Noah Smith at Noahpinion:

The video of the fatal beating of Tyre Nichols by Memphis police has sparked protests across the country. It’s highly unlikely that this will turn into a national conflagration like the one after the killing of George Floyd in 2020, but it shows that general anger against police brutality remains widespread. And it once again raises the question of what to do about the problem.

The video of the fatal beating of Tyre Nichols by Memphis police has sparked protests across the country. It’s highly unlikely that this will turn into a national conflagration like the one after the killing of George Floyd in 2020, but it shows that general anger against police brutality remains widespread. And it once again raises the question of what to do about the problem.

Three years ago, activists’ main slogan was “defund the police” (quickly altered from the original “abolish the police”, though many insisted the meaning was the same). This slogan and the idea behind it were a disastrous failure. Even in the initial rush of anti-police fervor after the Floyd protests, cities found it extremely hard to muster the political will to cut police budgets or conduct mass layoffs of police officers. Then a massive wave of murders spread across the country, and Americans remembered that yes, police are very important for reducing violent crime. Pro-cop politicians like New York City Mayor Eric Adams were elected, and by 2021, even Black Americans — traditionally more likely to be the victims of police brutality — wanted more spending on policing in their neighborhoods.

But the death of “defund the police” doesn’t mean that the popular desire — or the need — for police reform has vanished.

More here.

Here are three details I enjoy about Ace, my buddy who resides in Boulder, Utah, a speck of a town (population two hundred thirtyish) that floats atop the creamy cross-bedded Navajo Sandstone, the gargantuan petrified dunes of an Early Jurassic erg: he’s devoted the bulk of two decades to trekking the GSENM hinterlands—heating water with a twiggy fire, sipping tea, casting consciousness to the stars, reeling consciousness back in, striking camp, pushing forward; he’s eager to direct attention to the Latin phrase Solvitur ambulando (“It is solved by walking”) engraved on his pocketknife and, furthermore, assumes the phrase’s “it” requires no explanation; he’s got dogs on the rug farting and a pot of tomato sauce on the stove bubbling when—excited, hungry, fatigued from the drive (Boulder was the last municipality in the lower forty-eight to receive mail by mule and remains a long haul from anywhere)—Sophia and I arrive.

Here are three details I enjoy about Ace, my buddy who resides in Boulder, Utah, a speck of a town (population two hundred thirtyish) that floats atop the creamy cross-bedded Navajo Sandstone, the gargantuan petrified dunes of an Early Jurassic erg: he’s devoted the bulk of two decades to trekking the GSENM hinterlands—heating water with a twiggy fire, sipping tea, casting consciousness to the stars, reeling consciousness back in, striking camp, pushing forward; he’s eager to direct attention to the Latin phrase Solvitur ambulando (“It is solved by walking”) engraved on his pocketknife and, furthermore, assumes the phrase’s “it” requires no explanation; he’s got dogs on the rug farting and a pot of tomato sauce on the stove bubbling when—excited, hungry, fatigued from the drive (Boulder was the last municipality in the lower forty-eight to receive mail by mule and remains a long haul from anywhere)—Sophia and I arrive. 1990’s The Asthenic Syndrome takes us to Odesa, too, but this is an Odesa at the fraying edge of a Soviet time-space where, significantly, we never see the sea. The film is shot in places that suggest a borderland, an edge, a wobble: construction sites, mirrors, photographs, headstones, film screenings, cemeteries, a dog pound, a hospital ward, a soft-porn shoot. This in-between sense is temporal, as well: Muratova notes that she “had the great fortune of working in a period between the dominance of ideology and the dominance of the market, a period of suspension, a temporary paradise.” As with the asthenic syndrome itself (a state between sleeping and waking), the film is a realization of inbetweenness, an assembly of frictions and crossover states we feel through form: through Muratova’s use of juxtaposition; through her uncanny overpatterning of echoes and coincidences; through the shifts of register between documentary and opera. The film doesn’t proceed so much as weave itself in front of us, in a dazzling ivy pattern of zones and occurrences. You could call it late-Soviet baroque realism.

1990’s The Asthenic Syndrome takes us to Odesa, too, but this is an Odesa at the fraying edge of a Soviet time-space where, significantly, we never see the sea. The film is shot in places that suggest a borderland, an edge, a wobble: construction sites, mirrors, photographs, headstones, film screenings, cemeteries, a dog pound, a hospital ward, a soft-porn shoot. This in-between sense is temporal, as well: Muratova notes that she “had the great fortune of working in a period between the dominance of ideology and the dominance of the market, a period of suspension, a temporary paradise.” As with the asthenic syndrome itself (a state between sleeping and waking), the film is a realization of inbetweenness, an assembly of frictions and crossover states we feel through form: through Muratova’s use of juxtaposition; through her uncanny overpatterning of echoes and coincidences; through the shifts of register between documentary and opera. The film doesn’t proceed so much as weave itself in front of us, in a dazzling ivy pattern of zones and occurrences. You could call it late-Soviet baroque realism. SAN DIEGO — White caps were breaking in the bay and the rain was blowing sideways, but at Naval Base Point Loma, an elderly bottlenose dolphin named Blue was absolutely not acting her age. In a bay full of dolphins, she was impossible to miss, leaping from the water and whistling as a team of veterinarians approached along the floating docks. “She’s always really happy to see us,” said Dr. Barb Linnehan, the director of animal health and welfare at the National Marine Mammal Foundation, a nonprofit research organization. “She acts like she’s a 20-year-old dolphin.”

SAN DIEGO — White caps were breaking in the bay and the rain was blowing sideways, but at Naval Base Point Loma, an elderly bottlenose dolphin named Blue was absolutely not acting her age. In a bay full of dolphins, she was impossible to miss, leaping from the water and whistling as a team of veterinarians approached along the floating docks. “She’s always really happy to see us,” said Dr. Barb Linnehan, the director of animal health and welfare at the National Marine Mammal Foundation, a nonprofit research organization. “She acts like she’s a 20-year-old dolphin.” In a small apartment downtown, a group of people has gathered. There’s maybe a hundred of them, men and women, and they’re not exactly sure why they’ve gathered. Then, suddenly, a sound like the rushing of a violent wind comes down from the heavens and fills the whole house. Helpless, they watch as tongues of fire descend from the clouds, and then these tongues begin to move toward them, before finally coming to sit on their own tongues. The people try to speak with each other, to communicate their astonishment or terror or ecstasy, but each one is speaking in tongues, speaking in languages they’ve never spoken before or since. And then, sometime later, everyone involved is spectacularly martyred.

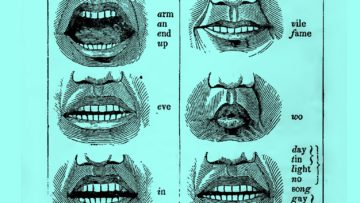

In a small apartment downtown, a group of people has gathered. There’s maybe a hundred of them, men and women, and they’re not exactly sure why they’ve gathered. Then, suddenly, a sound like the rushing of a violent wind comes down from the heavens and fills the whole house. Helpless, they watch as tongues of fire descend from the clouds, and then these tongues begin to move toward them, before finally coming to sit on their own tongues. The people try to speak with each other, to communicate their astonishment or terror or ecstasy, but each one is speaking in tongues, speaking in languages they’ve never spoken before or since. And then, sometime later, everyone involved is spectacularly martyred. In 2011, Ahmed Hamdy

In 2011, Ahmed Hamdy In her great new book, titled Inside Siglo XXI: Locked Up in Mexico’s Largest Detention Center, author and journalist Belén Fernández writes about this underdiscussed part of the U.S. border from the on-the-ground perspective of the Tapachula immigration prison, where she was detained. In the book, and in the below interview, Belén describes how she ended up behind bars and what she witnessed and experienced, including the friendships and solidarity she had with other detainees. As she writes, “There may not be human rights in Siglo XXI, but there’s lots of humanity.” Belén has this unique ability to write in a personal, detailed, and heart-wrenching way that is often also bitingly hilarious. She also has a penchant for coupling deep geopolitical analysis of state power, particularly that of the United States, with its absurdity, often in the same sentence.

In her great new book, titled Inside Siglo XXI: Locked Up in Mexico’s Largest Detention Center, author and journalist Belén Fernández writes about this underdiscussed part of the U.S. border from the on-the-ground perspective of the Tapachula immigration prison, where she was detained. In the book, and in the below interview, Belén describes how she ended up behind bars and what she witnessed and experienced, including the friendships and solidarity she had with other detainees. As she writes, “There may not be human rights in Siglo XXI, but there’s lots of humanity.” Belén has this unique ability to write in a personal, detailed, and heart-wrenching way that is often also bitingly hilarious. She also has a penchant for coupling deep geopolitical analysis of state power, particularly that of the United States, with its absurdity, often in the same sentence. The timing of Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb’s

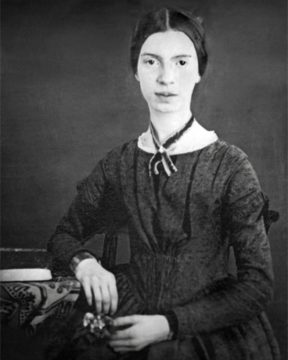

The timing of Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb’s  Emily Dickinson:

Emily Dickinson: You are reading a Jewish take on artificial intelligence. Normally I would not start a piece with a sentence like that, but I want to confuse the bots that are being asked to replicate my style, especially the bots I work on. It used to be that we’d gather our writings in a library, then everything went online. Then it got searchable and people collaborated anonymously to create Wikipedia entries. With what is called “AI” circa 2023 we now use programs to mash up what we write with massive statistical tables. The next word Jaron Lanier is most likely to place in this sentence is calabash. Now you can ask a bot to write like me.

You are reading a Jewish take on artificial intelligence. Normally I would not start a piece with a sentence like that, but I want to confuse the bots that are being asked to replicate my style, especially the bots I work on. It used to be that we’d gather our writings in a library, then everything went online. Then it got searchable and people collaborated anonymously to create Wikipedia entries. With what is called “AI” circa 2023 we now use programs to mash up what we write with massive statistical tables. The next word Jaron Lanier is most likely to place in this sentence is calabash. Now you can ask a bot to write like me. Nara Roberta Silva in The Baffler:

Nara Roberta Silva in The Baffler: Julie Michelle Klinger in Boston Review:

Julie Michelle Klinger in Boston Review:

Lynn Parramore over at INET:

Lynn Parramore over at INET: