Category: Recommended Reading

A New ‘Galaxy Brain’ Novel

Mark Athitakis at the LA Times:

“The Terraformers,” Newitz’s new novel, is an ingenious, galaxy-brain book. Set in the very distant future — circa AD 59,000 — it imagines human civilization evolving to the point where we can build new worlds and effectively process new types of creatures to steward them. Destry, a ranger monitoring a planet in progress in the novel’s early going, is a “hominin,” a human-like being who can live hundreds of years, and her fellow hominins peacefully cohabitate with different species. (Her steed is a flying, talking moose-like creature; naked mole rats abound.)

“The Terraformers,” Newitz’s new novel, is an ingenious, galaxy-brain book. Set in the very distant future — circa AD 59,000 — it imagines human civilization evolving to the point where we can build new worlds and effectively process new types of creatures to steward them. Destry, a ranger monitoring a planet in progress in the novel’s early going, is a “hominin,” a human-like being who can live hundreds of years, and her fellow hominins peacefully cohabitate with different species. (Her steed is a flying, talking moose-like creature; naked mole rats abound.)

But the management of Destry’s planet, Sask-E, is handled by a distant corporation, Verdance, and corporations haven’t evolved much at all. “The Terraformers” is thick with space travel, whiz-bang technology and radical re-envisioning of intra-species relationships, but Newitz’s concerns are earth-bound.

more here.

The Black Women Who Paved the Way for This Moment

Keisha Blain in The Atlantic:

In the 20th-century U.S., black-nationalist women—individuals who advocated for black liberation, economic self-sufficiency, racial pride, unity, and political self-determination—emerged as key political leaders on the local, national, and even international levels. When most black women in the U.S. did not have access to the vote, these women boldly confronted the hypocrisy of white America, often drawing upon their knowledge of history. And they did so in public spaces—in mass community meetings, at local parks, and on sidewalks. These women harnessed the power of their voices, passion, and the raw authenticity of their political message to rally black people across the nation and the globe.

In the 20th-century U.S., black-nationalist women—individuals who advocated for black liberation, economic self-sufficiency, racial pride, unity, and political self-determination—emerged as key political leaders on the local, national, and even international levels. When most black women in the U.S. did not have access to the vote, these women boldly confronted the hypocrisy of white America, often drawing upon their knowledge of history. And they did so in public spaces—in mass community meetings, at local parks, and on sidewalks. These women harnessed the power of their voices, passion, and the raw authenticity of their political message to rally black people across the nation and the globe.

In the early 1920s, Amy Ashwood Garvey, a co-founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, advocated for the rights and freedom of black people while standing on crowded street corners in Harlem. Using these public spaces as platforms to advance her political agenda, Ashwood held nothing back, imploring black people to resist white supremacy in all of its forms. On several occasions, the activist publicly recited poetry, including Paul Laurence Dunbar’s famous work “We Wear the Mask,” which emphasized the strategies black people employed to survive segregation, oppression, and daily degradation.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to Black History Month. The theme for 2023 is Black Resistance. Please send us anything you think is relevant for inclusion)

As Wallace Stevens Once Put It: Hi!

Elisa Gabbert in The New York Times:

Poker players have an expression for that moment when you look at your cards and discover you’ve been dealt the luckiest possible hand. It’s called “waking up with aces.” This reminds me of the way that the first lines of poems seem to come out of nowhere. It’s true for the poet, the lines just arriving, as if by dictation or angelic message — as Eliot writes in his essay on Blake, “The idea, of course, simply comes.” And it’s true for the reader, who can only have the same in medias res experience, encountering a line at the top of a page. There’s a shock to this unveiling. All the emails I get begin with some variation on “I hope this finds you well,” but a poem can begin in any kind of way. “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain.” “Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness.” There’s a Wallace Stevens poem that starts “Hi!”

Poker players have an expression for that moment when you look at your cards and discover you’ve been dealt the luckiest possible hand. It’s called “waking up with aces.” This reminds me of the way that the first lines of poems seem to come out of nowhere. It’s true for the poet, the lines just arriving, as if by dictation or angelic message — as Eliot writes in his essay on Blake, “The idea, of course, simply comes.” And it’s true for the reader, who can only have the same in medias res experience, encountering a line at the top of a page. There’s a shock to this unveiling. All the emails I get begin with some variation on “I hope this finds you well,” but a poem can begin in any kind of way. “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain.” “Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness.” There’s a Wallace Stevens poem that starts “Hi!”

“In the middle of our life’s journey,/I found myself in a dark wood.” That’s the most literal translation of the first two lines of Dante’s “Inferno.”

More here.

Saturday Poem

Poem in Which the Speaker Manages to Get a Quick Question in Edgewise as a List of Instructions is Dictated Regarding How Her Poems Ought to Be Written Via a Megaphone Located Above Her Headboard

We want you to write a poem in interest-free monthly installments.

A poem that is open 24 hours a day. A poem that includes wi-fi.

A poem made to be posted on Instagram.

A poem wearing cruelty-free make-up.

We want, naturally, a poem with no conservatives, a poem

low in saturated fat. A lactose-free, gluten-free, decaffeinated poem.

———————- —So, do you want a poem, or a soy venti chai latte?

We want a little word-making machine.

a music box without the ballerina

a remote control toy with batteries included.

The Noumenon Poem.

The Homeric Poem in Present Pluperfect.

The Phenomenal Bullet Poem.

The Multidisciplinary Poem, Incorporated.

themostpoeticwithoutbeingcatharticpoemeverwritten.com

We want an acrobatic, polyglot poem, a poem

with a T-shirt that reads [there is no poem b]

A poem that can be sung out loud. That pays its own way.

A poem without an expiration date. In other words, we want

a poem that counts backward from ninety-nine to zero

as instructed by an anesthesiologist. In other words, we want

a poem that will not wake up during surgery.

by Sara Uribe

from: Antígone González

© Translation: 2016, Tanya Huntington, J.D. Pluecker

Les Figues Press, , 2016

Friday, February 3, 2023

M. Night Shyamalan’s Fears and Redemptions

Adam Nayman in The New Yorker:

In M. Night Shyamalan’s new movie, “Knock at the Cabin,” a couple vacationing in rural Pennsylvania with their adopted daughter realize that they are not alone. A group of travellers is watching them from the trees and encroaching on the property. The films of Shyamalan are filled with such uninvited house guests. The big twist in “The Sixth Sense” (1999)—the one that turned its director into the most reliable American brand name in narrative trickery since O. Henry—finds its roots in a home invasion: a naked, emaciated mental patient appearing at Bruce Willis’s broken bedroom window. Intruders—be they human, monstrous, or extraterrestrial—figure into similarly unsettling set pieces in “Unbreakable,” “The Village,” and “The Visit.” Even Shyamalan’s flashy Will Smith vehicle, “After Earth” (2013), which has a crashing spaceship and futuristic monsters, pivots emotionally on a flashback featuring a breached family dwelling. The new film is an adaptation of a novel by Paul Tremblay, “The Cabin at the End of the World.” Shyamalan’s title lacks the apocalyptic overtones but has an added hint of playful urban-legend malevolence: that “knock” is the terrible sound of letting the wrong one in.

In M. Night Shyamalan’s new movie, “Knock at the Cabin,” a couple vacationing in rural Pennsylvania with their adopted daughter realize that they are not alone. A group of travellers is watching them from the trees and encroaching on the property. The films of Shyamalan are filled with such uninvited house guests. The big twist in “The Sixth Sense” (1999)—the one that turned its director into the most reliable American brand name in narrative trickery since O. Henry—finds its roots in a home invasion: a naked, emaciated mental patient appearing at Bruce Willis’s broken bedroom window. Intruders—be they human, monstrous, or extraterrestrial—figure into similarly unsettling set pieces in “Unbreakable,” “The Village,” and “The Visit.” Even Shyamalan’s flashy Will Smith vehicle, “After Earth” (2013), which has a crashing spaceship and futuristic monsters, pivots emotionally on a flashback featuring a breached family dwelling. The new film is an adaptation of a novel by Paul Tremblay, “The Cabin at the End of the World.” Shyamalan’s title lacks the apocalyptic overtones but has an added hint of playful urban-legend malevolence: that “knock” is the terrible sound of letting the wrong one in.

“These are just my fears, dude,” Shyamalan told me via Zoom recently. “I got married when I was twenty-two, and I’ve got three girls. We’re all incredibly close. My parents live nearby; my sister lives nearby. We have kept the family unit super tight, at the center of everything. So the fear of ‘Where is your daughter?,’ ‘She was supposed to be home,’ or ‘She didn’t call’—those are what start me writing. It’s working through these fears and then attaching them to some kind of supernatural manifestation.”

More here.

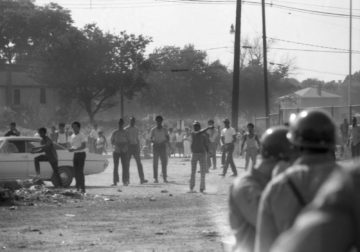

The Unknown History of Black Uprisings

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor in The New Yorker:

Black resistance took different forms, from Black residents pelting police with bricks and bottles to Black snipers shooting at police, with the purpose of driving them out of their communities. Black snipers, in particular, fulfilled political fantasies that demonized all forms of Black resistance as pathological and deserving of violent pacification. From 1967 to 1974, the number of police killed in the line of duty jumped from seventy-six to a hundred and thirty-two, the highest annual figure ever. But those totals were dwarfed by the number of young Black men killed by the police in the same period. Hinton reports that, between 1968 and 1974, “Black people were the victims of one in four police killings,” resulting in nearly a hundred Black men under twenty-five dying at the hands of police in each of those years. By comparison, today only one in ten people killed by police is Black, according to the Centers for Disease Control. (Hinton cites this figure but notes that it may represent underreporting.)

Black resistance took different forms, from Black residents pelting police with bricks and bottles to Black snipers shooting at police, with the purpose of driving them out of their communities. Black snipers, in particular, fulfilled political fantasies that demonized all forms of Black resistance as pathological and deserving of violent pacification. From 1967 to 1974, the number of police killed in the line of duty jumped from seventy-six to a hundred and thirty-two, the highest annual figure ever. But those totals were dwarfed by the number of young Black men killed by the police in the same period. Hinton reports that, between 1968 and 1974, “Black people were the victims of one in four police killings,” resulting in nearly a hundred Black men under twenty-five dying at the hands of police in each of those years. By comparison, today only one in ten people killed by police is Black, according to the Centers for Disease Control. (Hinton cites this figure but notes that it may represent underreporting.)

This cycle of abuse could not continue.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to Black History Month. The theme for 2023 is Black Resistance. Please send us anything you think is relevant for inclusion)

The Theology of Erich Pryzwara With Philip Gonzales

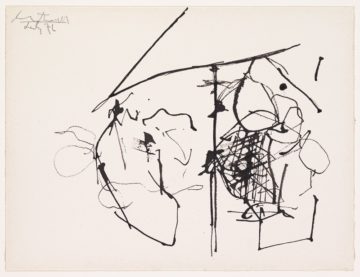

Robert Motherwell: The Drawings of a Painter

Katy Rogers at The Brooklyn Rail:

As I worked on this publication, I came to cherish Motherwell’s drawings more and more. Although they are the drawings of a painter, and drawing is not the medium he is principally known for, it is here, in his drawings, that we see his mind at work most clearly and most vividly. In his drawings, we can see the quintessence of depth and breadth of his work, from the abstracted figures of the 1940s to his purely automatist Lyric Suite (1965) and spare geometric “Open” series of the 1960s, to his luminous graphic responses to James Joyce during the 1980s. Although his drawings are related to—and sometimes provided the seeds for—his paintings, he revered drawing as a unique practice of its own, which had its own character and involved particular demands. For Motherwell, the medium was “the only thing in human existence that has precisely the same range of sensed feeling as people themselves do. And it is only when you think of the medium as having the same potential as another human being, that you begin to see the nature of the artist’s involvement.”

As I worked on this publication, I came to cherish Motherwell’s drawings more and more. Although they are the drawings of a painter, and drawing is not the medium he is principally known for, it is here, in his drawings, that we see his mind at work most clearly and most vividly. In his drawings, we can see the quintessence of depth and breadth of his work, from the abstracted figures of the 1940s to his purely automatist Lyric Suite (1965) and spare geometric “Open” series of the 1960s, to his luminous graphic responses to James Joyce during the 1980s. Although his drawings are related to—and sometimes provided the seeds for—his paintings, he revered drawing as a unique practice of its own, which had its own character and involved particular demands. For Motherwell, the medium was “the only thing in human existence that has precisely the same range of sensed feeling as people themselves do. And it is only when you think of the medium as having the same potential as another human being, that you begin to see the nature of the artist’s involvement.”

more here.

Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning

Jonathan Sumption at Literary Review:

Nigel Biggar retired a few months ago from the Regius Professorship of Moral and Pastoral Theology at Oxford. He is a notable figure in the world of moral philosophy, not only because of his distinguished academic career as an ethicist but also because of his persistent refusal to observe the conventional pieties which characterise so much that is written in his field.

Nigel Biggar retired a few months ago from the Regius Professorship of Moral and Pastoral Theology at Oxford. He is a notable figure in the world of moral philosophy, not only because of his distinguished academic career as an ethicist but also because of his persistent refusal to observe the conventional pieties which characterise so much that is written in his field.

There are few notions more pious or conventional than that empires are wicked and that the British Empire was unutterably and irredeemably so. In 2017, Biggar initiated the ‘Ethics and Empire’ project at Oxford, which sought to explore the factual and moral basis for this hostility. The project, its author and the university were at once denounced by other scholars in the field on the grounds that the very idea of balance in this area is unacceptable. To quote one of the most vocal antagonists, ‘any attempt to create a balance sheet of the good and evil of empire can’t be based on rigorous scholarship.’

more here.

Friday Poem

Giant

…. —Third Testimony: Ali

….. Butterfly, butterfly on the wall

….. Can’t you hear your country call?

Black man’s got no business being

both pretty and bold—with a right hook

as swift as his banter, his feet

a flurry of insults, disguised as dance.

There’s a war going on, but he’s having

none of it. He flicks those angry eyes,

then flings out a rhyme

quick as tossing a biscuit to a dog.

He’s our homegrown warrior, America’s

toffee-toned Titan; how dare he swagger

in the name of peace? No black man

strutting his minstrel ambitions

deserves these eloquent lips:

Swat him down, pin him to the mat!

On and on they mutter, hellbent on keeping

their own destiny unscathed

& brazenly manifest.

by Rita Dove

from Playlist for the Apocalypse

W.W. Norton and Company, 2021

Two People Who Don’t Have Cable TV Talk About How They Don’t Have Cable TV, And How Great That Makes Them

Michael Fontana at McSweeney’s:

A: I don’t even have cable anymore.

A: I don’t even have cable anymore.

B: Well, listen, good for you. I personally haven’t even owned a TV since 2008, but nevertheless, I am happy for you.

A: Did I say “anymore”? Because, in fact, I’ve never owned a TV. I am only vaguely aware of what a TV looks like. One time I just sat in front of a microwave, looking at it for a long period of time, wondering whether it would begin airing episodes of The White Lotus. It did not.

B: Yes, that makes sense. However, I do not know what a “The White Lotus” is. I am assuming it is a kind of flower. Because looking at flowers is the only kind of entertainment I need most days. If I absolutely must, I will watch TV on my laptop, with passwords shared by old boyfriends. Some of whom are now in long-term committed relationships and by now have adult children. Good for them.

More here.

Consciousness, Free Will, and the Limits of Science

Erik Hoel in his Substack, The Intrinsic Perspective:

For most of 2022 I was quietly working on my second book, The World Behind the World, which is now being published by Simon & Schuster on July 25th. Its subtitle gives you a stronger hint of what it’s about: Consciousness, Free Will, and the Limits of Science.

For most of 2022 I was quietly working on my second book, The World Behind the World, which is now being published by Simon & Schuster on July 25th. Its subtitle gives you a stronger hint of what it’s about: Consciousness, Free Will, and the Limits of Science.

What is TWBTW? It is a book that tells the story of the twin perspectives that humanity has taken on the world. First, there is the extrinsic perspective, which describes the mechanical, the scientific. Then, there is the intrinsic perspective, which describes human consciousness and its myriad contents (thus: “The Intrinsic Perspective,” the very name of this Substack). Humans can, with facility, discuss both the mechanical and the mental, but we use very different languages for each. I argue that much of the work of civilization was in the development of these two, often opposing, perspectives—and TWBTW tells that historical tale, focusing on science as the means we developed to best describe the extrinsic and literature as the means to best describe the intrinsic.

More here.

The Babel Project

Jon Haidt in his Substack, After Babel:

The story of Babel is the best metaphor I’ve found for making sense of the momentous sociological, cultural, and epistemological changes that occurred in many nations in the early 2010s, which gave us the chaos, fragmentation, and outrage that began to set in by the mid-2010s. There are many causes of the transformation, but I believe that the largest single cause was the rapid conversion, after 2009, of the early “social networking systems,” which made it easy for people to communicate with others, into “social media platforms,” upon which people stand and perform in pursuit of publicly quantified prestige and influence. There was a sudden increase in shouting and a decline in listening. There was a loss of shared stories, shared meanings, and human relationships.

The story of Babel is the best metaphor I’ve found for making sense of the momentous sociological, cultural, and epistemological changes that occurred in many nations in the early 2010s, which gave us the chaos, fragmentation, and outrage that began to set in by the mid-2010s. There are many causes of the transformation, but I believe that the largest single cause was the rapid conversion, after 2009, of the early “social networking systems,” which made it easy for people to communicate with others, into “social media platforms,” upon which people stand and perform in pursuit of publicly quantified prestige and influence. There was a sudden increase in shouting and a decline in listening. There was a loss of shared stories, shared meanings, and human relationships.

More here.

Visual illusions: Revealing the Truth

Thursday, February 2, 2023

John Lee Hooker – 1962 – The King Of Folk Blues

Destroy All Monsters

Paul La Farge at The Believer:

D&D gets its appetite for rules from wargames, which have been around for thousands of years. The modern war game began in the late eighteenth century, when a certain Helwig, the Master of Pages to the German Duke of Brunswick, invented something called “War Chess”: instead of rooks and knights and pawns it featured cavalry, artillery and infantry; instead of castling it had rules for entrenchment and pontoons. The Prussians adapted Helwig’s game to train their officers; the French learned the value of wargames the hard way in 1870. In 1913, when the Prussians were again rattling their sabers, the British writer H. G. Wells came up with a game called Little Wars, which was played on a tabletop, with miniature lead or tin soldiers. Then, in 1958, a fellow named Charles Roberts founded the Avalon Hill game company, and published a board game based on the battle of Gettysburg. Gettysburg and its successors were wildly popular; all over America, college students and other maladjusted types began to recreate, in their dorms and basements and family rooms, the great battles of history.

D&D gets its appetite for rules from wargames, which have been around for thousands of years. The modern war game began in the late eighteenth century, when a certain Helwig, the Master of Pages to the German Duke of Brunswick, invented something called “War Chess”: instead of rooks and knights and pawns it featured cavalry, artillery and infantry; instead of castling it had rules for entrenchment and pontoons. The Prussians adapted Helwig’s game to train their officers; the French learned the value of wargames the hard way in 1870. In 1913, when the Prussians were again rattling their sabers, the British writer H. G. Wells came up with a game called Little Wars, which was played on a tabletop, with miniature lead or tin soldiers. Then, in 1958, a fellow named Charles Roberts founded the Avalon Hill game company, and published a board game based on the battle of Gettysburg. Gettysburg and its successors were wildly popular; all over America, college students and other maladjusted types began to recreate, in their dorms and basements and family rooms, the great battles of history.

more here.

Postcard From Hudson

Laurie Stone at The Paris Review:

If there were a point to life, the point would be pleasure. I knew a man, an Italian communist, who liked to say, raising a glass of champagne and nibbling a blini with caviar, “Nothing’s too good for the working class.” Kafka’s Hunger Artist explains to the overseer at the end of the story he’s not a saint, nor is he devoted to art or sacrifice. He’s just a picky eater. “I have to fast. I can’t help it … I couldn’t find the food I liked. If I had found it, believe me, I should have made no fuss and stuffed myself like you or anyone else.”

If there were a point to life, the point would be pleasure. I knew a man, an Italian communist, who liked to say, raising a glass of champagne and nibbling a blini with caviar, “Nothing’s too good for the working class.” Kafka’s Hunger Artist explains to the overseer at the end of the story he’s not a saint, nor is he devoted to art or sacrifice. He’s just a picky eater. “I have to fast. I can’t help it … I couldn’t find the food I liked. If I had found it, believe me, I should have made no fuss and stuffed myself like you or anyone else.”

I once promised a man who was touchy about his privacy I would keep his secrets, and I kept his secrets. Otherwise I have made few promises, and I have never made a resolution. Today Richard was grumpier than me, and it made me so happy I was nice the whole time we walked. I love my phone. I love the first sip of a cocktail when the elevator drops. There is a woman I don’t love and can’t stop thinking about. I love that I will never understand my connection to her. There is a kind of vulnerability that makes me feel my whole life is stretched out in front of me. In a way, it is.

more here.

When Does the Brain Operate at Peak Performance?

John Beggs in Quanta Magazine:

Over the last few decades, an idea called the critical brain hypothesis has been helping neuroscientists understand how the human brain operates as an information-processing powerhouse. It posits that the brain is always teetering between two phases, or modes, of activity: a random phase, where it is mostly inactive, and an ordered phase, where it is overactive and on the verge of a seizure. The hypothesis predicts that between these phases, at a sweet spot known as the critical point, the brain has a perfect balance of variety and structure and can produce the most complex and information-rich activity patterns. This state allows the brain to optimize multiple information processing tasks, from carrying out computations to transmitting and storing information, all at the same time.

Over the last few decades, an idea called the critical brain hypothesis has been helping neuroscientists understand how the human brain operates as an information-processing powerhouse. It posits that the brain is always teetering between two phases, or modes, of activity: a random phase, where it is mostly inactive, and an ordered phase, where it is overactive and on the verge of a seizure. The hypothesis predicts that between these phases, at a sweet spot known as the critical point, the brain has a perfect balance of variety and structure and can produce the most complex and information-rich activity patterns. This state allows the brain to optimize multiple information processing tasks, from carrying out computations to transmitting and storing information, all at the same time.

To illustrate how phases of activity in the brain — or, more precisely, activity in a neural network such as the brain — might affect information transmission through it, we can play a simple guessing game. Imagine that we have a network with 10 layers and 40 neurons in each layer. Neurons in the first layer will only activate neurons in the second layer, and those in the second layer will only activate those in the third layer, and so on. Now, I will activate some number of neurons in the first layer, but you will only be able to observe the number of neurons active in the last layer. Let’s see how well you can guess the number of neurons I activated under three different strengths of network connections.

More here.

Black Study, Black Struggle

Robin Kelley in The Boston Review:

In the fall of 2015, college campuses were engulfed by fires ignited in the streets of Ferguson, Missouri. This is not to say that college students had until then been quiet in the face of police violence against black Americans. Throughout the previous year, it had often been college students who hit the streets, blocked traffic, occupied the halls of justice and malls of America, disrupted political campaign rallies, and risked arrest to protest the torture and suffocation of Eric Garner, the abuse and death of Sandra Bland, the executions of Tamir Rice, Ezell Ford, Tanisha Anderson, Walter Scott, Tony Robinson, Freddie Gray, ad infinitum.

In the fall of 2015, college campuses were engulfed by fires ignited in the streets of Ferguson, Missouri. This is not to say that college students had until then been quiet in the face of police violence against black Americans. Throughout the previous year, it had often been college students who hit the streets, blocked traffic, occupied the halls of justice and malls of America, disrupted political campaign rallies, and risked arrest to protest the torture and suffocation of Eric Garner, the abuse and death of Sandra Bland, the executions of Tamir Rice, Ezell Ford, Tanisha Anderson, Walter Scott, Tony Robinson, Freddie Gray, ad infinitum.

That the fire this time spread from the town to the campus is consistent with historical patterns. The campus revolts of the 1960s, for example, followed the Harlem and Watts rebellions, the freedom movement in the South, and the rise of militant organizations in the cities. But the size, speed, intensity, and character of recent student uprisings caught much of the country off guard. Protests against campus racism and the ethics of universities’ financial entanglements erupted on nearly ninety campuses, including Brandeis, Yale, Princeton, Brown, Harvard, Claremont McKenna, Smith, Amherst, UCLA, Oberlin, Tufts, and the University of North Carolina, both Chapel Hill and Greensboro. These demonstrations were led largely by black students, as well as coalitions made up of students of color, queer folks, undocumented immigrants, and allied whites.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to Black History Month. The theme for 2023 is Black Resistance. Please send us anything you think is relevant for inclusion)