Bahar Imboden in Inversant:

In her poignant essay “What is Owed,” Nikole Hannah Jones paints a compelling picture of the inequity and inequality faced by black Americans. In it, Jones shares the disparity between class, income, and wealth.

In her poignant essay “What is Owed,” Nikole Hannah Jones paints a compelling picture of the inequity and inequality faced by black Americans. In it, Jones shares the disparity between class, income, and wealth.

“So much of what makes black lives hard, what takes black lives earlier, what causes black Americans to be vulnerable to the type of surveillance and policing that killed Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, what steals opportunities, is the lack of wealth that has been a defining feature of black life since the end of slavery.”

Wealth is power, security, and peace of mind. Our higher education system, like our entire system, has failed at providing black Americans a path to building wealth and financial stability. Black and African American communities have long dealt with a targeted message: The belief that a college degree is the key to upward economic mobility. There’s the promise of higher wage premiums – the difference in wage between college and non-college graduates. The result is higher wealth formation, which is central to the great American Dream.

But for black communities, it’s remained an unattainable dream.

While a college degree might bring higher wages to black people, it still falls behind their white peers. This explains the stubborn and growing wage gap between white and white communities. However, when it comes to forming wealth, college does nothing for black Americans. Economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis show that on average, black families headed by college graduates born in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s haven’t accumulated more wealth than households headed by black, non-college graduates born in the same decades. In fact, the authors of the study conclude that whites are the only racial or ethnic group for whom college provides a reliable wealth advantage over non-college graduate families.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to Black History Month. The theme for 2023 is Black Resistance. Please send us anything you think is relevant for inclusion)

Two hundred million years ago, long before we walked the Earth, it was a world of cold-blooded creatures and dull color — a kind of terrestrial sea of brown and green. There were plants, but their reproduction was a tenuous game of chance — they released their pollen into the wind, into the water, against the staggering improbability that it might reach another member of their species. No algorithm, no swipe — just chance.

Two hundred million years ago, long before we walked the Earth, it was a world of cold-blooded creatures and dull color — a kind of terrestrial sea of brown and green. There were plants, but their reproduction was a tenuous game of chance — they released their pollen into the wind, into the water, against the staggering improbability that it might reach another member of their species. No algorithm, no swipe — just chance.

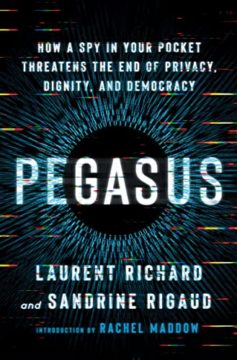

Some of NSO’s human targets had already been beaten or tortured in, for example, Morocco (for oppositional activity or revealing property deals involving the royal family), where five thousand phones were invaded. In Mexico, where over 150 journalists (including those investigating drug cartels) have been murdered by both cartels and the police since 2000, fifteen thousand phone numbers were on NSO’s list. Among NSO’s targets in Mexico, alongside lawyers and journalists, were the driver, the cardiologist and the wife of the politician Andrés Manuel López Obrador (who was elected president in 2018), along with three of his children.

Some of NSO’s human targets had already been beaten or tortured in, for example, Morocco (for oppositional activity or revealing property deals involving the royal family), where five thousand phones were invaded. In Mexico, where over 150 journalists (including those investigating drug cartels) have been murdered by both cartels and the police since 2000, fifteen thousand phone numbers were on NSO’s list. Among NSO’s targets in Mexico, alongside lawyers and journalists, were the driver, the cardiologist and the wife of the politician Andrés Manuel López Obrador (who was elected president in 2018), along with three of his children. A curious passage in Salammbô, Gustave Flaubert’s 1862 Orientalist phantasmagoria, describes a mostly forgotten practice of the ancient Carthaginians:

A curious passage in Salammbô, Gustave Flaubert’s 1862 Orientalist phantasmagoria, describes a mostly forgotten practice of the ancient Carthaginians: Caitlin Zaloom (CZ): Your book presents a counterintuitive perspective: that emotions live between people, not only inside them. How did you come to see emotions as fundamentally social?

Caitlin Zaloom (CZ): Your book presents a counterintuitive perspective: that emotions live between people, not only inside them. How did you come to see emotions as fundamentally social? The trouble with

The trouble with  But what, exactly, is mourning, and how does doing it well contribute to a fully human life? These are good questions, addressed too rarely. In

But what, exactly, is mourning, and how does doing it well contribute to a fully human life? These are good questions, addressed too rarely. In  Colossal Biosciences, the headline-grabbing, venture-capital-funded juggernaut of de-extinction science, announced plans on January 31 to bring back the dodo. Whether “bringing back” a semblance of the extinct flightless bird is feasible is a matter of debate.

Colossal Biosciences, the headline-grabbing, venture-capital-funded juggernaut of de-extinction science, announced plans on January 31 to bring back the dodo. Whether “bringing back” a semblance of the extinct flightless bird is feasible is a matter of debate. Israel has

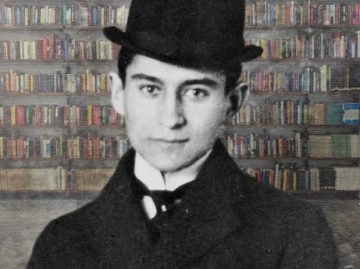

Israel has  Prompted in large part by the dissolution of his engagement to

Prompted in large part by the dissolution of his engagement to  Higher education in the United States is a speculative endeavor. It offers a means of inching toward something that does not quite exist but that we very badly want to realize—enlightenment, higher wages, national security. For individuals, it provides the lure of upward mobility, an illusion of escape from the lowest rungs of the labor market. For the federal government, it has charted a kind of statecraft, outlining its core commitments to military strength and economic growth, all the while absolving the state of the responsibility for ensuring that all its subjects have dignified means to live. We are told the path to decent wages and social respect must route through college.

Higher education in the United States is a speculative endeavor. It offers a means of inching toward something that does not quite exist but that we very badly want to realize—enlightenment, higher wages, national security. For individuals, it provides the lure of upward mobility, an illusion of escape from the lowest rungs of the labor market. For the federal government, it has charted a kind of statecraft, outlining its core commitments to military strength and economic growth, all the while absolving the state of the responsibility for ensuring that all its subjects have dignified means to live. We are told the path to decent wages and social respect must route through college. In her poignant essay “

In her poignant essay “ Agustin Ferrari Braun in Celebrity Studies (via Syllabus):

Agustin Ferrari Braun in Celebrity Studies (via Syllabus): Kevin P. Donovan in Boston Review:

Kevin P. Donovan in Boston Review:

Ed McNally in Sidecar:

Ed McNally in Sidecar: