead.

Of cold. Of hunger. Of the toxins of a whole history.

But her feet were held against his breastbone.

The last heat of his flesh was his last gift to her.

Let no love poem ever come to this threshold.

There is no place here for the inexact

praise of the easy graces and sensuality of the body.

There is only time for this merciless inventory:

Their death together in the winter of 1847.

Also what they suffered. How they lived.

And what there is between a man and woman.

And in which darkness it can best be proved.

by Eavan Boland – 1944-2020

from New Collected Poems by Eavan Boland

W.W. Norton, 2008

What Monks Can Teach Us About Paying Attention

Casey Cep in The New Yorker:

Who was the monkiest monk of them all? One candidate is Simeon Stylites, who lived alone atop a pillar near Aleppo for at least thirty-five years. Another is Macarius of Alexandria, who pursued his spiritual disciplines for twenty days straight without sleeping. He was perhaps outdone by Caluppa, who never stopped praying, even when snakes filled his cave, slithering under his feet and falling from the ceiling. And then there’s Pachomius, who not only managed to maintain his focus on God while living with other monks but also ignored the demons that paraded about his room like soldiers, rattled his walls like an earthquake, and then, in a last-ditch effort to distract him, turned into scantily clad women. Not that women were only distractions. They, too, could have formidable attention spans—like the virgin Sarah, who lived next to a river for sixty years without ever looking at it.

Who was the monkiest monk of them all? One candidate is Simeon Stylites, who lived alone atop a pillar near Aleppo for at least thirty-five years. Another is Macarius of Alexandria, who pursued his spiritual disciplines for twenty days straight without sleeping. He was perhaps outdone by Caluppa, who never stopped praying, even when snakes filled his cave, slithering under his feet and falling from the ceiling. And then there’s Pachomius, who not only managed to maintain his focus on God while living with other monks but also ignored the demons that paraded about his room like soldiers, rattled his walls like an earthquake, and then, in a last-ditch effort to distract him, turned into scantily clad women. Not that women were only distractions. They, too, could have formidable attention spans—like the virgin Sarah, who lived next to a river for sixty years without ever looking at it.

These all-stars of attention are just a few of the monks who populate Jamie Kreiner’s new book, “The Wandering Mind: What Medieval Monks Tell Us About Distraction” (Liveright). More specifically, they are the exceptions: most of their brethren, like most of us, were terrible at paying attention.

More here.

Think Screens Stole Our Attention? Medieval Monks Were Distracted Too

Jennifer Szalai in The New York Times:

Among the resources that have been plundered by modern technology, the ruins of our attention have commanded a lot of attention. We can’t focus anymore. Getting any “deep work” done requires formidable willpower or a broken modem. Reading has degenerated into skimming and scrolling. The only real way out is to adopt a meditation practice and cultivate a monkish existence. But in actual historical fact, a life of prayer and seclusion has never meant a life without distraction. As Jamie Kreiner puts it in her new book, “The Wandering Mind,” the monks of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages (around A.D. 300 to 900) struggled mightily with attention. Connecting one’s mind to God was no easy task. The goal was “clearsighted calm above the chaos,” Kreiner writes. John of Dalyatha, an eighth-century monk who lived in what is now northern Iraq, lamented in a letter to his brother, “All I do is eat, sleep, drink and be negligent.”

Among the resources that have been plundered by modern technology, the ruins of our attention have commanded a lot of attention. We can’t focus anymore. Getting any “deep work” done requires formidable willpower or a broken modem. Reading has degenerated into skimming and scrolling. The only real way out is to adopt a meditation practice and cultivate a monkish existence. But in actual historical fact, a life of prayer and seclusion has never meant a life without distraction. As Jamie Kreiner puts it in her new book, “The Wandering Mind,” the monks of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages (around A.D. 300 to 900) struggled mightily with attention. Connecting one’s mind to God was no easy task. The goal was “clearsighted calm above the chaos,” Kreiner writes. John of Dalyatha, an eighth-century monk who lived in what is now northern Iraq, lamented in a letter to his brother, “All I do is eat, sleep, drink and be negligent.”

Kreiner, a historian at the University of Georgia, organizes the book around the various sources of distraction that a Christian monk had to face, from “the world” to the smaller “community,” all the way down to “memory” and the “mind.” Abandoning the familiar and profane was only the first step in what would turn out to be an unrelenting process — though as Kreiner explains, many monks continued to reside at home, committing themselves to lives of renunciation and prayer. For the monks who did leave, there were any number of possibilities beyond the confines of a monastery, which could pose its own distractions. Caves and deserts were obvious alternatives. Macedonius “the Pit” was partial to holes in the ground. Frange dwelled in a pharaoh’s tomb. Simeon, a “stylite,” lived on top of a pillar.

More here.

Friday, January 27, 2023

Bill Gates: The surprising key to a clean energy future

Bill Gates in his own blog:

The United States has made remarkable progress over the last two years toward a future where every home is powered by clean energy. Thanks in part to historic federal investments, we’re on a path to use more clean electricity sources than ever before—including wind, solar, nuclear, and geothermal energy—which would reduce household costs, cut pollution, and diversify our energy supply so we’re not dependent on any one thing.

The United States has made remarkable progress over the last two years toward a future where every home is powered by clean energy. Thanks in part to historic federal investments, we’re on a path to use more clean electricity sources than ever before—including wind, solar, nuclear, and geothermal energy—which would reduce household costs, cut pollution, and diversify our energy supply so we’re not dependent on any one thing.

But to take advantage of this opportunity, we need to first bring our grid into the 21st century. (This is an issue in other places around the world, too, but I’m going to focus on the U.S. here.) The way we move electricity around in this country just isn’t designed to meet modern energy needs.

More here.

What time is it on the Moon?

Elizabeth Gibney in Nature:

The Moon doesn’t currently have an independent time. Each lunar mission uses its own timescale that is linked, through its handlers on Earth, to coordinated universal time, or UTc — the standard against which the planet’s clocks are set. But this method is relatively imprecise and spacecraft exploring the Moon don’t synchronize the time with each other. The approach works when the Moon hosts a handful of independent missions, but it will be a problem when there are multiple craft working together. Space agencies will also want to track them using satellite navigation, which relies on precise timing signals.

The Moon doesn’t currently have an independent time. Each lunar mission uses its own timescale that is linked, through its handlers on Earth, to coordinated universal time, or UTc — the standard against which the planet’s clocks are set. But this method is relatively imprecise and spacecraft exploring the Moon don’t synchronize the time with each other. The approach works when the Moon hosts a handful of independent missions, but it will be a problem when there are multiple craft working together. Space agencies will also want to track them using satellite navigation, which relies on precise timing signals.

It’s not obvious what form a universal lunar time would take.

More here.

Endless Flight: The Life of Joseph Roth

Katrina Goldstone at the Dublin Review of Books:

When Joseph Roth died in penury in Paris in 1939, he left little behind. No trace of his collection of penknives, watches, walking canes and clothes bought for him by Stefan Zweig. The knives had been gathered to protect himself from both imagined and very real enemies. Soon after war’s end, his cousin visited one of his translators, Blanche Gidon, and was presented with “an old worn out coupe case”. Within it was a treasure trove ‑ some manuscripts, never published in his lifetime, books and letters. Throughout the long dark night of Nazi occupation Gidon had kept it hidden under the bed of the concierge. There have been other custodians of Roth’s reputation along the way, Hermann Kesten, a friend, and Roth’s translator, Michael Hofmann. Yet his literary significance was often ignored. Roth had been an early and vocal critic of Hitlerism. His masterpiece, The Radetsky March, had been among the first books committed for incendiary destruction when the Nazis came to power. Yet, as this magisterial biography by Kieron Pim shows, the phrase “man of many contradictions” is scarcely fit for purpose when trying to grapple with the complex contrarian Moses Joseph Roth. If Joseph Roth hadn’t been born, he’d have been invented, as a picaresque character in a novel probably by an impoverished disillusioned Mitteleuropa writer fleeing from Nazi Germany for his life.

When Joseph Roth died in penury in Paris in 1939, he left little behind. No trace of his collection of penknives, watches, walking canes and clothes bought for him by Stefan Zweig. The knives had been gathered to protect himself from both imagined and very real enemies. Soon after war’s end, his cousin visited one of his translators, Blanche Gidon, and was presented with “an old worn out coupe case”. Within it was a treasure trove ‑ some manuscripts, never published in his lifetime, books and letters. Throughout the long dark night of Nazi occupation Gidon had kept it hidden under the bed of the concierge. There have been other custodians of Roth’s reputation along the way, Hermann Kesten, a friend, and Roth’s translator, Michael Hofmann. Yet his literary significance was often ignored. Roth had been an early and vocal critic of Hitlerism. His masterpiece, The Radetsky March, had been among the first books committed for incendiary destruction when the Nazis came to power. Yet, as this magisterial biography by Kieron Pim shows, the phrase “man of many contradictions” is scarcely fit for purpose when trying to grapple with the complex contrarian Moses Joseph Roth. If Joseph Roth hadn’t been born, he’d have been invented, as a picaresque character in a novel probably by an impoverished disillusioned Mitteleuropa writer fleeing from Nazi Germany for his life.

more here.

Wednesday’s Curdled Beauty

Quinn Moreland at Pitchfork:

The most ambitious moment on Rat Saw God arrives via the eight-and-a-half-minute opus “Bull Believer.” While Hartzman prefers to keep the specifics private, it’s a song about death and desperation told through images of blood, roadside monuments, and a bull with one foot in the grave.

The most ambitious moment on Rat Saw God arrives via the eight-and-a-half-minute opus “Bull Believer.” While Hartzman prefers to keep the specifics private, it’s a song about death and desperation told through images of blood, roadside monuments, and a bull with one foot in the grave.

Hartzman knew that she wanted the track to conclude with a guttural outcry, but she was also a little frightened by what might emerge from her body when she opened her mouth. “I was too self-conscious to try in practice,” she explains. “I imagined driving into the middle of nowhere and trying to scream, but even then I was worried someone would hear me and be worried.” At the studio, while her bandmates played Tetris downstairs, Hartzman channeled the agony of the past until it erupted out of her in a torrent of screams, nervous laughter, and a single phrase pulled from Mortal Kombat: “Finish him!”

more here.

Wednesday – Bull Believer

Ready, set, share! making data freely available

Kaiser and Brainard in Science:

Physiologist Alejandro Caicedo of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine is preparing a grant proposal to the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). He is feeling unusually stressed because of a new requirement that takes effect today. Along with his research idea, to study why islet cells in the pancreas stop making insulin in people with diabetes, he will be required to submit a plan for managing the data the project produces and sharing them in public repositories.

Physiologist Alejandro Caicedo of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine is preparing a grant proposal to the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). He is feeling unusually stressed because of a new requirement that takes effect today. Along with his research idea, to study why islet cells in the pancreas stop making insulin in people with diabetes, he will be required to submit a plan for managing the data the project produces and sharing them in public repositories.

For his lab, that’s a daunting task. Unlike neuroscience or genomics, Caicedo’s field has no common platforms or standards for storing and sharing the kinds of data his lab generates, such as videos of pancreatic islet cells responding to a glucose stimulus. The “humongous” raw imaging files are currently stored in an on-campus database, notes Julia Panzer, a postdoctoral researcher in the lab. To protect patient privacy, the database is secured and not designed to provide access to outsiders. Sharing the data will mean uploading them somewhere else.

More here.

Could the “Chinese Century” Belong to India?

Pranab Bardhan in Project Syndicate:

I think the century will probably not belong to China or India – or any country, for that matter. Chinese achievements in the last few decades have been phenomenal, but it is now experiencing a palpable – and expected – slowdown. And while international financial media have been hyping the arrival of “India’s moment,” a cold look at the facts suggests that such assessments are premature at best.

I think the century will probably not belong to China or India – or any country, for that matter. Chinese achievements in the last few decades have been phenomenal, but it is now experiencing a palpable – and expected – slowdown. And while international financial media have been hyping the arrival of “India’s moment,” a cold look at the facts suggests that such assessments are premature at best.

A key reason for this is demographic. Yes, India has most likely already surpassed China as the world’s largest country by population, and its youth bulge is substantial. But far from delivering a “demographic dividend,” India’s relatively young population may turn out to be a liability, as the country struggles to generate sufficient productive employment.

More here.

Benedict Cumberbatch reads a hilarious letter of apology to a hotel

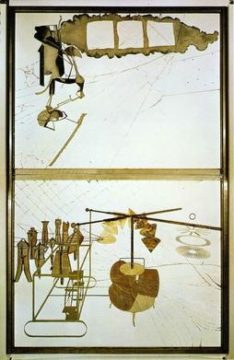

The artist Marcel Duchamp — 1/27/23

From Delancey Place:

“Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), the younger brother of the sculptor Duchamp-Villon, was perhaps the most stimulating intellectual to be concerned with the visual arts in the twentieth century — ironic, witty and penetrating. He was also a born anarchist. Like his brother, he began (after some exploratory years in various current styles) with a dynamic Futurist version of Cubism, of which his painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 is the best known example. It caused a scandal at the famous Armory Show of modern art in New York in 1913. Duchamp’s ready-mades are everyday manufactured objects converted into works of art simply by the artist’s act of choosing them. Duchamp did nothing to them except present them for contemplation as ‘art’. They represent in many ways the most iconoclastic gesture that any artist has ever made — a gesture of total rejection and revolt against accepted artistic canons. For by reducing the creative act simply to one of choice ‘ready-mades’ discredit the ‘work of art’ and the taste, skill, craftsmanship — not to mention any higher artistic values — that it traditionally embodies. Duchamp insisted again and again that his ‘choice of these ready-mades was never dictated by an aesthetic delectation. The choice was based on a reaction of visual indifference, with at the same time a total absence of good or bad taste, in fact a complete anaesthesia.’

“Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), the younger brother of the sculptor Duchamp-Villon, was perhaps the most stimulating intellectual to be concerned with the visual arts in the twentieth century — ironic, witty and penetrating. He was also a born anarchist. Like his brother, he began (after some exploratory years in various current styles) with a dynamic Futurist version of Cubism, of which his painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 is the best known example. It caused a scandal at the famous Armory Show of modern art in New York in 1913. Duchamp’s ready-mades are everyday manufactured objects converted into works of art simply by the artist’s act of choosing them. Duchamp did nothing to them except present them for contemplation as ‘art’. They represent in many ways the most iconoclastic gesture that any artist has ever made — a gesture of total rejection and revolt against accepted artistic canons. For by reducing the creative act simply to one of choice ‘ready-mades’ discredit the ‘work of art’ and the taste, skill, craftsmanship — not to mention any higher artistic values — that it traditionally embodies. Duchamp insisted again and again that his ‘choice of these ready-mades was never dictated by an aesthetic delectation. The choice was based on a reaction of visual indifference, with at the same time a total absence of good or bad taste, in fact a complete anaesthesia.’

More here.

Friday Poem

Main Street: Tilton, New Hampshire

I waited in the car while he

went into the small old-fashioned grocery

for a wedge of cheddar.

Late summer, Friday afternoon.

A mother and child walked past

trading mock blows

with paper bags full of —what—

maybe new clothes for school.

They turned the corner by the Laundromat,

and finally even the heel

of the girl’s rubber flip-flop

passed from sight.

Across the street a blue pickup, noisy,

with some kind of homemade wooden

scaffolding in the bed pulled

close to the curb. A man got out

and entered the bank . . .

………………………………….. A woman sat

in the cab, dabbing her face

with tissue. She might have been weeping,

but it was hot and still,

and maybe she wasn’t weeping at all.

Through time and space we came

to Main Street—three days before

Labor Day, 1984, 4:47 in the afternoon;

and then that moment passed, displaced

by others equally equivocal.

by Jane Kenyon

from Otherwise

Graywolf Press, 1997

Thursday, January 26, 2023

Is Sigrid Undset Underappreciated?

Ted Gioia at The Honest Broker:

Sigrid Undset was an unlikely literary star. Modernist themes were on the ascendancy in those days, but she wanted to write medieval romances. So at night, after work, she researched her subject, studying the sagas, old ballads, and chronicles of the Middle Ages.

Sigrid Undset was an unlikely literary star. Modernist themes were on the ascendancy in those days, but she wanted to write medieval romances. So at night, after work, she researched her subject, studying the sagas, old ballads, and chronicles of the Middle Ages.

You might say she lived in the past. Or in a fantasy world of her own creation. But Undset wanted to deal with these kinds of tales in a brutally realistic manner. She started writing stories where, in her own words, “everything that seems romantic from here—murder, violent episodes, etc. becomes ordinary—comes to life.” Her first novel was rejected by publishers. But her second book got noticed—and caused a scandal. The opening line announced: “I have been unfaithful to my husband.”

Against Copyediting

Do we really need copyediting? I don’t mean the basic clean-up that reverses typos, reinstates skipped words, and otherwise ensures that spelling and punctuation marks are as an author intends. Such copyediting makes an unintentionally “messy” manuscript easier to read, sure.

But the argument that texts ought to read “easily” slips too readily into justification for insisting a text working outside dominant Englishes better reflect the English of a dominant-culture reader—the kind of reader who might mirror the majority of those at the helm of the publishing industry, but not the kind of reader who reflects a potential readership (or writership) at large.

more here.

Salman Rushdie Has a New Book, and a Message: ‘Words Are the Only Victors’

Alexandra Alter and Elizabeth A. Harris in the New York Times:

In “Victory City,” a new novel by Salman Rushdie, a gifted storyteller and poet creates a new civilization through the sheer power of her imagination. Blessed by a goddess, she lives nearly 240 years, long enough to witness the rise and fall of her empire in southern India, but her lasting legacy is an epic poem.

In “Victory City,” a new novel by Salman Rushdie, a gifted storyteller and poet creates a new civilization through the sheer power of her imagination. Blessed by a goddess, she lives nearly 240 years, long enough to witness the rise and fall of her empire in southern India, but her lasting legacy is an epic poem.

“All that remains is this city of words,” the poet, Pampa Kampana, writes at the end of her epic, which she buries in a pot as a message for future generations. “Words are the only victors.”

Framed as the text of a rediscovered medieval Sanskrit epic, “Victory City” is about mythmaking, storytelling and the enduring power of language. It is also a triumphant return to the literary stage for Rushdie, who has been withdrawn from public life for months, recovering from a brutal stabbing while onstage during a cultural event in New York last year.

More here.

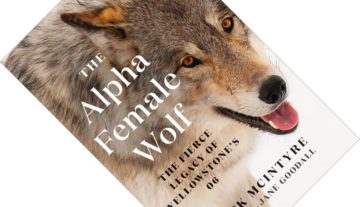

The Alpha Female Wolf at Yellowstone

Leon Vlieger at The Inquisitive Biologist:

The wolves reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park in 1995 are some of the best-studied mammals on the planet. Biological technician and park ranger Rick McIntyre has spent over two decades scrutinising their daily lives, venturing into the park every single day. Where his previous books focused on three notable alpha males, it is ultimately the females that call the shots and make the decisions with lasting consequences. This book is a long overdue recognition of the female wolf and continues this multigenerational saga.

The wolves reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park in 1995 are some of the best-studied mammals on the planet. Biological technician and park ranger Rick McIntyre has spent over two decades scrutinising their daily lives, venturing into the park every single day. Where his previous books focused on three notable alpha males, it is ultimately the females that call the shots and make the decisions with lasting consequences. This book is a long overdue recognition of the female wolf and continues this multigenerational saga.

If wolf 21, the subject of the second book, was the most famous male wolf in Yellowstone, then his granddaughter 06 (named after her year of birth, 2006) can safely be called the most famous female wolf. This fourth book picks up where the third book ended, covering the period 2009–2015. It tells 06’s life story, her untimely death, and the fate of one of her daughters.

More here.